The first subperiod that was identified by Dr. David Anderson in his work for the New Georgia Encyclopedia and edited by Chris Dobbs was the Early Paleoindian period. This period was characterized by small, triangular pre-Clovis points and Clovis-like fluted stone points. It is believed that the distribution of these points throughout all the environmental zones in the Southeast represents the initial exploration and colonization of the region. Stone tools and debitage were traded or transported over hundreds of kilometers from their quarry source suggest that there was great mobility among the bands of Early Paleoindian people.

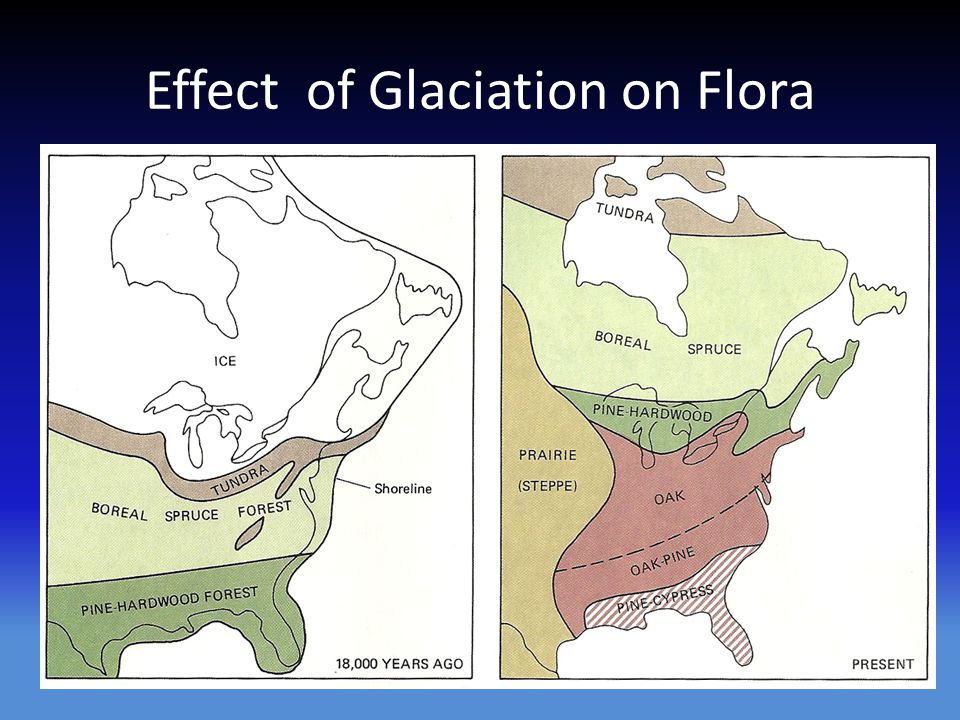

The Southeast, at this time, consisted of three broad environmental zones. The most northern climate was the boreal forests that were limited to the high elevation of the mountainous regions of Tennessee and North Carolina (Map 1B). These forests consisted of vegetation that was primarily cone-bearing, needle-leaved, an/or scale-leaved evergreen trees that thrived in cool areas with long winters and moderate to high annual precipitation. These forests are now limited to the northern areas of Canada, Alaska and Russia. Most of the Southeast was covered with temperate oak-hickory-pine forests much as they are today. Subtropical sandy scrub areas, the most southern area, was confined to the Florida peninsula and the coastal plain, which extended several kilometers outward from its present location due to the lower sea level. Megafauna of the Late Pleistocene were found in all three of these environmental zones.

The late glacial southeastern environment encountered by these first people was markedly different from today’s environment. Sea levels were more than 200 feet lower than present levels, and the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico shorelines were 100 or more miles seaward of their present locations. Global temperature was rising rapidly during the interval from 15,000 to 11,000 years ago, albeit with occasional sharp reversals, and the great continental ice sheets were retreating, causing the coastline to move rapidly inland.

Stone projectile points and tools offer us only a limited understanding of the camp site life during the Paleoindian period. Evidence of other sites from this period in both North and South America give us a glimpse of life as it must have been lived during the Early Paleoindian period. These sites also show us other, more perishable tool resources that might also have been used at sites within the southeastern United States.

The Cactus Hill site is perhaps one of the earliest sites in the eastern United States. The site excavation was a salvage project that began in 1993. The project was directed by John McAvoy and accomplished with the help of an all volunteer group. The Cactus Hill site was named after the prickly pear cactus that covers it. This is a culturally stratified archaeological site located on the Nottoway River in Sussex County, near the town of Stony Creek, in eastern Virginia. Evidence indicating a Clovis and pre-Clovis occupation of the site are the most important discoveries at Cactus Hill. A date of 18,000 years BP was derived using Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) on the soil in which two points, believed to be pre-Clovis, rested.

A second site from the Early Paleoindian period is the Monte Verde site. From 1977 to 1985, Tom Dillehay of the University of Kentucky excavated at Monte Verde, some 31 miles (50 km) inland from the Pacific Ocean in southern Chile. The early dating at Monte Verde adds to evidence showing that the human settlement of the Americas pre-dates the Clovis culture at the site by roughly 1000 years. The Monte Verde site has two distinct levels. The upper level, MV-II, has been extensively characterized. Its occupation is reliably dated to 14,800 – 13,800 BP. The lower level, MV-I, is less well understood. This contradicts the previously accepted “Clovis first” model which holds that settlement of the Americas began after 13,500 BP. The Monte Verde findings were initially dismissed by most of the scientific community, but in recent years the evidence has become more widely accepted in some archaeological circles, although vocal “Clovis First” advocates remain.

The water-saturated deposits of the Monte Verde site, on Chile’s Chinchihuapi Creek, afforded excellent preservation of organic remains in what was interpreted as a habitation surface, designated MV-II. It was a small camp used by 20 to 30 people. Radiocarbon dates from that level averaged ~12,500 years ago, thus reflecting some of the possible lifeways of the Early Paleoindian period. Among the features recorded by the excavators were two large and many small hearths and 12 huts about ten by 11.5 feet (3 by 3.5 m). Most of the stone tools found at the site were made of local raw material and consist of cobbles with a few flakes removed to make simple but functional working edges. There were two bifacially flaked points. Worked wood ranging in size from logs to branches, was also found. Bones, ivory, and possible tissue from mastodons were found along with remains of Pleistocene llamas, small mammals, fish, and mollusks. The remains of plants from various areas such as coastal areas or the mountainous Andean region of northern South America, or from arid grassland habitats were also recovered. The imprint of a human foot in clay was among the most intriguing finds from the site.

A recent return to the Old Vero site (8IR009) in Vero Beach, Florida where the Ice Age “Vero Man,” one of the oldest collections of human remains ever discovered in the New World was recovered by Florida State geologist Elias H Sellards in 1915. The research of Drs. Adovasico and Hemmings at the site in 2015 recovered preserved cordage which dates from at least 9,000 CALYBP – a rare discovery indeed in Florida’s climate. Since then a number of plant fiber-derived artifacts have been recovered. These same kinds of articles may have been used at sites in central Georgia, but were lost to decay over the millennia.

A third significant site of this period is the Gault site in Williamson Countysouth central Texas. Gault is a large site, estimated to be a half mile by a little over a tenth of a mile wide. It is classified as a stone tool manufacturing and habitation site. With abundant archaeological evidence for human occupations spanning the entire local prehistoric record of 11,000 RCYA. It occupies the constricted head of the valley with a small stream of reliable springs flow and abundant chert of extraordinary quality crops out. Today the locality is well watered and supports a diverse array of trees and other vegetation on deep soils in stark contrast to the sparse vegetation on thin, rocky soils of the immediately surrounding uplands. At a larger scale, this setting is in the Balcones Ecotone (a transitional zone between two distinct habitats) where resources of limestone uplands mingle with contrasting landscapes occurring on the adjacent coastal plains. The Edward’s Plateau differs in its geology, soils, flora, and fauna from the Black Prairie region of the Gulf Coastal Plains.

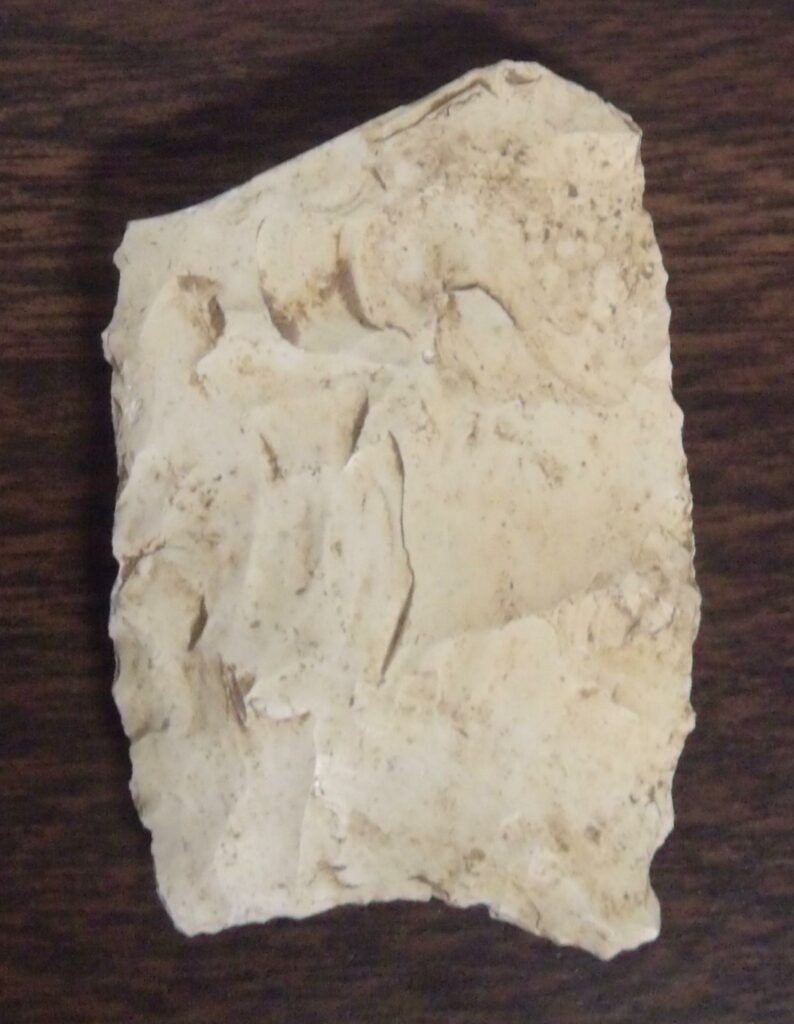

This engraved stone was found at a depth of about 3.5 feet (106.7 cm) on the Gault site by David Olmstead. A complete and undamaged Clovis point was also found nearby. This engraved stone has been referred to as the “Wheatstone” because the design seems to illustrate growing plants. Both sides are engraved with five to eight vertical lines that extend upward from a horizontal line. Each vertical line was then engraved with a diamond on the end. Some of the diamonds are filled with vertical parallel lines. This engraved stone measures 4 1/16 inches (10.2 cm) long, 2 5/8 inches (6.6 cm) wide and 5/16 on an inch (7 mm) thick.

The Gault site produced Clovis points, point preforms, tools made from blades, cores, burins and small engraved stones (above). Excavations between 1998 and 2002 by archaeologists from the Texas Archaeological Research Laboratory at the University of Texas at Austin recovered approximately 800,000 artifacts from the site. One of the most important artifact types to have been recovered from the Gault site is engraved stones. By 2001 at least 30 engraved stones had been found. Their direct association within the Clovis horizon at Gault is a significant discovery. Engraved stones from this early period in North America are almost unknown. In 2002 there was an important discovery of a 6 by 6 foot pavement of gravel that has been interpreted as evidence for one of the earliest man-made structures found in North America.

The sites containing pre-Clovis materials are extremely scarce in the Western Hemisphere, yet we have already discussed a few of them. If the dates from these sites are accurate, the peopling of the Americas began some 18,000 years BP. Along with the human presence in North America came their tools and other elements of their way of life. Pre-Clovis blade forms have come from at least three locations, the oldest of which is the Cactus Hill site discussed above (left). The second site, in terms of age, to produce a pre-Clovis blade was the Meadowcroft Rockshelter site near Avella, Pennsylvania. The Meadowcroft site is unique in that it has been continuously inhabited for the past 19,000 years! The pre-Clovis blade recovered from the site is believed to date from 16,000 years BP (center). The third pre-Clovis blade is from Florida’s Aucilla River (right). The blade was recovered from the Page/Ladson site and is believed to date to 15,405 years BP.

A similar description to that used by McAvoy (1997) might be used to describe each of these blades as all three blades are thin and relatively flat in cross-section. They have flat to concave basal edges that have been thinned by removing small to medium thinning flakes by pressure flaking. The Cactus Hill point has been heavily resharpened into a pentagonal shape, but without the excessive ware might otherwise have looked similar to the Meadowcroft blade (center) or the Page/Ladson blade (right). The Cactus Hill blade measured 1 3/8 inches (3.5 cm) long. The other examples are slightly larger.

The Clovis point was named from examples found associated with extinct animal remains near Clovis, New Mexico.[i] The type is a medium to large sized lanceolate point measuring 1.5 to more than 5 inches in length with an average length of between 3 and 4 inches. Clovis points are usually developed from fairly thick preforms. This develops a lenticular to flattened cross section above the fluted hafting area. Fluting results from removing one or more flakes from a prepared striking platform at the basal edge. The flute, when present, usually extends to no more than half of the blade length, but may occasionally extend much further.

The sides of the hafting area and basal edge are ground smooth. This may have accommodated the hafting process by preventing the sharp edges of the blade from cutting the strands of sinew used to bind the point to the foreshaft. The parallel sides of the hafting area of the Clovis point are important in distinguishing it from the more waisted Simpson point. The basal edge is concave with pointed to rounded corners that may flare out slightly. This treatment distinguishes the Clovis from the rounded ear of the Suwannee point or the auricle of the Simpson point. The unfluted Clovis (Figure 1.2b) shares these same characteristics; however, fluting has been replaced with the removal of several basal thinning flakes to accommodate hafting.

A fluted Clovis point found at the Macon Plateau in Georgia in 1935 was one of the first Paleoindian points unearthed in eastern North America in stratigraphic context. The artifacts were heavily weathered, a condition considered to be a good indicator of an early site in Georgia. Only one fluted point was found at the Macon Plateau, in spite of a massive excavation effort, and to date no site professionally excavated in the state has ever produced more than one fluted point in good context. James Dunbar and Ben Waller did extensive Paleoindian research in Florida’s rivers and have suggested an early date of 11,300 BP for Clovis occupation.[ii] Because Clovis points are rare and because of the generally mixed context of the riverbeds where most of the examples have been recovered, well documented, datable finds are difficult to acquire.

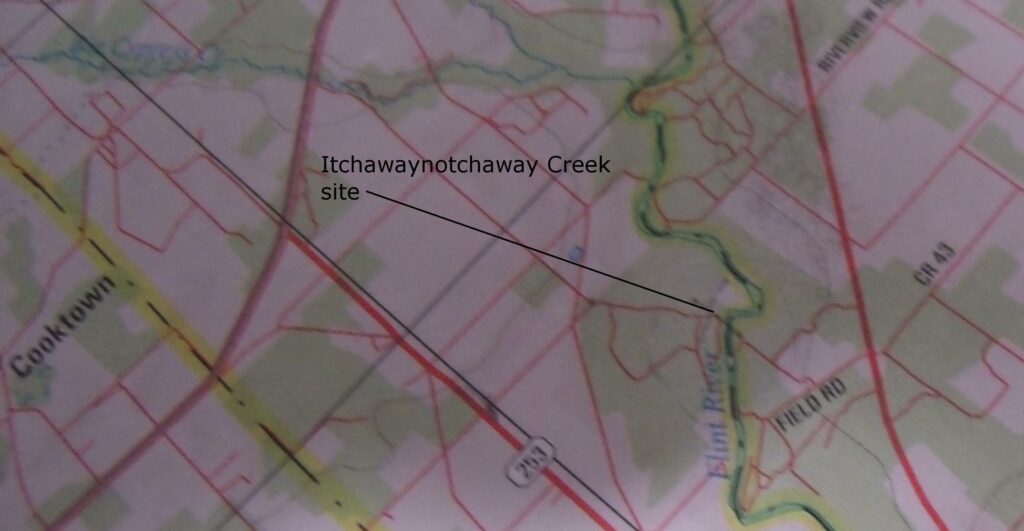

The vast majority of Paleoindian points have been recovered from or near rivers in Georgia as shown on Map 1C. Several hundred Paleoindian points, including the Clovis type, have been recovered from a two-mile stretch of the Santa Fe River and over fifty were found in the Oklawaha River in Florida. Other finds have occurred in the Wacissa, Aucilla, and Waccasassa rivers.

The information for Clovis distribution that is illustrated on Map 1C was approximated from the survey of points as recorded by the Society for Georgia Archaeology records done by Jerald Ledbetter in 2016. Note the absence of recorded points in the counties of north-central and coastal Georgia and the clusters of points recorded on or near Georgia’s Fall Line. This corresponds to and may be an indication of a preference of these early cultures for the pine and hardwood forest ecosystem of Georgia over the boreal spruce forests further north. This shift in presence may indicate the movement of game along the rivers of south-central Georgia.

Tools from this period can be both specific to the Paleoindian period and shared with other subsequent cultures across the millennia of time. Tools that were present in the Early Paleoindian period include perforators, various kinds of scrapers, prismatic blades, flaked knives, utilized flakes, spokeshaves, gravers, abraders and choppers. Some of the tools more specifically used during the Early Paleoindian period that did not seem to be more heavily used during later periods were prismatic blades, burins and unifacially flaked knives. A new archaeological find suggests that humans inhabited America, specifically parts of what is known today as Texas, as far back as 21,700 years ago. A group of scientists led by Thomas Williams of Texas State University recently unearthed more than 150,000 human-modified stones at the Gault Archaeological Site in Central Texas, about 40 miles north of Austin. The group doesn’t claim to have nailed the answer to the question, “Who were the first Americans?” but they might have discovered another runner in that race. The find illustrates “the presence of a previously unknown projectile point technology in North America from before [16,000 years ago],” say their findings, published in the July 11 edition of the journal “Science Advances.” Williams’ team of archaeologists excavated the Texas bedrock and uncovered ancient rocks shaped into bifaces — used as hand axes — blades, projectile points, engraving tools and scrapers dating to between 16,700 and 21,700 years. They refer to the tools as the Gault Assemblage.

The prismatic Blades illustrated above are from the University of Georgia collections and the Topper, Pre-Clovis site.

The use of the “Prismatic Blade” name seems to belong to Bennie C. Keel from his work at the Garden Creek site where he recovered 79 examples. Keel described these blades as generally parallel-sided with one or more medial ridges on the dorsal surface. A well defined striking platform or bulb of percussion is present on at least half of the examples. Striking platforms showed slight grinding in only a few cases indicating that cores were not often ground, but rather natural plains were used to strike flakes. The mid sections of the blades showed the typical ridged backs and parallel sides. The terminal ends were rounded and many had cortex on the ends. A few examples had a single ridge on the dorsal surface, but most had two or more ridges.

The definition given by Jerald Ledbetter (1995) for “blade-like flakes” seems to include these blades along with other similar long reduction flakes. Ledbetter’s definition gives a rule of thumb that the length of the blade is at least twice as long as its width. He describes them as long, narrow, thin flakes characterized by the presence of a dorsal ridge parallel to the long axes of the flake. Keel also mentions the presence of use ware along the edges, a characteristic that he mentions as not being present on the examples he recovered at the Garden Creek Mound 2 site. Keel’s examples from the Garden Creek Mound 2 site dated between 200 and 400 A.D., but this seems to represent only the very recent usage of this tool form. Many of the examples shown above are much older and come from the Clovis and pre-Clovis layers of the Topper, Cactus Hill, and Gault sites.

The examples recovered by Ledbetter from the Mill Branch site 9WR4 were made of chert while those from 9WR11 were made from local blue-green quartzite. The Mill Branch site examples suggest a Late Archaic context. Joseph McAvoy (1997) also mentions the presence of “edge worked and edge used flakes” below Clovis points at the Cactus Hill site in Sussex County, Virginia.

The above illustrated bruins are courtesy of Mr. Gary Davis and other private collections.

Burin is a French word that means “cold chisel.” It is a specialized type of lithic flake or, in the case of the example on the upper left, a broken point reshaped into a tool. These flakes are heavily bodied and have a chisel-like edge that was probably also used for engraving or carving wood or bone. More recently, these blades have been identified as chisels with the addition of various diagnostic descriptive terms attached. Not all of these tools are unifacial, although many are.

Because this tool type lacks any indication of pressure flaking or resharpening or any identifiable type of reproduced form such as hafting, very few bruins have been reported in published reports. In his comments on the lithic assemblage of the Graham Creek East site (9GO32) and the lithic technology, typology, and chronology of the Thomas collection from that site, Scott Jones[iii] stated that, “Lithic technology for this time period (and indeed, all of prehistory) should be viewed as implicitly fluid. This should be especially true for Paleoindian assemblages, in consideration of the logistical planning they display. Well-thinned and/or fluted preforms serve as knives and other multipurpose tools. Finished points, when broken, are recycled/reused/re-based/re-tipped according to need; biface fragments are used for scrapers, burins, bipolar cores, and wedges.”

The examples above are all from the Central Georgia Surface Survey.

Flake knives are expedient tools that are made at the site of use and may be discarded or reused as the need dictates. These knives are more than the small flaked knives discussed below, but are made from large percussion flakes and are then pressure flaked on all sides and both faces, but remain essentially unifacial. The bases of the examples observed from Briar creek all have rounded bases and may have been hafted. They do not assume any recognizable blade form that is readily identifiable by their diagnostic traits like the Stanfield Knife, but are very similar in many respects. These have been referred to as “Paleo Unifaced Blades,” but their duration of use extends beyond the Paleoindian period. David DeJarnette, Edward Kurjack, and James Cambron (1962) listed these blades as “bifacial chipped tools” at the Stanfield-Worley Bluff Shelter, describing them in much this same way.

A series of 32 of these blades were recovered at the Briar Creek site. That site contained predominately (158) Middle and Late Archaic diagnostic point types and only three Dalton points. It is difficult to tell from a surface collection precisely where these knives fit culturally, but a comparison of traits seem to associate them within the Late Archaic period. Many examples of these points have been recovered by artifact enthusiasts across the Southeast from Florida, Georgia, and Alabama, many in a contest that suggests a Paleoindian origin including several examples from the Nuckolls site in Tennessee. At that site the blades take on a more triangular shape, but with carefully flaked edges and a triangular distal end[iv].

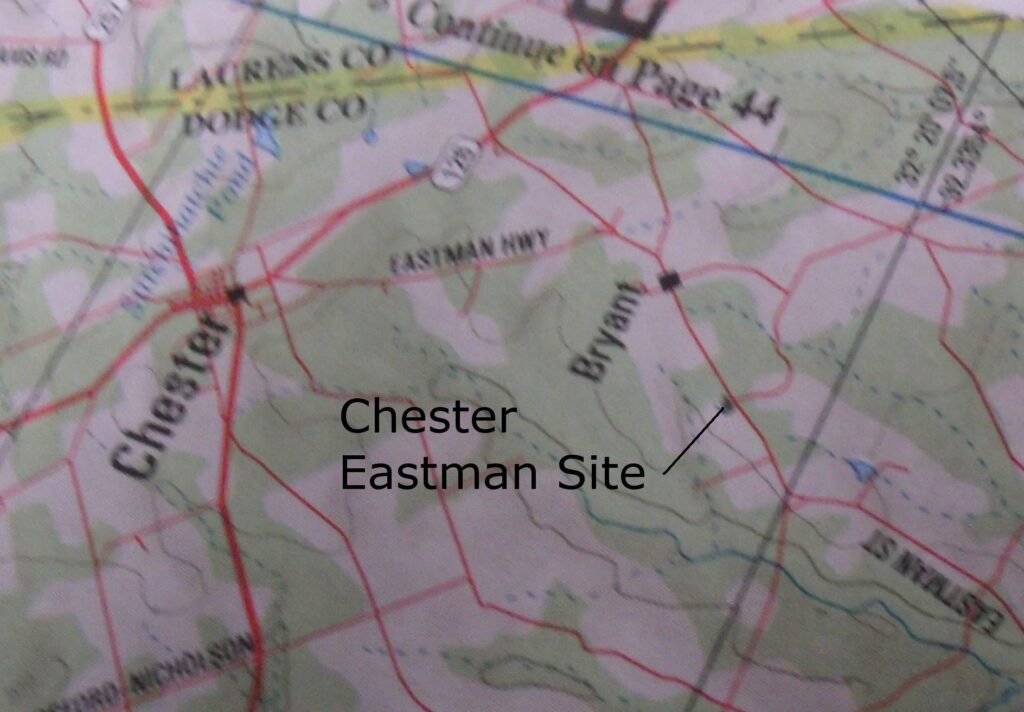

Of the 172 sites surveyed by Mr. Perry, eleven of them contained Clovis-like projectile points that belong to the Early Paleoindian period. Those eleven sites occur in seven different counties, Dooley, Washington, Jefferson, Laurens, Glasscock, Wilkerson and Baker. The ten sites containing Clovis points that were recovered by Mr. Perry are all listed below with descriptions of the sites and comments on the points recovered.

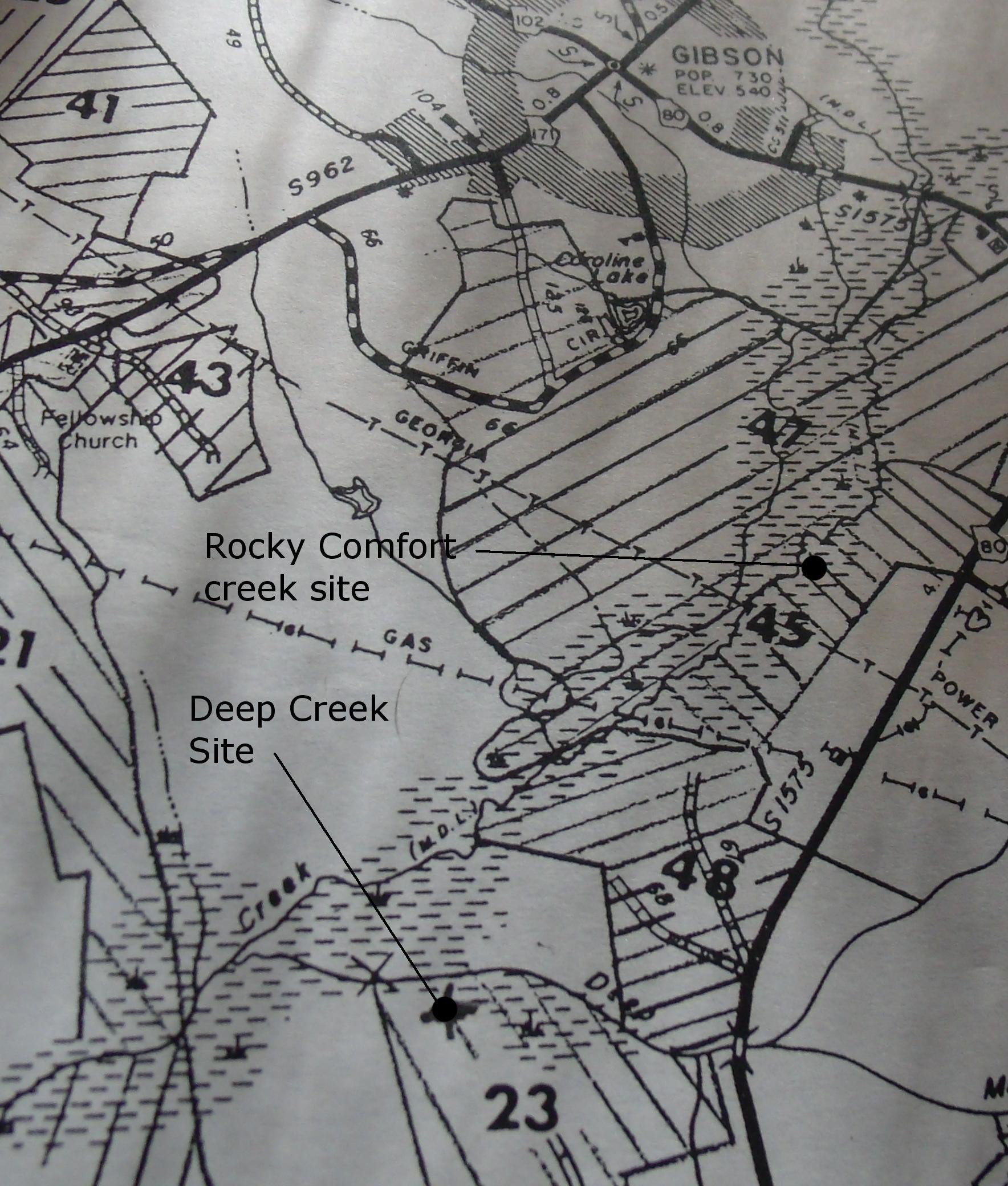

The Deep Creek site was located south and east of the town of Gibson on Deep Creek just east of its juncture with Rocky Comfort Creek. The site was located on the southern edge of some clear-cutting activity. The resulting field had been cleared and plowed in preparation for planting pines. Mr. Perry’s work was primarily carried out just outside the tree line along the creek, but also extended into the field for a short distance in an area where site debris could be seen.

Among the 2,224 artifacts recovered from the site by Mr. Perry was a single Clovis-like point. The point measured only 38mm in length and 18mm in width. It was not fluted and appeared to have been made on a flake blank of local Coastal Plains chert. Its identification as a Clovis type has been authenticated by Mr. Jerald Ledbetter. The apparent resharpening at the distal end and the small size suggest that it had served as a cutting tool.

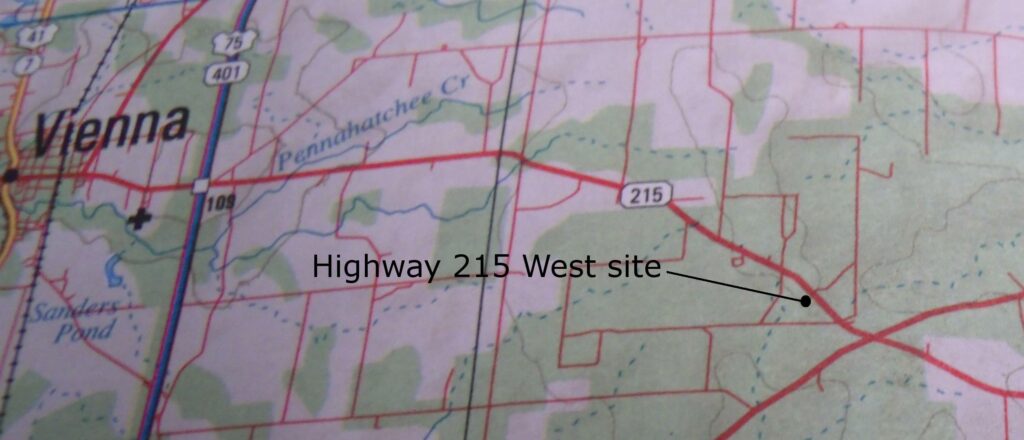

The Highway 215 site in Dooly County is located about 1.5 miles west of the intersection of highway 215 and highway 257 in the southeastern corner of the county. The area is characterized by upland resources and is further away from creeks and rivers than one might expect. The Gum Creek that runs near Cordele, Georgia, one of the nearest waterways, is some 30 miles away.

The site yielded a total of 114 artifacts. Most of the artifacts from the site were projectile points that widely distributed among various archaeological periods, but it contained two Clovis points from the Early Paleoindian period and a Simpson Base from the Middle Paleoindian period. Finally, the Late Paleoindian period seems to have seen some increased campsite activity with several Dalton points and associated tools present at the site.

The site is especially interesting because it is one of two sites to yield two Clovis points. Point A is 3cm long (to break) and 2.75cm wide. This example was made from Coastal Plains chert. Point B is 6cm long and 2.75cm wide. This point was made of Daltonite.

Point A is made of Coastal Plains Chert, Point B may be made of Little River metadacite, Point C and D are also made of Coastal Plains chert.

The Sun Hill Creek site is located on the Anderson family farm in a plowed field along Sun Hill Creek and just west of highway 242 in Washington County, Georgia. The site is on a plot of high ground at the juncture of the creek and one of its tributaries. When Mr. Perry arrived, the field had been plowed including a small knoll about three feet in height, possibly a small mound that was located about 50 feet from the banks of Sun Hill Creek.

The site yielded a total of only 107 artifacts and might not have been seen as significant enough to warrant a report except that it contained a fluted Clovis-like point (left), the base of a Suwannee-like point (center), and two Simpson-like point bases (right), and a whole Suwannee point (illustrated with the Middle Paleoindian period), all belonging to the Middle Paleoindian period. The site also contained a few Late Paleoindian Dalton points, but very few tools that could be clearly associated with these early inhabitants.

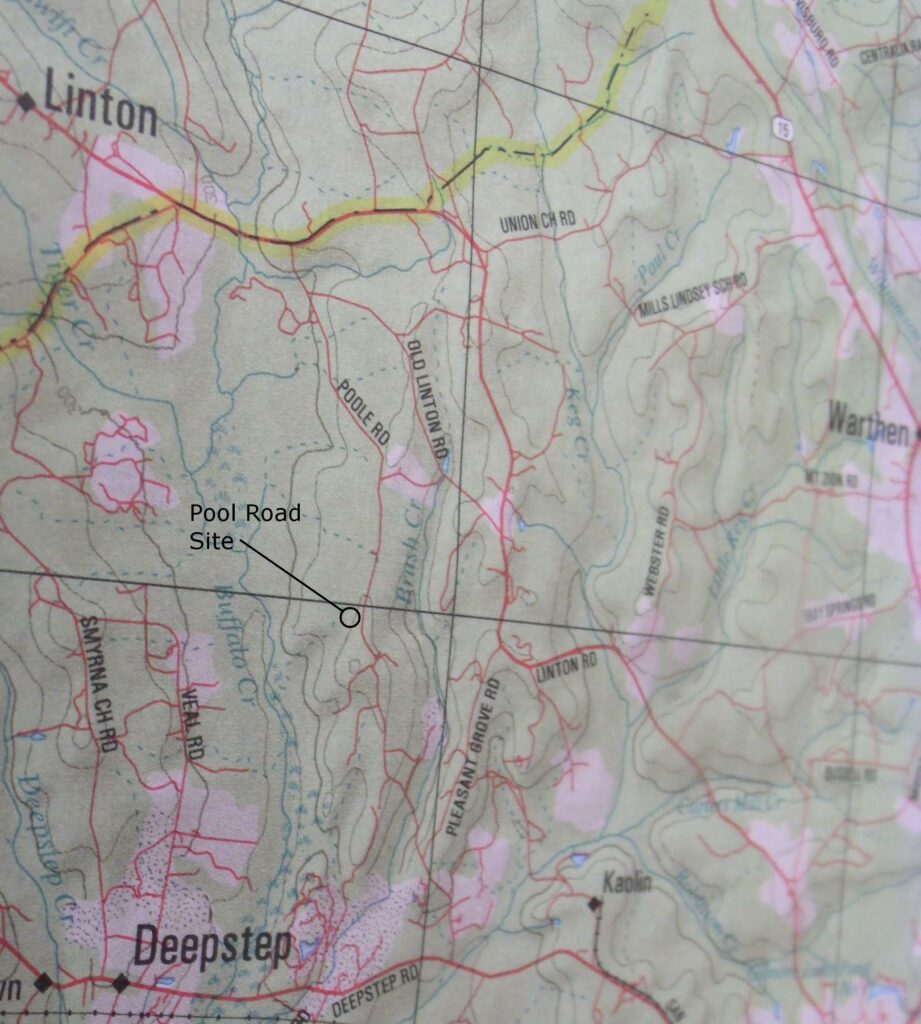

The Pool Road site lies in the northwest section of Washington County. Pool Road runs from the town of Linton in Hancock County to the town of Deepstep in Washington County. The road runs to the west of Brush Creek and to the east of Buffalo Creek and nearly parallel to both streams for most of its length. The site was located in a field that lay close to Buffalo Creek that had been clear-cut and was being prepared for planting pine trees. The hilly terrain in the area was used by the people of the period to provide high ground to establish their campsite.

The illustrated photo is both sides A and B of a Clovis point from the site possibly made from hornfels “457 material.” The point measured 1.75 inches long and about .75 inches wide. It was not fluted on either side and the reverse side had a knot of material that the knapper had been unable to remove. The lateral and basal edges had been ground smooth.

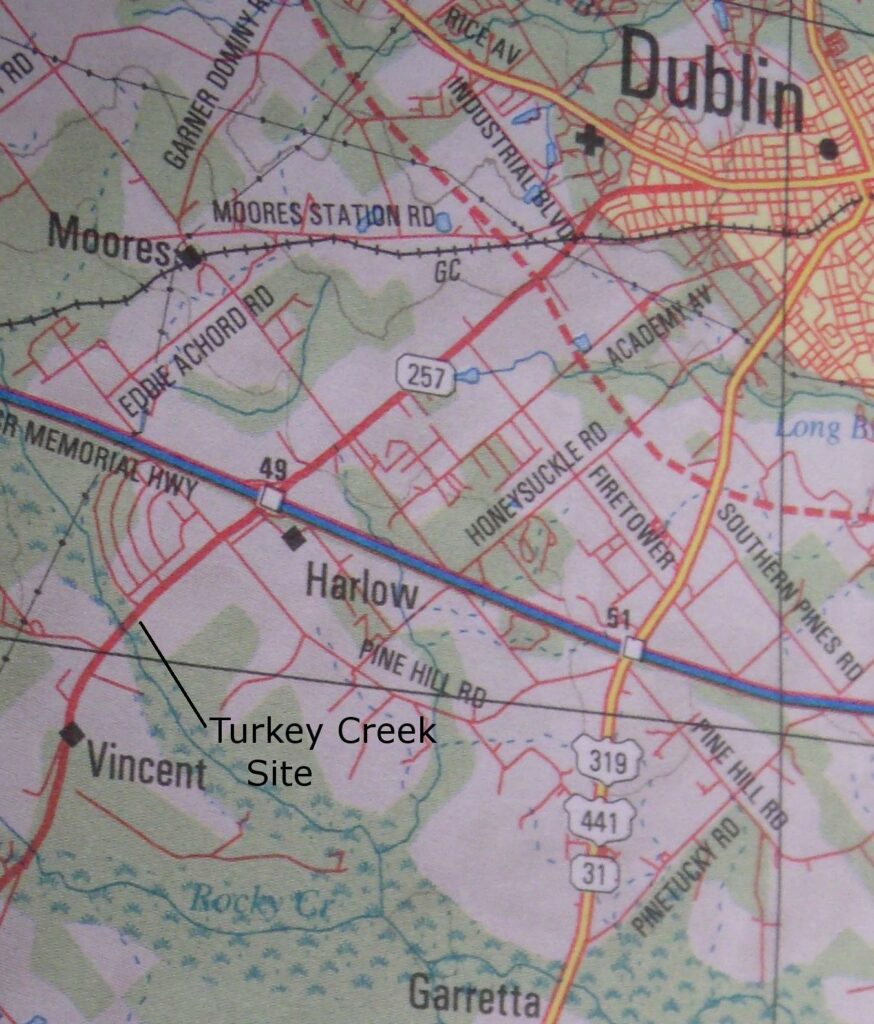

The Turkey Creek site is located just off from Highway 257 and south of Interstate 16 in Laurens County. The site is near the town of Vincent on the south side of Turkey Creek. Turkey Creek is a rather large stream that runs diagonally from Dublin, Georgia southeast to Palm Lake where it converges with the Oconee River.

The site contained only 67 artifacts, one of which was a Clovis point belonging to the Early Paleoindian period. The site also contained a Late Paleoindian Dalton point. The Clovis point was made of Coastal Plains chert and was broken at a little more than the midpoint. The remaining portion of the point measured about 2 inches in length and about 1.5 inches in width. The point was not fluted and some typical overshot flaking was visible.

The site yielded very few artifacts, but did include an unfluted Clovis point. The point was made of Coastal Plains chert. It measured 2.25 inches long and 1.25 inches wide. The basal edge had been smoothed and a wide thinning flake, but not a flute, had been removed from the central portion of the blade.

Point A is the base of a fluted Clovis made of Coastal Plains chert. The fragment is only about .5 inches long and about 1 inch wide. Point B is another Clovis base with a short flute that is also made from Coastal Plains chert. This example measures 1.25 inches long and about 1 inch wide.

The Briar Creek site in Burke County was an open field that had recently been clear-cut of trees and appeared to have been prepared for planting additional trees. Artifact hunters had already been investigating the site and lithic debris was scattered across the area.

Even though others had already searched the site and Mr. Perry’s investigation was little more than a salvage surface collection, the site produced 475 artifacts including two Clovis base fragments. Other point types from the Paleoindian period included three Dalton points from the Late Paleoindian period.

The two Clovis bases were made of Coastal Plains chert that may have been mined just a few miles away in an ancient quarry site located along Givens Church Road that runs along Briar Creek in Burke County. Point A (left) measures 1 inch wide and 1.5 inches long. Point B (right) measures about 1.2 inches wide and 1.6 inches long. Neither point was fluted, but both had been basaily thinned.

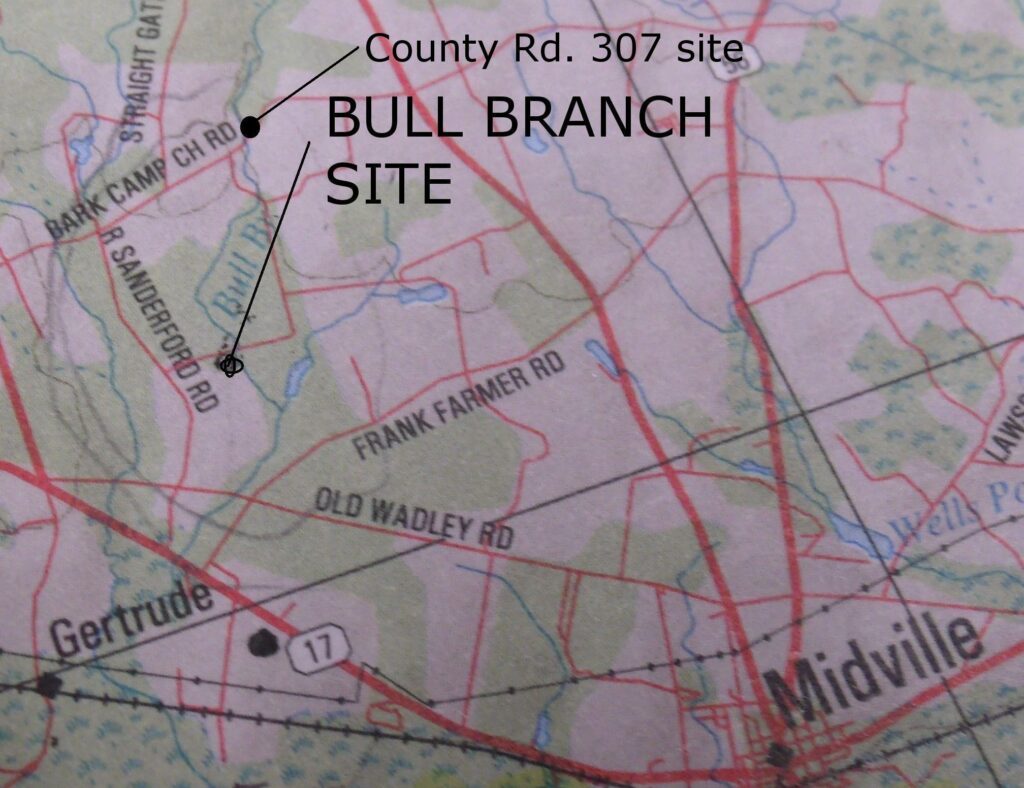

The Bull Branch site was a plowed field when Mr. Perry arrived there. The site is located near the bridge that crosses Bull Branch Creek just off Sanderford Road in Burke County. The site only contained 29 recorded artifacts. Among them was a fluted Clovis base, a Kirk Corner Notched point, a Hendrix Scraper and a Screven Scraper of a much later period. Even the Hendrix Scraper may not have been associated with the Paleoindian period. The site also produced two Dalton points from the Late Paleoindian period.

The fluted Clovis base pictured below measures about 1 inch wide and about 1.25 inches long. It is made of Coastal Plains chert. The point fragment appears to have contained the entire length of the flute. Both basal and lateral grinding is present along the edges of the basal fragment.

[i] Wormington, H.M., Ancient Man In North America, Denver Museum of Natural History Popular Series No.4, 1957

[ii] Dunbar, James and Benjamin I. Waller, Distribution of Paleo-Indian Projectiles in Florida, Florida Anthropologist, Vol. 30:2, 1977

[iii] Jones, Scott, Jerald Ledbetter, and Lee Thomas

2014 An Inventory of Bifaces and Other Formal Tools from the Paleoindian Occupation Locus on 9GO32, The Graham Creek East Site, Lee Thomas Collection

[iv] Hothem, Lar

1986 Collecting Indian Knives