There are a variety of bone tools that come from archaeological sites. Unfortunately many of them look very similar and are even made from the same bones of animals. We have separated the tool types for quick identification, yet placed them in the same article so you can see their differences in comparison.

Bone artifact were fire hardened and have been found in storage pits packed in ash. When they are recovered, the ash is as dry as the day it was taken from the fire. Bone artifact left to the elements often remain, even after thousands of years, because of this treatment. For stronger tools and heavier work, Antler was often the material of choice because of its hardness and durability.

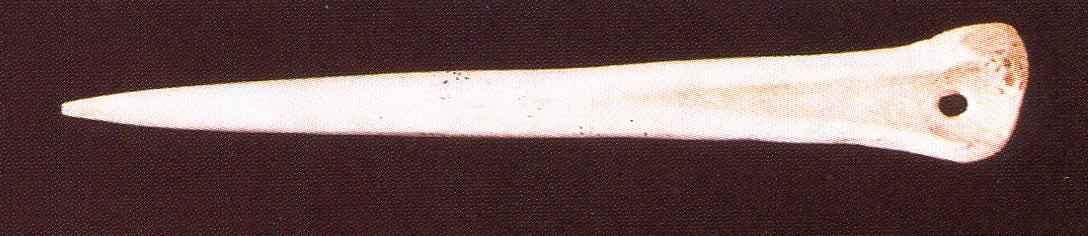

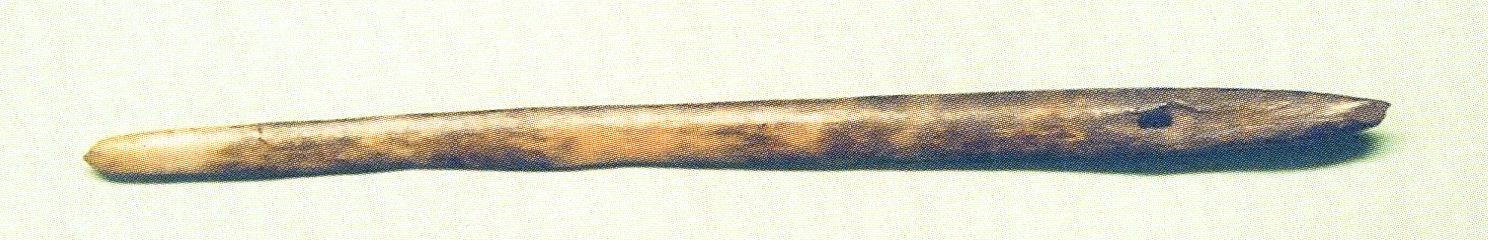

Needles were made from a variety of different bones. Some had natural openings like the catfish spines pictured above while others had holes bored in them. The needle is small and narrow with a very fine point in comparison to the shuttle used in weaving. Needles average 2 to 3 inches in length. A weaving shuttle is considerably larger and longer. Bone needles are said to have been used as early as the Paleoindian period as evidenced by this example from Texas.

If awls are one of the most numerous bone artifacts in archaeological sites, weaving shuttles are one of the least common bone implements recovered in sites. Shuttles are larger and longer than most needles averaging in length between 3 and 5 inches. The pointed end of the shuttle is often narrowed to a rounded point rather than sharply pointed. This would allow the shuttle to slide back and forth between the strands of the weave without puncturing and dividing the strands. The shuttle’s hole would also be larger to accommodate the woven strand rather than the thin strands of sinew that might be used in sewing. Not all shuttles have holes. Some examples have notches either in the sides or in the large end where a hole might otherwise be. Like needles, the shuttle would be highly polished to make it slide between the strands of the weave. The art of weaving dates to at least the Middle Archaic (7400 B.P.) at the Windover site in Brevard County, Florida, where many different patterns of weave were recovered having been preserved in muck. Because of their similar size and length, care should be taken to identify the rare shuttle from the more common hair pin, which is usually engraved. Bone hair pins appear under the Beads and Decorative section of this site.

Fish hooks are one of the most desirable and collected of all bone artifacts. Hooks come in a variety of single and multiple bone designs. The most common fish hood is designed from a single bone of the white tail deer. The foreleg bone has a natural groove along its length. Incising the bone with a graver down the bone opposite the natural groove allowed the bone to be split in half. One or more hooks could then be carved from each bone as shown above. The long bone has a natural grain that causes the hooks to break at the lower portion of the curve. For this reason this portion of the hook is much wider than the shaft or point of the hook. (This weakness may have made hooks constructed from cut deer toe bone more desirable to some.) This type of fish hook is generally attributed to the Mississippian period. The presence of fish hooks indicates hand-line fishing, which was probably more common that we realize. Fish hooks were also made of shell, espe4ially along the coastal areas. Flint fish hooks can be seen in many collections, but there are no known recoveries from archaeological sites. The flint fish hook has been a popular “fake” since 1890.

Both of these chisels are made of more durable antler rather than bone as bone has a linear grain that might break under the heavy pressure of chisel work. The bit end should show wear and polish and the butt end may show signs of fracturing from hammering, although a mallet was probably used to avoid excessive damage.

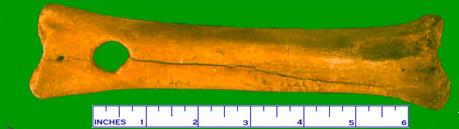

The bone shaft wrench is common tool found in many western sites. The shaft wrench is believed to have been used for straightening arrows in which the wood of the shaft was heated. The shaft wrench was used to hold the hot arrow shaft while pressure was applied to straighten the shaft. The arrow shaft would be passed through the hole in the bone which served as a handle or wrench while shaping the arrow. The shaft wrench was a popular tool among bison hunting groups.

Two varieties of shaft wrenches are found in western sites. One is made from a deer bone, usually the ulna from the foreleg, and the other is made from a wide flat section of bison rib bone. The deer bone shaft wrench was made using the whole bone for the most part, although occasional trimming of one joint end was done. The bone shaft which is tubular and hollow in cross section was perforated with a hole that passed through both sides of the bone. The circular perforation initially was between 9 and 11mm in diameter but as the wrench was used, wear from the arrows enlarged the hole and produced an oval-shaped perforation with the length of the perforation parallel to the length of the bone shaft. The wrench hole was placed toward one end of the bone so that the remaining section could serve as the handle. Most specimens are found broken across the perforation and show much wear.

Very little has been written about bone daggers, if indeed, that was their intended use. Daggers are most often made from the large leg bones of the deer. They are similar to the larger awls, but are much larger and heavier at the butt end, which is usually the joint end and makes a good working surface. Many of the examples from Tick Island, Florida and other locations have one or two perforations midway down the shaft. These may suggest some other use, or may have provided hafting or a strap to prevent loss during use. Some examples are engraved along the shaft, but most remain plain. These “Daggers” usually measure between 5 and 10 inches in length. Two of the largest examples known were from the Cushing site in Key Marco, Florida. One of those examples was made from human bone.

Bone and especially antler was the material of choice for tools including knives, of every size and shape awls, and knapping tools. Those pictured here are just a few examples of the various forms of hafting. Some handles may have been very small to hold gravers for delicate work. Alteration for hafting is not always evident on these handles other than the hollowing out of one end of the piece. Knapping batons have been known to be hollowed out on one end to accommodate an awl or replaceable antler tip for pressure flaking.

The scapula of larger animals like deer or bison were sometimes used as hoes or perhaps shovels. These are especially evident in sites located away from coastal areas where shell tools were not available. The shoulder blade or scapula was trimmed to remove the spine and rough sections along one face to form a large and fairly flat piece of bone. The bone was then hafted to an L-shaped wooden handle much the same as an adz was mounted for use. Some larger bison scapula have been drilled for hafting. These tools are often recovered broken or badly worn from use. The blade of the hoe would be highly polished from use.

Sickles for cutting grass, made from the lower jaw of deer, are found in sites across North America. Only one side of the jaw was used and this was lashed onto a wooden handle for service as a grass cutting tool. Grass was harvested for thatch for roofing. Actual examples of mounted specimens have been recovered intact from dry caves or rock shelters in the Ozarks area of Arkansas. It has also been suggested that these sickles were also used in harvesting corn. This tool was probably much more common than we realize as the bone was not modified or altered before being used as a sickle and those that had been mounted and used very little might be indistinguishable from an unused jaw. Many examples, however, do show wear along the teeth and the sides of the jaw bone are highly polished from use. The irregular surface of the adult deer’s teeth provided a saw-like cutting edge for collecting tall grasses that could be used for thatch. Wear from the lashing may be evident on the ascending ramus or articulating section of the jaw

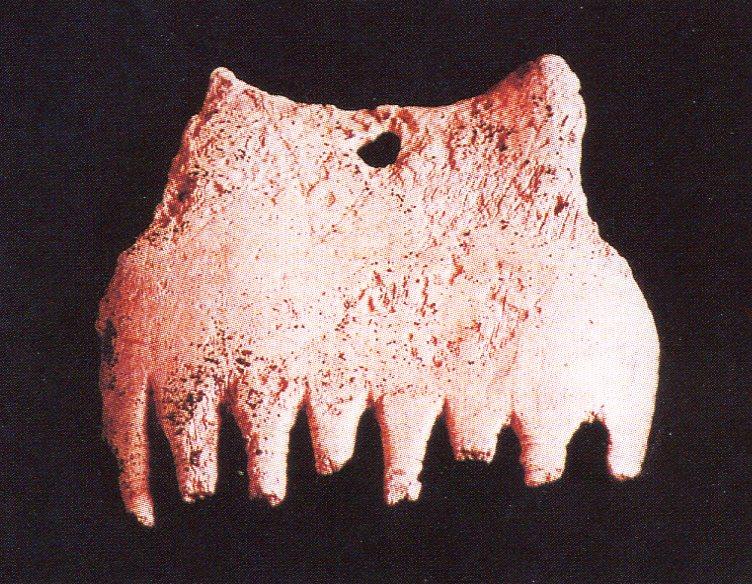

These artifact are made of antler or bone and are very rare. They were probably used much like a hair pin to keep hair in place rather than to “comb” hair as we do today. A comb was also used as a potter’s tool to create a rare type of pottery in northern Georgia called Rudder Comb Incised. This type was decorated by running a multi-tooth object, presumably a comb, diagonally along the vessel’s body. The design wound around the vessel from the rim to the bottom. Blank spaces were left between each comb stroke. This pottery type was recognized by Marion Heimlich at sites in the Guntersville Basin along the Tennessee River in northeastern Alabama and was found at both the Little Egypt site by david Hally and at the Etowah site by Adam King and would belong to the Middle Mississippian period. The use of combs extended from at least the Woodland Adena culture to Historic period sites where they are most often found.

The flute is the oldest known instrument beyond the human voice, dating to some 35,000 to 40,000 years in Germany. The instrument made by the American Indian is often referred to as a flute or flageolet, but was played more like a child’s recorder by blowing into the end and creating notes by covering the holes along the instrument with the fingers. Flutes are by definition, woodwind instruments played by blowing across an opening. These tiny instruments are most often made from bird bones, especially turkey bones. They are hollow and normally have three to five holes rubbed or drilled along the length of the bone, although examples have been recovered that have as many as nine holes in them. Most, if not all, of these instruments date to the Mississippian period and beyond. This same type of instrument, also made of bird bone, but with only a single opening, is referred to as a whistle and may have been used to call game birds.

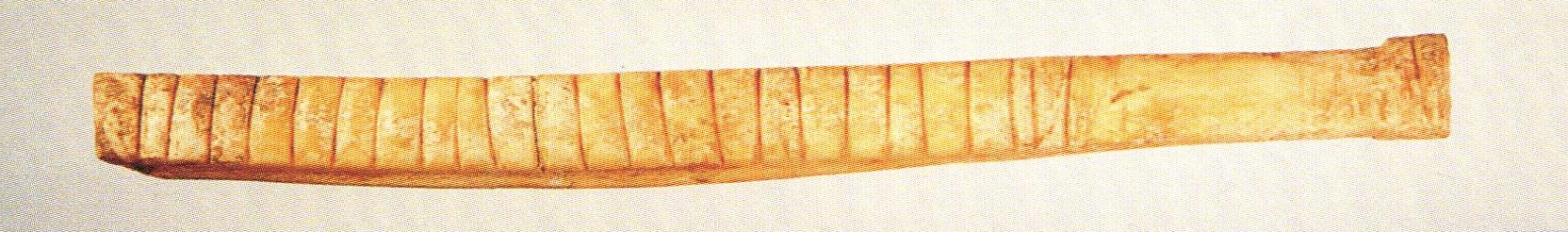

The rasp is a rhythm instrument that is often mistaken for a tally marker because of the many incised lines along it. The vibrating sound made by this instrument was produced by rubbing another stick or bone along its frame and across the incised lines.