Human effigy pottery gives us something akin to a photo album for the early cultures before European contact. The subject matter included men, women, and children as well as sports heroes and important political leaders, much as it does today. The faces reflect both social and religious values, both in the dancers of the Southern Ceremonial Complex and in celebrations like the Corn Dance.

First grown in Mexico about 5,000 years ago, corn soon became the most important food crop in Central and North America. Throughout the region, Native Americans, Maya, Aztecs, and other Indians worshiped corn gods and developed a variety of myths about the origin, planting, growing, and harvesting of corn (also known as maize).

Corn Gods and Goddesses. The majority of corn deities are female and associated with fertility. They include the Cherokee goddess Selu; Yellow Woman and the Corn Mother goddess Iyatiku of the Keresan people of the American Southwest; and Chicomecoatl, the goddess of maize who was worshiped by the Aztecs of Mexico. The Maya believed that humans had been fashioned out of corn, and they based their calendar on the planting of the cornfield.

Male corn gods do appear in some legends. The Aztecs had a male counterpart to Chicomecoatl, called Centeotl, to whom they offered their blood each year, as well as some minor corn gods known as the Centzon Totochtin, or “the 400 rabbits.” The Seminole figure Fas-ta-chee, a dwarf whose hair and body were made of corn, was another male corn god. He carried a bag of corn and taught the Seminoles how to grow, grind, and store corn for food. The Hurons of northeastern North America worshiped Iouskeha, who made corn, gave fire to the Hurons, and brought good weather.

Origins of Corn. A large number of Indian myths deal with the origin of corn and how it came to be grown by humans. Many of the tales center on a “Corn Mother” or other female figure who introduces corn to the people.

In one myth, told by the Creeks and other tribes of the southeastern United States, the Corn Woman is an old woman living with a family that does not know who she is. Every day she feeds the family corn dishes, but the members of the family cannot figure out where she gets the food.

One day, wanting to discover where the old woman gets the corn, the sons spy on her. Depending on the version of the story, the corn is either scabs or sores that she rubs off her body, washings from her feet, nail clippings, or even her feces. In all versions, the origin of the corn is disgusting, and once the family members know its origin, they refuse to eat it.

The Corn Woman solves the problem in one of several ways. In one version, she tells the sons to clear a large piece of ground, kill her, and drag her body around the clearing seven times. However, the sons clear only seven small spaces, cut off her head, and drag it around the seven spots. Wherever her blood fell, corn grew. According to the story, this is why corn only grows in some places and not all over the world.

In another account, the Corn Woman tells the boys to build a corn crib and lock her inside it for four days. At the end of that time, they open the crib and find it filled with corn. The Corn Woman then shows them how to use the corn.

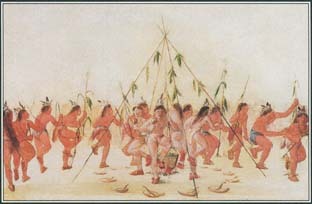

Native Americans of the Southeast hold a Green Corn Dance to celebrate the New Year. This important ceremony, thanking the spirits for the harvest, takes place in July or August. None of the new corn can be eaten before the ceremony, which involves rituals of purification and forgiveness and a variety of dances. Finally, the new corn can be offered to a ceremonial fire, and a great feast follows.

This painting by George Caltin shows the Hidatsa people of the North American Plains celebrating the corn harvest with the Green Corn Dance. The ceremony, held in the middle of the summer, marks the beginning of the New Year.

Some legends state that the Corn gods were responsible for man’s creation. Mud and wood had failed,but the corn people were perfect. However, the gods decided that their new creations were able to see too clearly, so they clouded the people’s sight to prevent them from competing with their makers.

Sports figures were prominent in human effigy figures because the sports they competed in were central to both village life and the interaction between various village groups. The vessel above was recovered with the discoidal that still rests inside it. The lug handle on the opposite side of the human figure is shaped much like what appears to be a carved steatite throwing cup for just such a discoidal pictured below from Monroe County, Georgia.

Cultural studies have shown that the making of pottery is a task typically assigned to women. This seems to have been true in Native American society as well. Because women were focused on the issues of daily life in the Middle World, the figures that were given shape, either by the addition of appendages or by the use of the entire vessel, reflected the values of daily village life.

That is not to say that women were not involved in mortuary or ceremonial matters. The inclusion of highly decorated pottery and / or figurines indicates quite the opposite. But, for the most part, ceramic figures associated with pottery reflected Middle World values and relationships including food sources and mystic thought.

This Dallas vessel in the shape of a fish (Dallas Modeled) gives clear indication of the importance of fish to the diet of this northwestern Georgia people. In fact, there are many fish weir or trap sites along the rivers of northwestern Georgia.

This vulture effigy water bottle from the Etowah Mound complex (Etowah Red Filmed) did not represent a food source, but a mystic belief about some bird species including the vulture.

Likewise the owl did not serve as a food source, but was believed to have unique powers. The owl was affixed to the rims of some vessels at Brown’s Mount (left) near Macon, Georgia (Brown’s Mount Plain) during the Early Mississippian period. The dominance of this belief is demonstrated by the Halstead Plain water bottle (right) from the Macon Plateau just a few miles away that is also in the form of an owl. During this same period and extending into the Historic period, the Jororo people living along the St. Johns River near Hontoon Island erected an own totem at their village site. The totem dated to A.D. 1300. Swanson’s use of the Spanish name Jororo seems to be derived from the Timucuan Hororomeaning owl.

It is interesting to note that these adornments to pottery did not occur until the Hopewell based interaction between groups of people became prevalent near the end of the Deptford period between A.D. 150 and 500. The figurines that appeared during this period were soon followed by figures that appeared as ceramic appendages on pottery vessels. Until that time, motif design consisted primarily of different configurations of straight lines, curvilinear lines, or punctations.

Even though effigies involving the whole vessel or simple appendages continued into the Late Mississippian period, the majority of both Woodland and Mississippian cultures did not employ them in ceramic design. Most cultures continued with simple linear or curvilinear lines and punctation or employed the symbolism of the Southern Ceremonial Complex in pottery motif design. The potters of Georgia that used effigy figures included the Lamar, Dallas, Etowah, Halstead, and Brown’s Mount groups.

This canoe effigy bowl (shell tempered Dallas Modeled) from Gordon County, Georgia reflects the Middle World thinking of subsistence and travel. This would be the equivalent of modeling a nice sports car into a bowl today.

Lamar potters produced this Owl effigy “rattle head” pot in Hancock County, Georgia. The potter who made this vessel may be the same potter that made the “rattle head” human effigy bowl from the Bruce Butts collection.

Some animal forms can leave us guessing while others are commonly used and clearly recognizable.

Florida groups like the Fort Walton people that entered southwestern Georgia during the Early Mississippian period also used these effigy figures extensively. One example is the alligator effigy used to decorate the bowl at the top of this article. The examples above are a few of the Fort Walton effigy appendages that have been recovered. It is believed that the Fort Walton culture grew directly from the Weeden Island culture, thus the tendency to use effigy figures may have been passed down through their generations.

Apparently most Native Americans enjoyed the delicacy of frog legs as the frog is a popular effigy topic across the Southeast. Frogs weren’t the only thing that Arkansas Indians had a taste for. Razorback hogs were a popular topic of effigy pottery, and it doesn’t seem that the football team was on the field in those days, even though this hog was done in Nodena Red and White style. And what was Mr. Indian doing while Mrs. Indian was hard at work doing all that pottery making and cooking?

That’s right, ladies! Men just haven’t changed all that much. After eating the razorback, today’s man watches them on TV, not so different than his Native American counterpart! And, no, this isn’t an animal effigy, it’s more of a vegetable; a couch potato.