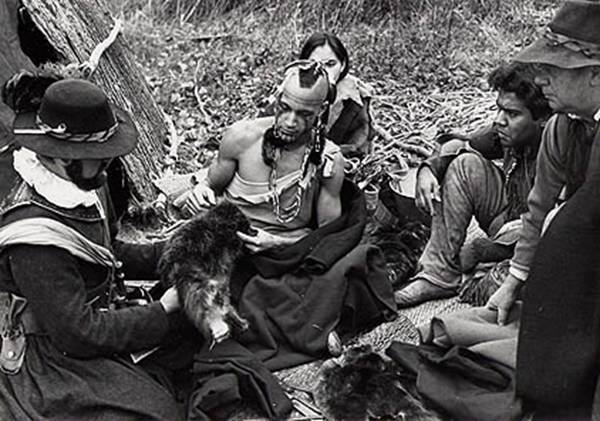

The earliest known fur trade was carried on by unrecorded fishermen and coastal travelers that seem to have protected their monopoly on trade through a conspiracy of silence. It is not known precisely when this trade system began, but it seems certain to have begun during the 1400’s. Trade was carried on at coastal ports by white settlements, but did not involve any established trading posts or stores. Those would become established during the third stage of trade after 1600. Those shoreline settlements that did exist have largely been destroyed by erosion or farming activities. The evidence of early trade is remarkably sparse. Perhaps the major trade goods consisted of perishable materials such as woolen fabrics or hemp that may have been important commodities. The slim evidence of white settlements and related documentation has left archaeologists to rely on the presence of trade goods within Indian sites. European goods are useful in dating aboriginal sites, but in nearly every instance, the dates for specific types of European-made objects have to be derived from the archaeological contexts because literature and other sources from Europe contain little to no information about the manufacture of common goods such as axes, kettles or hoes.

Indian sites that date to this stage are extremely difficult to identify and interpret. Each village normally includes a single piece of European brass, usually in the form of a delicately made and finely joined tubular bead. What little trade items that exist are concentrated in only a few graves.

A Seneca village in the Genesee Valley, New York is the best studied site of this stage. It yielded one brass bead, and less than 1 per cent of the graves contained European goods. The trade objects are quite different from those of any later stage. They are not goods made for the Indian trade, nor are they the ordinary domestic objects of Europe; they reflect the ways of the sea. Among parts stripped from ships are bolts, metal rings from rigging, and metal tips from belaying pins. Broad, thin knives appear to have been specialized tools of the fisherman. Spiral brass earrings, worn in the left ears of Indian burials, represent a direct transference of the ancient sailor’s caste mark; this was the seaman’s charm against bad eyesight. Strings of glass beads, especially in blue, probably came from sailors who wore them as a protection against the evil eye. Thin-walled tubular beads with large openings, spherical blue beads of a widespread type, and faience beads formed upon a sub-spherical clay core are characteristic.

Context data for trade goods has also been derived from occurrences in documented house sites of early settlers and from artifacts found on the sites of military operations. Military camps of short duration and houses which were burned at a known time have provided critical samples, but all sites have yielded valuable source material for the history of European technology. Craft objects which are intermixed without regard to date in the superficial layers of European sites may be found delicately separated by decade in the sites of Colonial America.

Spanish exploration in the Southeast provided another datable context through the chronicles of their journeys. Indian towns in the Southeast such as Talisi, located at the present site of the city of Childersburg, Alabama have contained artifacts known to be associated with these explorations. In the 16th century, people identified as part of the Kymulga-phase culture (a local expression of the larger Mississippian culture) lived at Talisi. In the fall of 1540, the Spanish expedition lead by Hernando de Soto rested there for about one month. One common artifact type that is frequently recovered from sites visited by de Soto is the Nueva Cadiz bead. The presence of these beads in burial mounds like the Tavares mound in Lake County, Florida and the Little Manatee mound in Hillsborough County, Florida are a clear indication of Spanish contact during this early period.

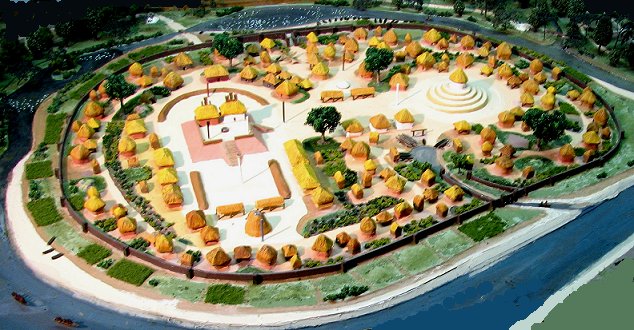

In 1540 the expedition of Hernando de Soto also recorded its travel through the chiefdom of Ichisi. Historians and archeologists agree that this was likely the Late Mississippian Lamar period town of Ochessee. Ocheessee is located about five miles from the Ocmulgee National Monument and the Ocmulgee mound complex.

From the landing of Ponce de Leon in 1513 on the shores of La Florida to the decimation of the Spanish mission system in 1704 by Col. James Moore, the Spanish brought trade items to the Indians of Florida, southern Georgia and southern Alabama. While it might not be fair to consider them items of “trade,” the gold and silver treasurers of Spain fell into the hands of the Calusa people of south Florida. The storms of the Gulf of Mexico often blew the Spanish treasure galleons off course and into the Florida Keys where the Indians living on Matecumbee Key salvaged them of their cargo. From the silver coins, the Calusa fashioned ceremonial tablets that have been found as far north as the St. Johns region of Florida. These are a marker for the period, but were distributed by the Calusa into the areas of tribes that were under Calusa control and not by the hands of Spanish traders.

These Calusa ceremonial tablets of silver, copper and brass are typically found in burial mounds in areas of southern and central Florida that were controlled by the Calusa chiefdom. C.B. Moore recovered two of these, one of silver and one of brass, from the Gleason Mound in Brevard County, Florida.

Several other types of pendants were recovered by Moore in Florida sites that reflect this same general early stage of trade. (A) Gold pendant from a mound near King Philip’s Town in Orange County, Florida, (B) Gold pendant from the Thursby Mound in Volusia County, Florida, (C) Silver pendant also from the Thursby Mound in Volusia County, (D) Silver pendant from the Dunns Creek Mound in Putnam County, Florida. This last burial was probably intrusive to the mound as the remaining artifacts date to the Middle Woodland period.

Jean Ribault founded the French settlement of Ft. Caroline at the mouth of the St. Johns River in Florida in 1564 and the Spanish founded St. Augustine in September of the following year. After their destruction of the French settlement at Ft. Caroline, the Spanish began to establish a mission system among the Native Americans across northern Florida and southern Georgia. The mission towns also served as early trade settlements.

These axe heads have been sawn into chisels. To the right is a bail tag used to tag the bails of furs traded by the Indians.

Even though the Spanish swept through the Indian towns early in this period to remove iron implements, the native populations were eventually allowed to retain iron tools such as axes. Iron axes were so precious that they were sawed with slabs of sandstone into narrow chisel-like blades, and eyes were ground into adz blades. Sawed-up axes, some of the bead types, large knives, brass kettles that were cut up into ornaments and knives, bail tabs which held the bails of hides together and ship fittings are considered diagnostic trade items of this earliest stage.

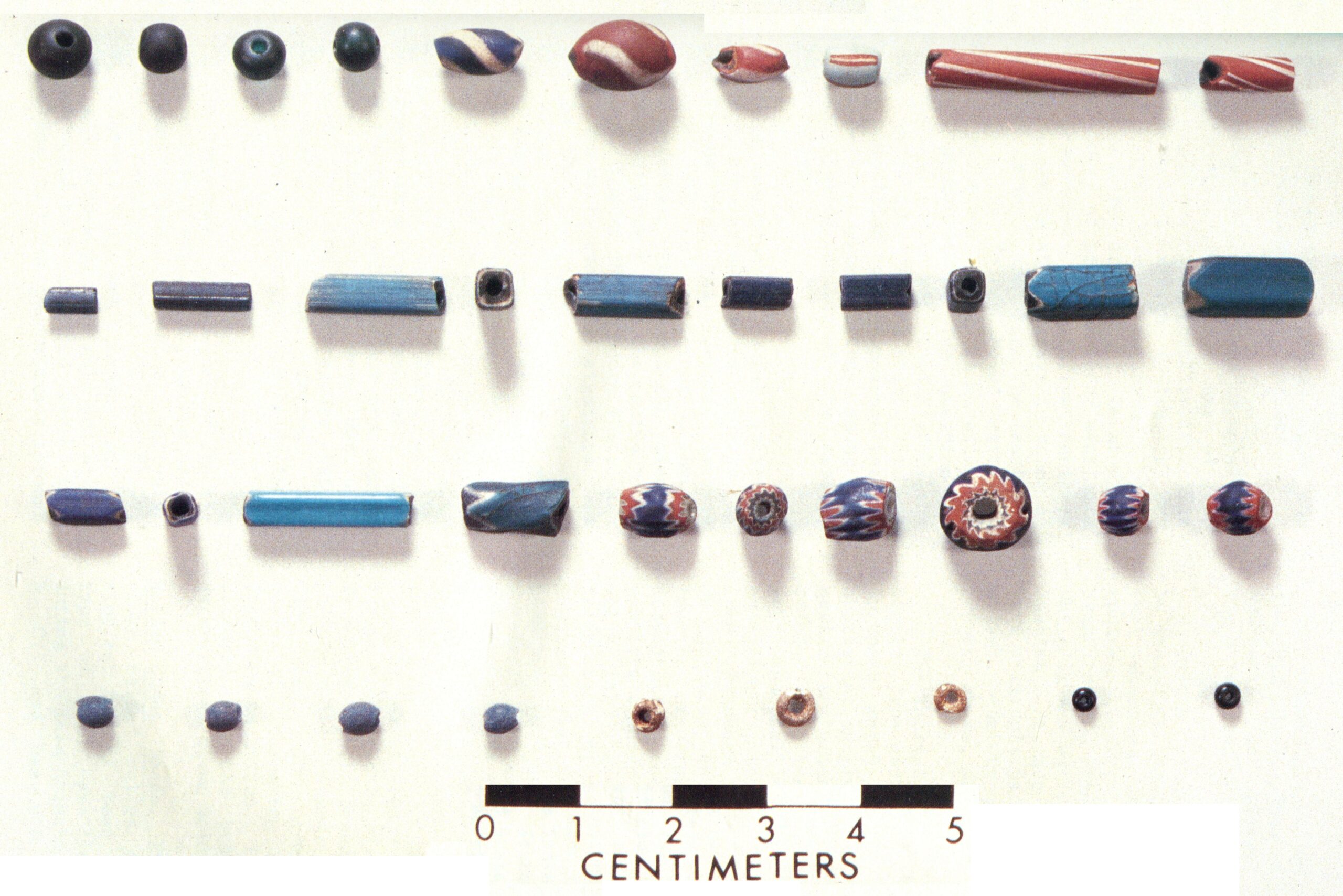

Glass beads are the most useful gauge for dating American Indian sites of the Colonial period. They occur in abundance and were subject to rapid changes in technology. There are many distinct types — more than a thousand in North America — and their styles show a pattern of cyclical recurrence, with only minor differences to distinguish the beads of one decade from those of their recurrence five or more decades later.^ But given correct identification, they permit very precise dating. Moreover, bead types seem to be international in their distribution, and their dates appear valid on a world-wide basis. Systematic studies of the trade bead types of North America, Africa, Asia, India, and South America will no doubt lead in time to new insights concerning European glass manufacture and world commerce in this era.

The above chart of Spanish trade beads from the Tatham Mound in Citrus County, Florida was created by Jeffery Mitchem and Jonathan Leader. All of these bead types are known to occur between 1500 and 1560. The bead types include: (row 1) Spherical Dark Navy Blue, Barrel-shaped opaque light blue with white on red stripes, Olive-shaped translucent red with 3 spiralling opaque white stripes/opaque brick red/pale, White spiraling stripes/opaque brick red/pale blue-green core, (row 2) Nueva Cadiz Plain, Twisted and Faceted beads, (row 3) Nueva Cadiz and Faceted and non-faceted Chevron beads, (row 4) Olive-shaped translucent green wire-wound beads, small donut-shaped reddish-purple wire-wound beads, and sub-spherical translucent dark purple seed beads. There are over 1000 types of trade beads that appear at different times throughout all four stages of the colonial fur trade system. For a more complete look at glass bead history, see our History of Trade Beads article in this section.

Chevron beads also characterize the early Spanish period in Florida, and we suspect that they were also among the earliest trade beads in the Northeast; however, Chevron beads have not yet turned up among the small samples available in sites from the first stage in the fur trade. Glass beads seem to be absent from living areas; most are found with infant burials. The most distinctive and numerous object is an oval glass bead, opaque and ranging from faded white to jade green to blue in color. It is found only in this horizon. Chevron beads are more numerous than in later sites. Although found in small percentages as late as 1640, they are abundant only in sites earlier than 1600. Flush-eye beads are also diagnostic of sites from the second stage of the trade. Both chevron and flush-eye types are closely related to Islamic mosaic glass.