The 1590s brought a revolution in the fur trade, with a vast increase in European contacts. Beginning somewhat before 1600 and extending into the 1620s, this stage coincided with the first successful French, British, and Dutch colonies but probably had little connection with them. Many trade objects which are well known from Indian sites have never been found where white settlements existed nor in the port towns.

Colonial Jamestown, Virginia was founded in 1607 as the first permanent English settlement in the New World.

A conspicuous example may be noted at the Jamestown settlement that was founded in 1607. There, despite the abundance of glass trade beads in contemporary Indian sites, practically none have been found in the excavations at the settlement. On the other hand, the pottery tableware and clay pipes so conspicuous at Jamestown are barely present in nearby Indian villages.

This stage of the fur trade is also marked by a reorganization of aboriginal power centers in the northern U.S. The Huron, Iroquois, Susquehanna, Powhatan, and Cherokee became the great middlemen in the fur trade, trapping, buying, and looting beaver from the continental interior and carrying it to nearly depopulated coasts for rendezvous with sailing ships. Very few European objects traveled west of these five native political groups; most trade goods stayed in their towns. Intertribal wars began for control of the trade and for access to interior beaver hunting lands.

Late sixteenth-century sites of the Gulf drainage basin are even less known than their northern counterparts. In the coastal plains and piedmont of the Southeast, major Indian villages which probably date from the late 1500s have not yet produced European objects. Trade goods from the late sixteenth century are almost as little known as those of the first stage. Village sites are thinly scattered with brass and iron scrap, so that any token excavation produces a brass bead.

Knives were perhaps the most important and revolutionary trade item. They transformed the natives out of the Stone Age and had completely replaced flint knives. Knives, even more so than the axe, could be used for many things – in particular the “Dag”. The dag was fashioned after the large stone spear points. It was strong and could be used for heavy chopping, as a spear point, a utility knife, skinning and butchering, a spear point and as a weapon. They were shipped to North America from Europe by the barrel load. There were also made by resident blacksmiths in the trading posts. They were traded without handles. The handles were usually ornate and made of wood and often tacked. Some beautiful knives were made with a bone handle with a serrated copper ring at the top for a scrapper. They are often seen with a universal “circle” and “dot” design in the bone. They most have been very common in the mid 1800’s as early explorers noted natives wearing them with a thong attached to their wrists. They are often marked with a makers name such as “Jukes Coulson, Stokes & Co.” or “IS” for John Sorby. Some very desirable dags are marked with a “Circle” and “Sitting Fox” design which was traded by the North West Company. They are also known as the “Columbia River Knife,” or, in some areas, it was called a “Beaver Tail Knife.”

Other knives known to the fur trade were the Russell Trade Knife (left) and the Wilson Knife (right).

Most knives are found in archaeological sites and have been reduced to rusted strips of metal that may resemble a knife form or a bar of metal, but would be found with other metal objects.

Axes are present during the early 1600’s, but not abundant. A few steel axes were sawed into smaller tools. The most commonly found style of axe heads are known as the “French” style, or “Biscay” style – since they were manufactured in the Biscay region of France. The Hudson Bay Company Trade Axe came in at least two forms, the standard trade axe (left) and the “squaw” axe (right).

Trade axes are perhaps one of the most important and essential trade items produced. The axe is a multipurpose tool. It was used for every day uses as well as for ceremonial purposes and could be used as a weapon when needed. These axes were imported from European countries by the thousands, although many were made on site at trading posts and forts by blacksmiths.

Axes made by blacksmiths at trading posts (left) were hand forged, made from a single piece of iron, heated and folded over a mandrel to make an “eye” or hole for the handle and forge welded together. These axes are sometimes referred to as “Lap-weld” axes. Early axes had round “eyes” or holes. Later the eyes became tear-dropped or oval shaped and later still rectangular. Handles were made by the natives or by white-traders. Many axe heads had maker’s marks commonly referred to as “touch marks”.

Touch marks were usually made with an iron “touching” the axe head when it was red hot, making a mark (above left). Cast or factory made axe heads with makers marks are often referred to as “guild marks” as seen on the British camp axes.

There are many other styles such as Spike axes, Double flared blade axes, and Trapper’s Axes or Hudson’s Bay Axes that have a notch in them to catch hold of a trap or chain.

There is also the classic Tomahawk style which often has a “Pipe” stem. Peace Pipe Tomahawks were mostly made for ceremonial purposes and denoted status. Elaborate Peace Pipe Tomahawks are highly prized by collectors. There are many other shapes and styles of axes.

Brass was known, but kettles were still cut up rather than used as cooking utensils. The first brass kettles appear in graves. Copper kettles, trade kettles or copper pots were all traded by the Hudson Bay Company as were brass trade kettles and brass pails. Copper Kettles came in various sizes from very small, 4 inch in diameter to very large. They were usually stamped with the size ie. 1 QT (one quart) or 3 PT (3 pints). They have a very characteristic pattern and are elaborately made for a “simple” camp pot. They are made of copper or brass.

Early pots have “dove-tailed” seams. Later pots were extruded. The lid has a free-floating ring riveted in place with an iron keeper. The edges were rolled and the inside was lined with tin. They also have an elaborate rim to stop the lid from going down to tight. The bale is secured on both sides with an elaborate round iron bud, or “ear” riveted to the side of the pot. The pots are made with heavy gauge metal – evidence that they were designed for heavy use and long lasting durability. The designer also thought about the transportation and storage of these pots, both for shipping and in the field. Because of the various sizes they can be “nested” inside each other to cut down on space.

Most of the Native Americans had ceased to use stone ax blades and were being entirely supplied with iron ones. It is estimated that half of the adz and hoe blades were stone and half were iron.

Trade harpoons and spear points were used to hunt mammals and fish. Fish spears had muli-tang points with barbs. Beaver and muskrat harpoons were long shafts with two offset barbs. These were made in Europe and shipped to the Colonies or more often were made by the fort blacksmith from scrap metal or old files. Harpoons were made with detachable points with line attached so they could retrieve the game.

Arrow points were cut out of metal using an old trade axe head as an anvil and a chisel to cut out the point. Arrowheads were cut from sheet brass or iron including the Kaskaskia point used by the Creek Indians in Georgia and Alabama, but flint tips were predominate. The Guntersville and Mississippian Triangular points were the most widely used stone arrow points.

Bottles that date to the 1600’s have some distinctive shapes. The bottles were hand blown and have a small groove around the lip of the neck for suspension by a string until the bottle cooled after blowing. Bottles of this period were reused, filling them again and again with rum or whisky and may have the owner’s name etched into the glass. Whole bottles or fragments of the black or dark green glass are found occasionally in aboriginal sites where they were occasionally made into arrowheads or pendants.

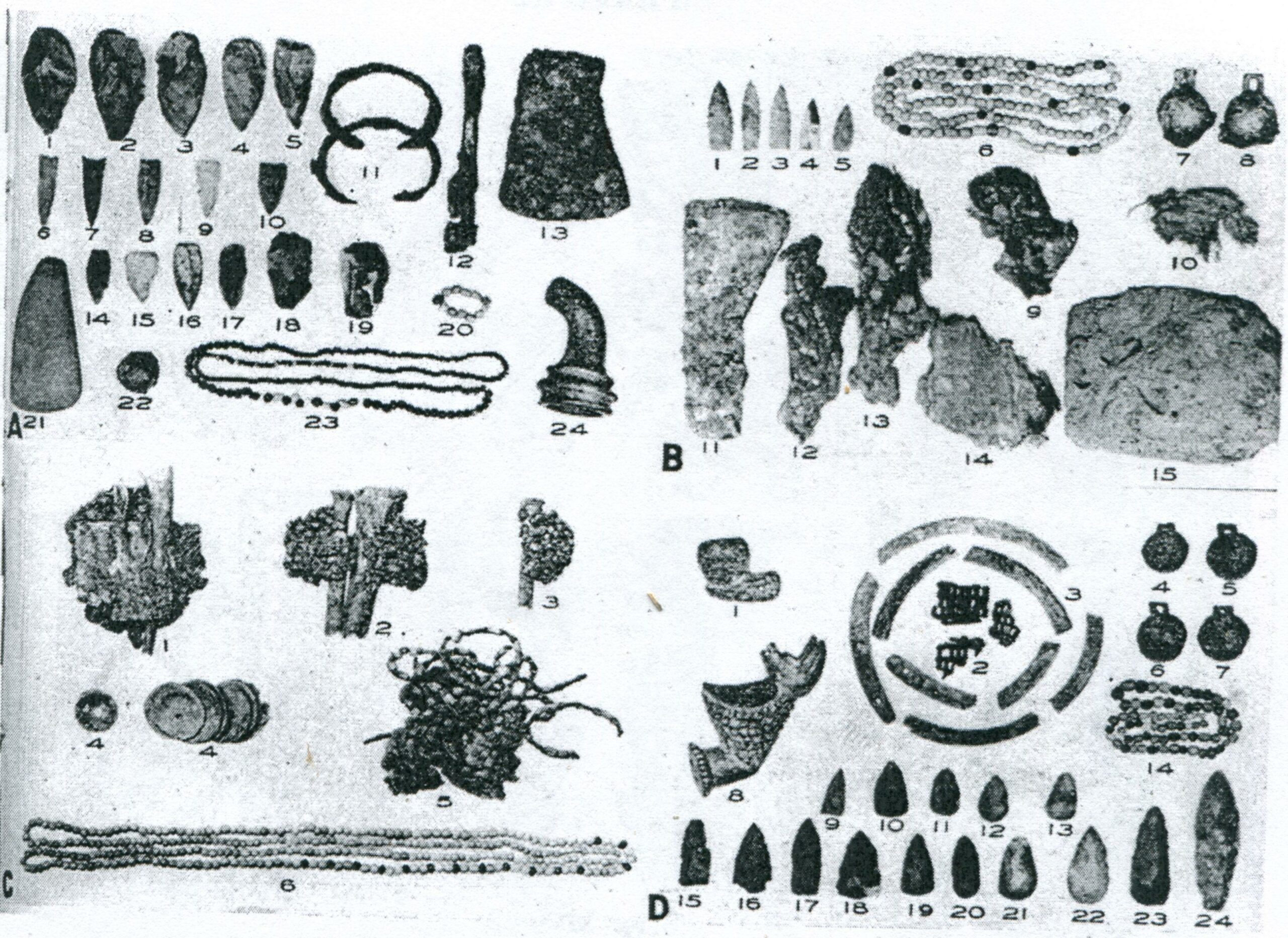

This assortment of beads and other trade goods illustrated by William Webb and Charles Wilder from four burials excavated at the Ms32 site in the Guntersville Basin demonstrates the volume and types of trade materials present in aboriginal village sites during the 1600’s. The content of these burials included fiber fragments and buckskin materials, blue glass beads, blue and white glass beads with brass clips, trade axes (one trade and one a squaw axe), hawk bells, iron bracelets, rings, an iron knife, brass arm bands, perforated brass discs, brass and copper clips or broaches, blue and black glass beads and several brass collar bands.

Glass beads occur in profusion and variety. They are concentrated in graves but are also broadcast throughout the village sites. The majority of the beads are of a type or series of types which we have called “early blue.”^ This bead type is found as a tiny minority in sites from the first and second stages of the fur trade and in sites as late as 1650. It may have been in existence at the time of the earliest trade, but it is overwhelmingly abundant just before and after 1600. It is a small, spherical to oval, sky blue bead of weak glass, filled with capillary bubble holes and strains parallel to the hole. It weathers and etches very badly in alkaline soil, and it is normally so weak and damaged that it is not recovered from sites dug over by collectors. Many examples have longitudinal stripes in white. Despite the long period over which this type appears, it is a good, sensitive dating device. When it is predominant — even in a small sample — the date is close to 1600. Practically all of the other bead types of this stage are spherical or sub-spherical, with almost no cylindrical or tubular examples. All have dull surfaces, none of them being coated with transparent clear glass, as are the beads of the next stage.