This reconstructed trading post was established during the third stage of the fur trade and dates to the 1600’s. It was built at Quebec, Canada at Sault Ste. Marie.

The third stage of fur trade, marked by the first appearance of firearms in northeastern sites, is usually merged into sites with a longer occupation that can only be segregated through study of grave-lot association. However, one Seneca site near Rochester Junction, New York, was occupied for just the proper interval to define this stage. It is believed to date from about 1630.

Between 1633 and 1704 the Spanish mission system brought cultural change to the native people of Florida and southern Georgia through their conversion to Christianity. Much of the day-to-day life of the Indian populations remained unchanged because of its similarity to peasant Spanish life.

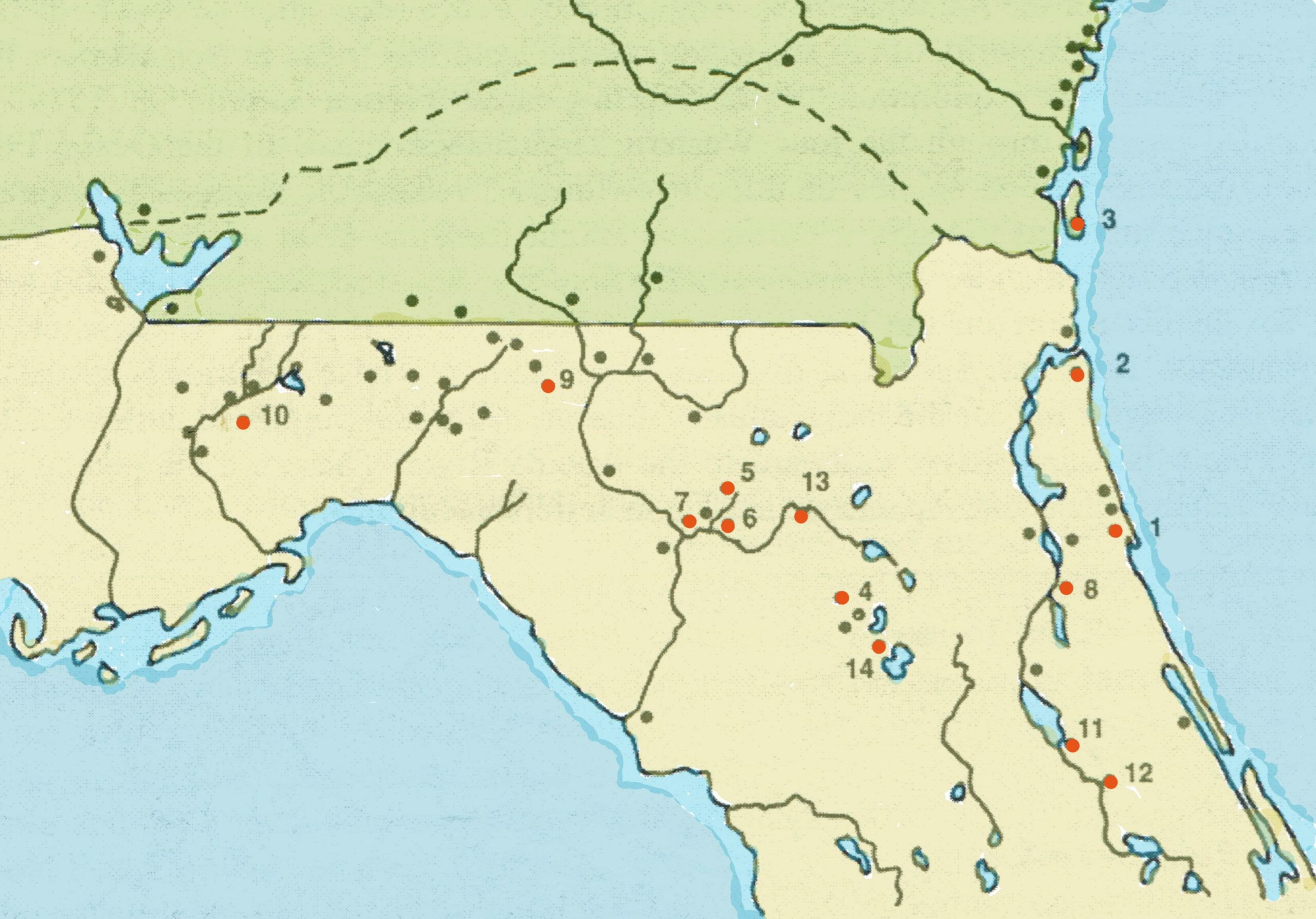

Fourteen of the sixty Spanish missions that are illustrated on this map include: 1) St. Augustine, 2) San Juan del Puerto, 3) San Pedro de Mocama, 4) San Francisco de Potano, 5) San Martin de Ayaocutu, 6) Santa Catalina, 7) Ajoica, 8) San Diego de Salamototo, 9) San Pedro y San Pablo de Potohiriba, 10) San Luis de Talimali, 11) San Salvador de Myaca, 12) Atoyquine, 13) Santa Fe de Teleco, and 14) Santa Bueneventura de Potano.

Much of the Spanish influence can be seen both in the missions themselves and in the local villages of the area. The reconstruction of Fort San Luis and the mission of San Luis de Apalachee is located on its original site in the city of Tallahassee, Florida.

The fort and mission house at San Luis de Apalachee

A fragment of the mission bell and some Spanish pottery from the San Luis de Apalachee mission sit

The vessels above are Ocmulgee Plain from Houston County, Georgia (left) and Miller Plain from north-central Florida (right).

The influence of the Spanish on Indian populations is demonstrated in the Kasita Red, Ocmulgee Plain and Miller Plain copies of European wares that are recovered from Indian sites of this period. Many of the other artifacts from aboriginal sites of this period consist of iron nails, awls and beads.

This delft plate (left) was recovered from a Historic period Creek village site in Georgia and dates to the 1600’s. The plate measures about five inches across and has been rounded at the edges and drilled for use as a gorget. The game pieces, some of which were cut from broken delft plates and some from native pottery, were recovered from a colonial period Indian village. The button may have been a child’s toy “whizzer” to be played with on a string.

Discs cut from broken delft plates are found in Indian sites of this age. Similar discs from Colonial white sites, such as Brunswick Town, North Carolina, are interpreted as checkers. Since there are no European dishes in the Indian sites of the same age, the discs probably were gaming pieces made in white settlements.

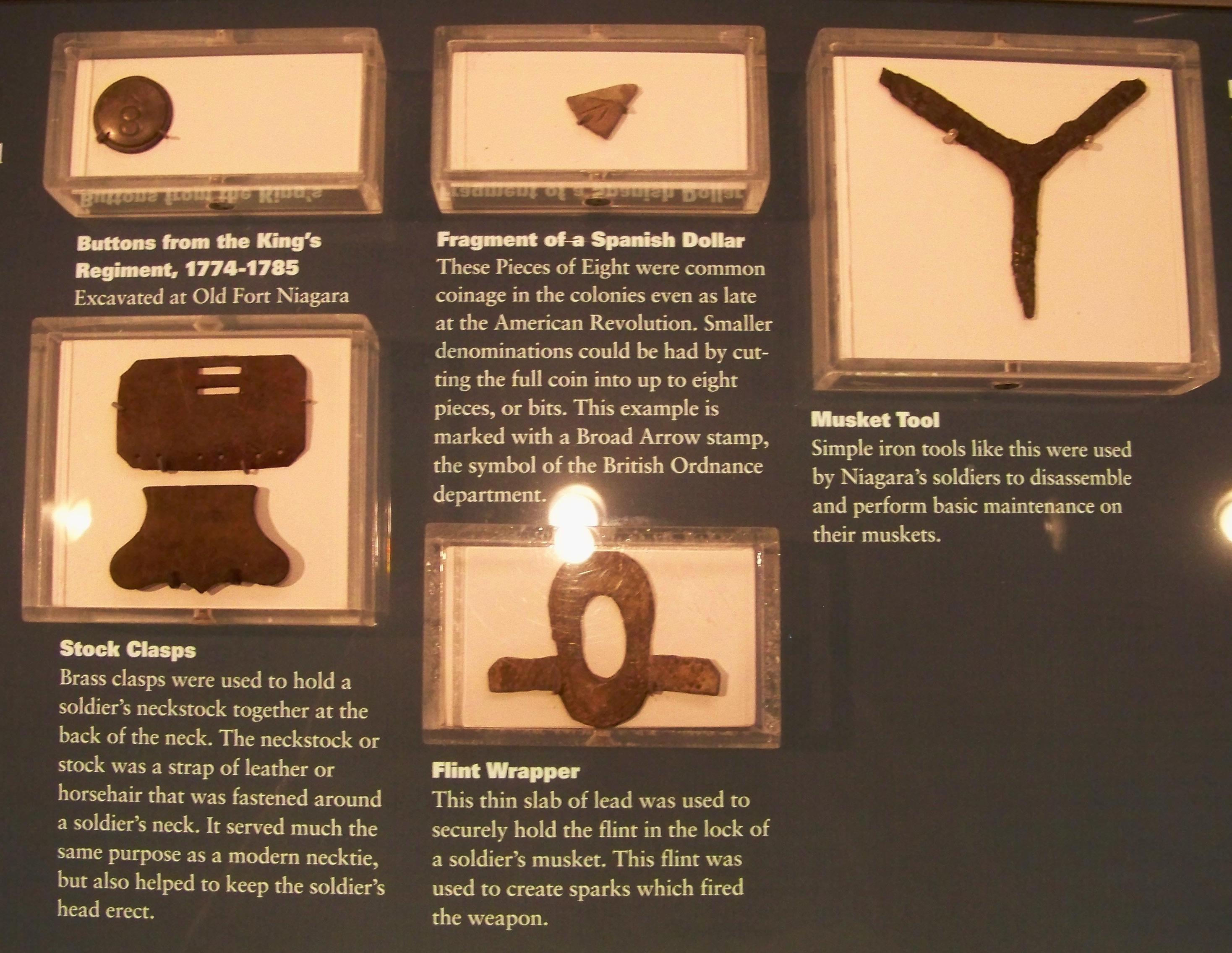

Both the British and Spanish were hesitant to trade guns to the Indian populations until the French began to use them as trade items in Canada and the area of the Great Lakes. The guns were mainly primitive or transitional flintlock mechanisms: snaphaunces, dog locks, and Jacobean locks. The sudden abundance of firearms, coincident with the early period of invention in firelock mechanisms, speaks eloquently about the economic importance of the fur trade. As guns became more abundant, arrowheads diminished in number.

English matchlock musket ca. 1600 to 1660

Crafted in the Swedish style, this matchlock musket was typical of the matchlock musettes used in both England and France during the first half of the 17th century. Indeed the Dutch and several German states took into use similar designs for their musketeers. It’s wide use is documented in numerous drill manuals of the time along with numerous surviving examples (specimens in the Musée de l’Armée in Paris, the Tower of London, and the Royal Ontario Museum) . During the English Civil War this was considered a Regimental pattern and barrel lengths appeared to have varied from 42″ to 48″ inches. By 1660, this design had become obsolete in most armies. However some were retrofitted by replacing the lock with a newer design such as a dog lock. A beautiful example of this was found archaeologically off one of the sunken ships of Phipp’s New England Army that attempted to capture Quebec in 1690. In addition as matchlocks were sold off, it is likely they would have found homes with the 17th century Pirates on the high seas.

The Hudson Bay Company Trade Gun 1670

When you mention the words “trade gun” the first gun that comes to mind is the “Northwest Gun” but, there were trade guns around long before the classic northwest gun was made. The French started trading guns or “fusils” to the natives in the early sixteen hundreds as did the British and the Dutch in colonial America. It wasn’t until the Hudson’s Bay Company started their company in the 1670’s that trading guns was done on a large scale. The guns themselves were not made by the Hudson’s Bay Company. The company secured contracts for trade guns from many different gun manufacturers. Some have the initials of the makers under the barrels. Many examples have the maker’s name on the lock plate; Names like Wilson, Sunderland, Wheeler, Barnett, Hollis, Ketland and Parker Field & Son.

The Northwest Guns came in various barrel lengths and are noticeably apparent by their “serpent” or “dragon” side plate and oversized trigger guard. Most people believe the name Northwest Gun was derived from the name of the North West Company but, in fact the gun was called the Northwest Gun long before the company was formed. The North West Company stamped a “Sitting Fox” in a “circle” on the butt of the stock and also on the lock plate and on top of the barrel. After the union of the two companies in 1821 the Hudson’s Bay Company used a stylized “Tombstone Fox” cartouche stamped in the lock and on the top flat of the barrel. They were a .60 caliber smooth bore which could be loaded with a single round ball or with shot. Even though they were cheap to make, the guns were very reliable – evidence in that many of these guns found today are still functional. By the 1840’s trade guns were being produced in the “new” percussion ignition system. Percussion caps cost money so many native and white trappers preferred the flintlock system. Flintlocks were still being manufactured right up until 1875. Some trade guns were embellished and known as “Chief’s Grade” guns and were given to chiefs to form important military alliances or when signing treaties.

The Barnett trade gun 1754 – 1850

American gun makers such as Tryon, Leman and Deringer also made trade guns. They each had their own distinct design but some guns were made in a similar likeness to the Northwest gun – right down to stamping British proof marks onto the barrel. It is believed that Lewis and Clark carried the U.S. Model 1803 muskets to trade with the natives on their exploration of discovery in 1804. Trade guns were used and carried every day. Some with long barrels were cut down for ease of maneuverability in canoes and on horseback. It is a myth that traders made the natives pile up beaver skins as high as the barrel in order to buy a trade gun. Prices were very much standardized across the country. In the midst of the trade a gun was worth about 16 beaver skins. Prices went up and down throughout the centuries with supply and demand, and inflation. If you consider the price of a “new” trade gun today and what it costs to buy a beaver skin, not much has changed in two hundred years.

There are some very early trade pistols with serpent side plates that were made for the trade. There are also some later flintlock pistols made in the early eighteen hundreds of a particular style which are called “Trade Pistols” but, not everyone agrees that they are a “true” trade pistol. The trade gun changed the way of life, and in some cases death, of the native people.

This collection of gun flints was gathered from several sites in northwestern Georgia.

The gunflint industry went through a succession of technological stages. European literature and manuscript sources provide little information, practically all of it later than 1780. Most of what we know about early gunflints has come out of American soil, and our dates for steps in the evolution of the fire flint depend upon site contexts in North America

The powder horn show above (left) is made from the horn of the eastern woodland buffalo. These animals had a brown horn rather than the black horn of the western buffalo. Eastern buffalo were hunted to extinction prior to 1700, making this horn at least 300 years old and almost certainly the creation of an American Indian during the Fur Trade era.

Tom Grinslade wrote in his book Powder Horns, Documents of History, “The use of cow horn as a powder container predominated in America from the early eighteenth century into the middle of the nineteenth century because horn was readily available and created a strong and waterproof container for gunpowder and, fortunately, a surface on which to record its history.”

Woodland buffalo east of the Appalachians were hunted to extinction by the end of the 17th century, making their horns difficult if not impossible to obtain for powder horns. Powder horns made from Woodland bison during the Colonial wars are unknown. Most of the Woodland bison horns are plain. Rare examples of these horns have a pattern of brass pins hammered into the butt plug of the horn. Within a circle of pins there is a design of pins. Based on Indian lore, Some researchers believe that the pattern of pins represent a constellation of stars visible on the night a baby was born, giving the child a lifetime sign.

Powder horns belonging to the white settlers during this period were made of cow horn. Most horns were plain, but many were inscribed with the name of the owner, the name of his location, like the “Niagara” horn (below), and many times even contained a map of the area.

Little historical information is available on the majority of trade beads discovered in archeological sites. The Hudson’s Bay Company has celebrated over three hundred years in North America, but the records on types and descriptions of trade beads, along with invoices, and sources of supply have not survived in the Hudson’s Bay archives. Today the company’s only examples of the Hudson’s Bay beads are in the Indian Arts and Crafts section of their museums.

Bead prices varied with location, demand, and how bad Indians wanted a particular bead. When trading for beaver pelts, the Hudson’s Bay Company used a standard value based on made beaver…a made beaver was stretched, dried, and ready for shipment. Records from early trading posts show a made beaver was worth: six Hudson’s Bay beads; three light blue Padre (Crow) beads; two larger transparent blue beads

Beads of this stage are distinctive. Most of them are small spherical and seed beads in a wide variety of colors, most of them monochrome. They are coated with a thin layer of crystal clear glass, giving them brilliance unequaled in any other stage.

Beads shaped like a grain of maize and made of brilliant transparent yellow and green crown glass, and seed beads of the same glass are common, but they are generally deeply corroded, with an opaque white chalky surface.

Large spherical dull black beads with spirals and guilloches enameled in yellow or white are another distinctive type limited to this stage.

These are blue beads from Bohemia with French Brass trade beads. The large bead at the center is a Dutch glass bead dating to 1650.

Glass beads are found in huge quantities. Most of them are cylindrical, the size and shape of belt wampum, in a variety of colors. A few polychrome spherical beads of the “Venetian” type occur, and the only necklaces made up entirely of this type come from sites of this age. The most spectacular bead type of all, a chevron bead the size of a pullet egg, is found only at this stage, but it is mainly represented by broken fragments scattered on village sites.

Native Americans along the eastern coast had their own beads. These beads were made from the “quahog” or hard-shell clam. The hard-clam furnished two colors of Wampum—white and purple. Only a small portion of the shell could be used to make the purple bead, resulting in its value being twice the value of the white bead. Wampum belts occur as grave offerings, and wampum beads are more abundant than at any other time.

With the introduction of metal tools to drill and work the clamshell, the beads became more uniform, about one-fourth inch in length and one-eighth inch in diameter. The Dutch and English colonists established factories to speed up the production of Wampum, thus becoming one of the earliest industries in America. John Campbell and his descendants in New Jersey made the bulk of wampum beads traded in this country. Quahog-shells were also sent to Europe to be made into Wampum and then returned to the colonies.

Beyond beads, the fur trade brought other decorative objects to the American Indian. Silver objects began to be traded during this period and continued throughout the fur trade era. Even today, silver is among the most sought after goods made by the American Indians.

These are examples of silver ear pendants and silver broaches traded by the French during the 1600’s. The ear pendant at the left of center was recovered in northwestern Georgia. The broach at right center is from an Iroquois town.

Silver gorgets traded during the 1600’s were prized possessions among the elite Native Americans.

Between 1640 and 1660 guns were abundant, arrowheads scarcely present; native pottery was obsolescent, brass kettles in normal use. Seal-handle spoons, apostle handle knives, rapiers, daggers, plate armor, specialized carpenter’s and other craft tools, and the first Dutch pottery pipes appear. Dutch and English white pottery pipe development is well documented, but even in this case we lack documentary material from earlier times and very few European pipes came into Indian possession before 1650.

European-made clay trade pipes like this one date between 1640 and 1660. (See our article on Clay Trade Pipes.)