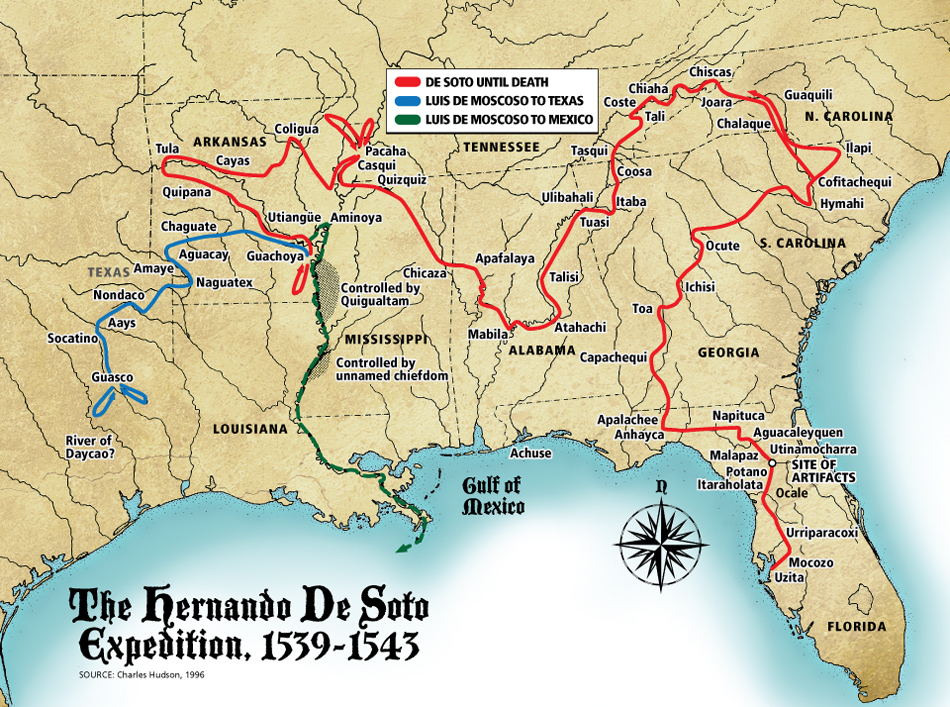

A hawk bell (also called hawking or hawk’s bell) is a small round object made of sheet brass or copper, originally used as part of falconry equipment in medieval Europe. Hawk bells were also brought to the American continents by early European explorers and colonizers in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries as potential trade goods. When they are found in Mississippian contexts in the southern United States, hawk bells are considered evidence for direct or indirect Mississippian contact with early European expeditions such as those by Hernando de Soto, Pánfilo de Naváez, or others.

The date of October 12, 1492 was very notable, for that was the day the ships of the initial Christopher Columbus voyage anchored off the island that was to be named San Salvador or as the local Taino Indians called it, Guanahani which would translate as Iguana. The expedition commander wrote in his log book that natives of the island rowed their canoes out to his vessels and brought parrots, cotton threads and spears as gifts for the foreigners. The Spaniards, in turn, gave the natives glass beads and small bells.

It took the Europeans over a hundred years to begin seriously exploring the large land mass that was near the island with the hope of acquiring gold and silver as they did in Mexico and South America. While they found no precious metals, they did find thousands of natives who knew how to grow and harvest corn and tobacco and knew how to kill and skin the many animals living in the region.

As the European explorers began to move inland from the coastal regions early in the seventeenth century AD, they discovered the natives were willing to exchange items they considered to be of little value, animal furs and skins and land, for the metal tools and shiny knickknacks the English, French and Spanish brought with them. A trading enterprise quickly arose as the intruders bartered brass and iron cooking pots and kettles, clay smoking pipes, iron axes and knives, black powder muskets and a multitude of small items the natives wanted for bodily decoration – glass and metal beads, conical shaped brass tinklers, sheet brass to be used for rolled tubular beads and arrowheads and the ubiquitous hawk bells.

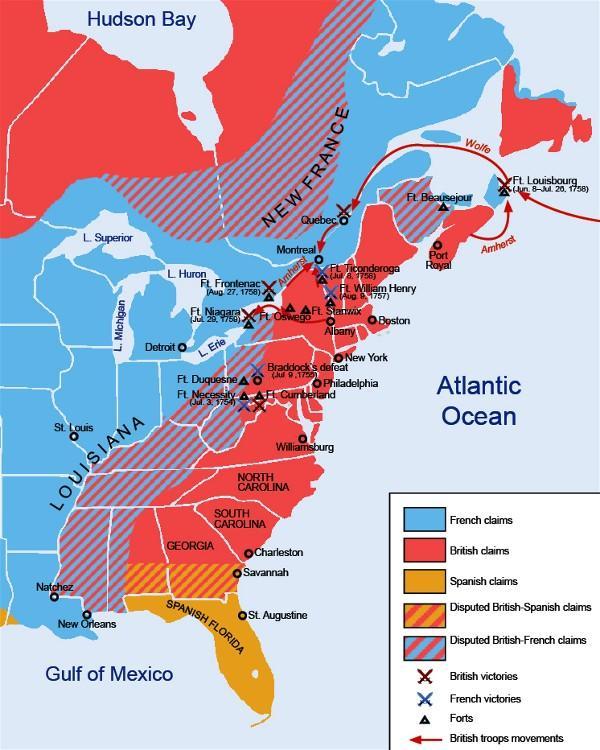

European trading companies came primarily from France, England and Spain.The French claimed Canada and their fur trade with the Indians (shown in blue) pushed across Canada, the Great Lake region and down the Mississippi and westward.British trade claimed most of the coastal areas of what is now the United States (shown in red) and the Hudson Bay area of Canada.The area claimed by Spain consisted of southern Georgia and Alabama and all of Florida (shown in gold).Areas where trade overlapped is shown in strips.Virtually every colonial settlement or fort within each area had some form of trading post and conducted trade with the Indians.Scattered among these areas, Dutch and other European traders sprang up to take advantage of the growing fur trade among the Native Americans.

The Native Americans tied these various bibelots to their limbs and/or wore them around their necks as well as being sewn onto clothing, especially when participating in ceremonial dances. The Creek burial near the trading post at Ocmulgee illustrates the use of Hawk Bells.

These ancient hawk bells are reasonably uniform in size and shape. They are usually round or spherical in shape and some were formed using flat sheet metal while the better ones were cast brass or occasionally bronze. They all have a small flange encircling the center of the bell, that is known to collectors as the equator flange, and most of these bells are around one inch in diameter though the sizes vary from less than a half inch for the smallest ones to more than 1 ½ inches for the largest. The raised equator flange denotes where the two halves of the bell were pressed together to make the sphere. Most have a narrow slit with a small hole at either end that extends around the lower half of the bell. The actual noise making part of the bell was called a clapper or ball or ringer and was usually made of iron in a either round or square shape and was placed in the bell before the two halves were swaged together. They all had a cast tang or bent wire at the top of the object with which the bell was attached to a falcon/tiercel or to a human and many of them still retain these fasteners today. The preponderance have two small holes near the attachment tang/wire which, along with the two lower half holes and slit, are there to allow the ringing bell to be heard for a greater distance.

Nearly all hawk bells (and horse bells) are plain brass without any further embellishment but some were engraved with a variety of lines and circles and other geometric shapes. These trade bells were apparently cheap and easy to make in Europe and since the American Indians liked the little clamorous objects, a great abundance of them was obviously brought into this country. Of course, like many perishable items that are lost or buried underground for a long period, they are reasonably few in number today except for the modern shiny reproductions of which there may be tens of thousands.

Some unscrupulous sellers of the new bells will bury them in fertilizer or attach them to a car battery so as to alter the color to a supposed ancient green patina- so beware of buying green hawk bells. An oddity of the old Indian bells is that since the internal clappers were usually made of iron, they corroded in the soil more quickly than the actual brass bells and are often entirely gone or can be seen through the slits and holes to be considerably rusted away. The records do not fully tell us when the Europeans began actually trading these hawk bells to the natives in large quantities but it possibly began as early as around AD 1625 and continued in the western regions of our country during the fur trading era that ended around 1850. During that two hundred plus year period, many thousands of these little noise makers were traded to the American natives and if you are really lucky and diligent in your artifact hunting, you just might be able to find, in a plowed agricultural field, one or maybe more than one, of these little Indian brass hawk bells.

This article was edited by Lloyd Schroder from an original article written by Jim Maus.