The Barnett Trade Gun

For more than three hundred years the name Barnett was prominent among gun makers in England. The North West Company, the Mackinaw Company, the American Fur Company, and the U.S. Indian Trade Office all distributed Barnett trade guns in the early nineteenth century. The Barnett Company producer more Northwest Indian trade guns than any other company.

(by O.Ned Eddins)

No gun in American history has had such widespread use as the Northwest trade gun. This smooth-bore, fowling piece, or single barrel shotgun, was used more than all the Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and Hawken riflers put together.

Firearms were brought to America by the first explorers, and some of these matchlocks fell into the hands of Indians. But for practical purposes, the Indian trade gun came about afterrthe introduction of the flintlock in 1620-1635. These early Dutch and English smooth bore guns established the pattern for the Northwest trade guns.

By the mid seventeen hundreds, the Indian trade gun was the most traded weapon in North America. The wide-spread use of Indian trade guns resulted in many names: the French called it the fusil, fusee, or fuke; the gun makers of England called it the Carolina musket; some traders and explorers, including Gen. William H. Ashley referred to it as the London fusil. The name also depended on its region of use; the gun was called the Hudson’s Bay fuke, the North West gun, or the Mackinaw gun. The first use of the term Northwest gun appears in the journal of John Long. An independent Montreal merchant, Long traderd with the Indians north of Lake Superior in 1777-1780.

From its beginning in 1670, the Hudson’s Bay Company traded guns to the Indians on a large scaler. By 1742, beaver pelts were valued at: one pelt for one pound of shot or three flints; four pelts for one pound of power; ten pelts for a pistol; twenty pelts for a trade gun.

The primary sourced of the Indian trade gun was factories in Birmingham and London, England. The gun makers in London charged that Birmingham turned out park-paling muskets for the American trade. The Birmingham manufacturers were often referred to as blood merchants and their factories blood houses by the London group. There are numerous accounts in journals of gun barrels blowing up when these trade guns were fired (Northwest Journal). There is no way to determine how many Indians and trader lost all or parts of their hands from these guns. Still, problems with the Indian trade gun were probably no higher than other Colonial guns of the period.

By the early eighteen hundreds, the trading companies had established rigid requirements for the Northwest guns. The full-stocked, smooth bore trade guns varied little in shape and style, but underwent changes in barrel lengths. By the late 1820’s, the 30 inch barrel had become popular. The overall length of a standard Northwest gun with a 30 inch barrel was 45.5 inches. A distinctive feature of these guns was the dragon or serpent shaped side plate. Most Indians would not trade for a gun that did not have the serpent plate. Hansen states that the earliest record of the Hudson’s Bay gun with its distinctive dragon ornament is dated 1805.

Northwest trade guns, each with a different serpent side plate.

(Tom Richards collection, Hotherm, 2007)

After 1800, almost all the Indian trade guns were supplied with blue barrels, brown-varnished stocks, and bright polished locks. These guns were stamped below the pan with a large sitting fox-like animal facing right and enclosed in a circle of 0.4 inch diameter. These guns carried the brass serpent side plate and an oversized trigger guard for use with mittens. Despite the majority of the Indian trader guns being made in Birmingham, England the majority of the Birmingham gun makers stamped “London” on the top near the breech.

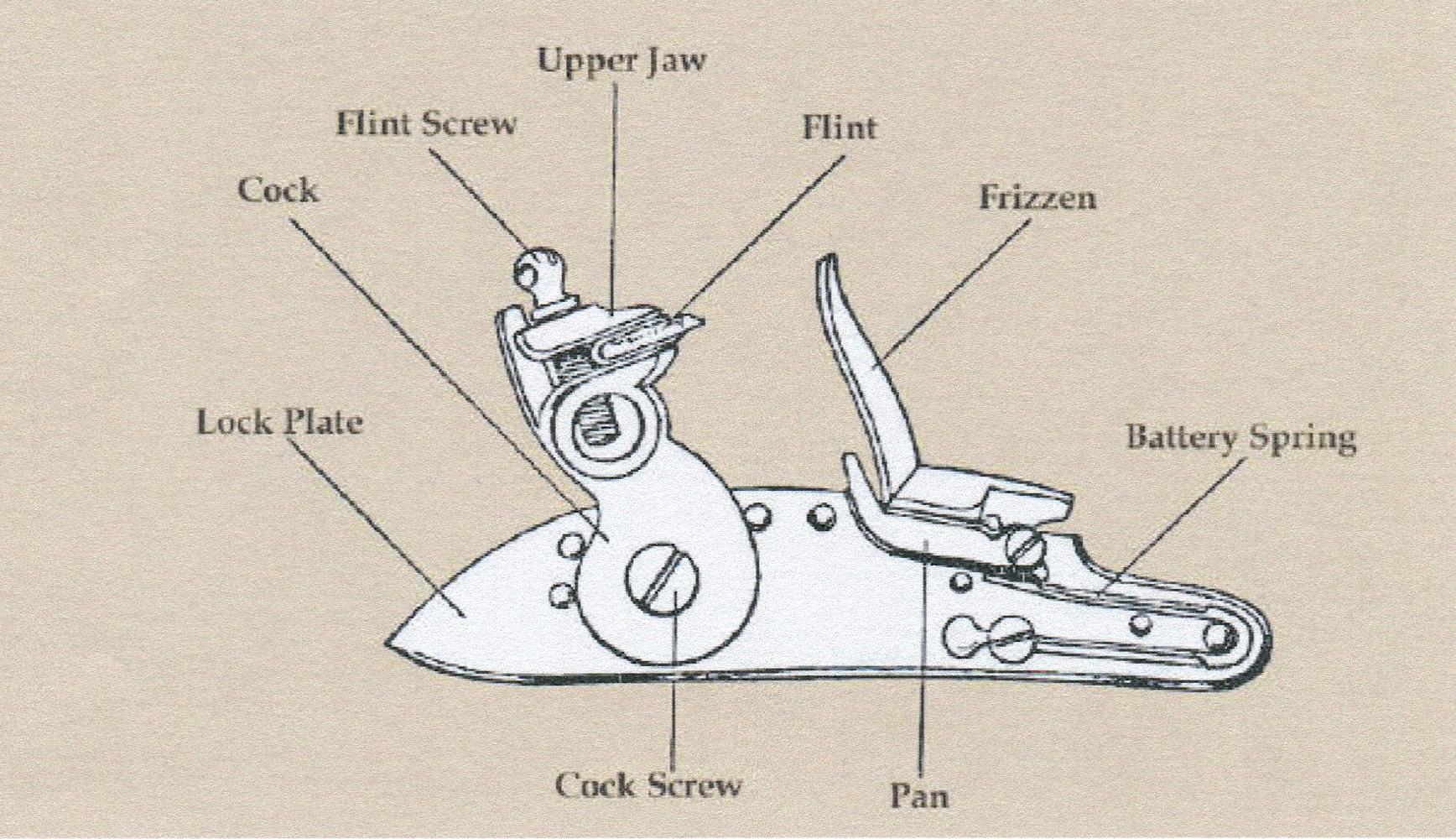

Rarely is a gun possessed by a Native American seen in tact. Those that are in tact have been handed down through generations. Most arms recoveries are metallic fragments of the original. The gun works pictured here may help you identify your findings.

Historically, trade guns were specifically patterned firearms sold or traded to indigenous People of any given geographical area by a fur or a land company. Settlers, trappers, and hunters recognize the versatility of this inexpensive game getter also but it was specifically designed for the Native Americans of North America.

The trade gun’s light weight and smaller caliber ball, then the military arms of the day, lends itself to being carried farther in country for the long hunts of the time.

The Le Fusil De Chasse is an equally distinguishable flintlock firearm, with it’s graceful drop at the butt stock and French style iron hardware. This handsome and rugged firearm served the French People and their Native American allies from roughly 1696 to well after the French and Indian War.

More expensive to manufacture and sell than it’s English contemporary, the Fusil De Chasse was preferred by many tribes and people; it’s style was even copied by at least one English gunmaker to try and capitalize on the French gun’s reputation of ruggedness and dependability.

Mounted in brass, this long arm would be considered a French type “C” or “D” trade gun depending on the style of the hardware.

Perhaps two of the most notable locations for the Indian Police Agency were the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation and activity surrounding the surrender of the famed Geronimo and the battle at Wounded Knee near the homeland of Sitting Bull.

The San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation, in southeastern Arizona, was established in 1871 as a reservation for the Chiricahua Apache tribe. It was referred to by some as “Hell’s Forty Acres,” due to a myriad of dismal health and environmental conditions. After the Chiricahuan Apache were deported east to Florida in 1886, San Carlos became the reservation for various other relocated Apachean-speaking groups.

The Wounded Knee Massacre happened on December 29, 1890, near Wounded Knee Creek (Lakota:Čhaŋkpé Ópi Wakpála) on the Lakota Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. On the day before, a detachment of the U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment, commanded by Major Samuel M. Whitside intercepted Spotted Elk’s (Big Foot) band of Miniconjou Lakota and 38 Hunkpapa Lakota near Porcupine Butte and escorted them 5 miles westward (8 km) to Wounded Knee Creek where they made camp.

The rest of the 7th Cavalry Regiment arrived led by Colonel James Forsyth and surrounded the encampment supported by four Hotchkiss guns.

On the morning of December 29, the troops went into the camp to disarm the Lakota. One version of events claims that during the process of disarming the Lakota, a deaf tribesman named Black Coyote was reluctant to give up his rifle claiming he had paid a lot for it. A scuffle over Black Coyote’s rifle escalated and a shot was fired which resulted in the 7th Cavalry opening firing indiscriminately from all sides, killing men, women, and children, as well as some of their own fellow troopers. Those few Lakota warriors who still had weapons began shooting back at the attacking troopers, who quickly suppressed the Lakota fire. The surviving Lakota fled, but U.S. cavalrymen pursued and killed many who were unarmed.

By the time it was over, at least 150 men, women, and children of the Lakota Sioux had been killed and 51 wounded (4 men, 47 women and children, some of whom died later); some estimates placed the number of dead at 300. Twenty-five troopers also died, and thirty-nine were wounded (6 of the wounded would also die). It is believed that many were the victims of friendly fire, as the shooting took place at close range in chaotic conditions.

The site has been designated a National Historic Landmark.