For more than one hundred years archaeologists have debated and held opinions concerning the use of these finely worked objects. Some have believed them to be fishing weights while others including Dr. James Ford believed them to be bolas. In 2011, Carl P. Lipo and Timothy D. Hunt conducted a study on plummets from the Poverty Point site for the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Some 2700 plummets have been recovered from the Poverty Point site. Two forms emerged, one perforated and one grooved. The beautifully shaped plummets made of hematite took both forms and probably made their first appearance during the Late Archaic period between 1000 and 2,000 B.C. The later, roughly shaped and grooved plummets from the site seem to date with the Cole’s Creek sites from A.D. 700 to 1100. The plummets from this site are found along the Macon Ridge (pronounced Mason Ridge), located along the lower Mississippi River Valley from Louisiana to Arkansas and Mississippi.

Lipo and Hunt sought to discover the use for these objects, which are often seen as decorative charms. They measured the length, width and weight of each of the 138 examples used in their study. They also studied the records of their recovery from sites along the Macon Ridge. Their findings from measurement saw a consistency in width, but not necessarily in length. Their search of sites found plummets predominately in domestic sites. The fishing weight application would have produced these “weights” in streams, but none were found in that context. The snare application would have left examples in areas of hunting, but, again, none were found. The charm idea, again, left no examples in burial contexts that were consistent with the wearing of charms; evidence that is common to hawk bells and beads.

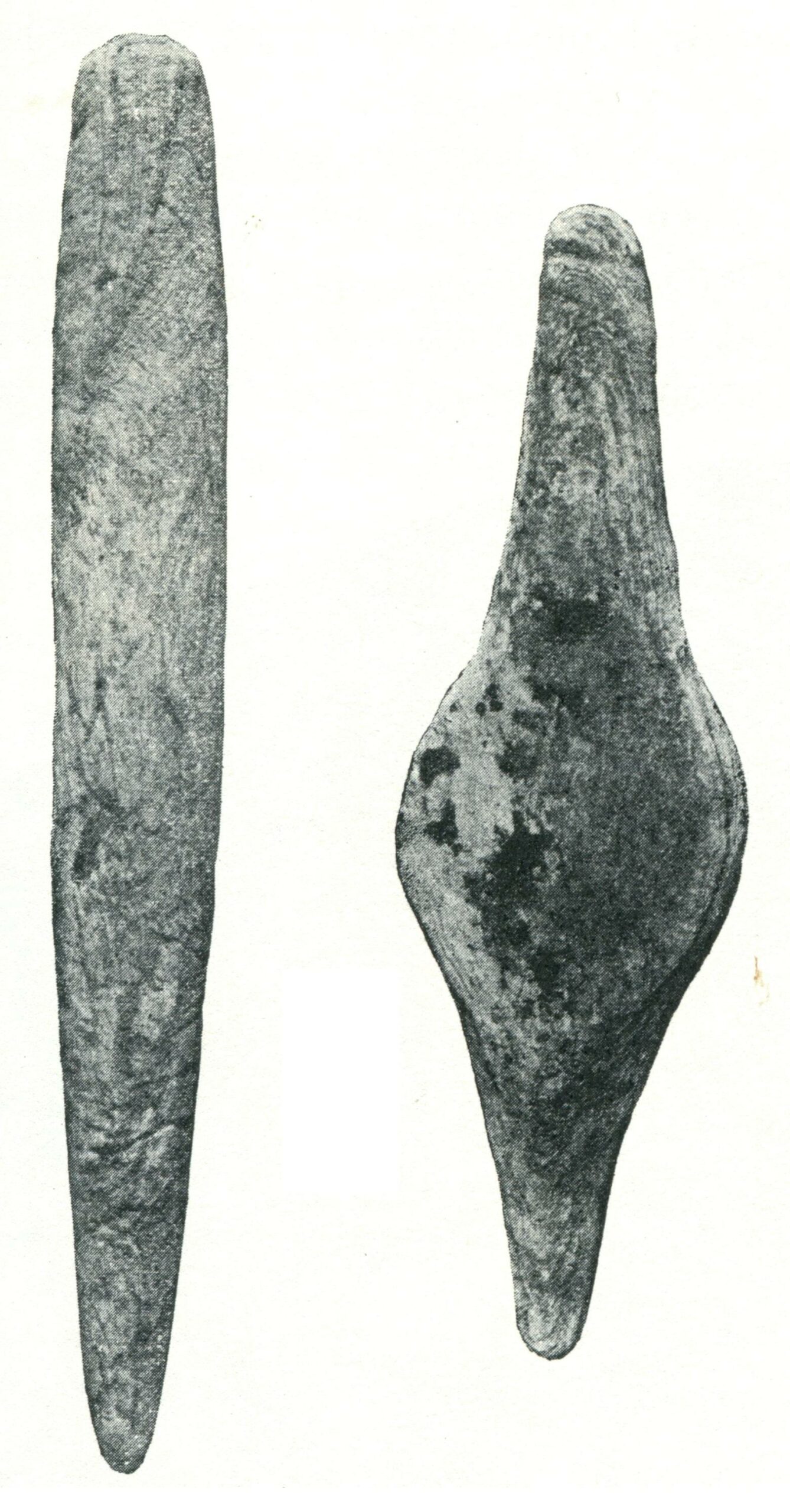

Plummets like these from Mississippi (left) and Florida (right) would have inspired the belief that they were charms.

As Lipo and Hunt continued to search for a viable application that fit into the domestic site use, it occurred to them that the regularity of the width and weight of plummets as well as the timing of their appearance fit the development of the weighted weaving loom. The warp threads were held taunt by the weights while the weft threads were woven in and out of the warp cords with the use of a shuttle. Their solution seems plausible as it fits the domestic context. The later disappearance of plummets during the Late Woodland and Mississippian periods also fit the loom application as fixed-frame weaving came into use.

My survey of 200 illustrated examples recovered by C.B. Moore during his excavations throughout Florida was done to compare their use in Florida with the conclusion drawn by Lipo and Hunt. Of the 200 examples recovered and illustrated by Moore in Florida, 100 came from mounds near Crystal River in Citrus County, Florida. The Ten Thousand Island area of Lee and Monroe Counties yielded 47 examples; 8 from Goodland Point, 18 from various sites within the Ten Thousand Island area, 11 from the Key Marco site, and 10 from Cholokoskee Key in Lee County. The remaining 53 examples were recovered from various sites to be discussed below.

Seven examples were recovered from mounds that also contained European trade items. The Tavares Mound in Lake County contained 4 examples along with glass trade beads and the Little Manatee Mound in Hillsborough County contained 7 examples along with Historic period Safety Harbor pottery and glass beads of the type left by Hernando DeSoto.

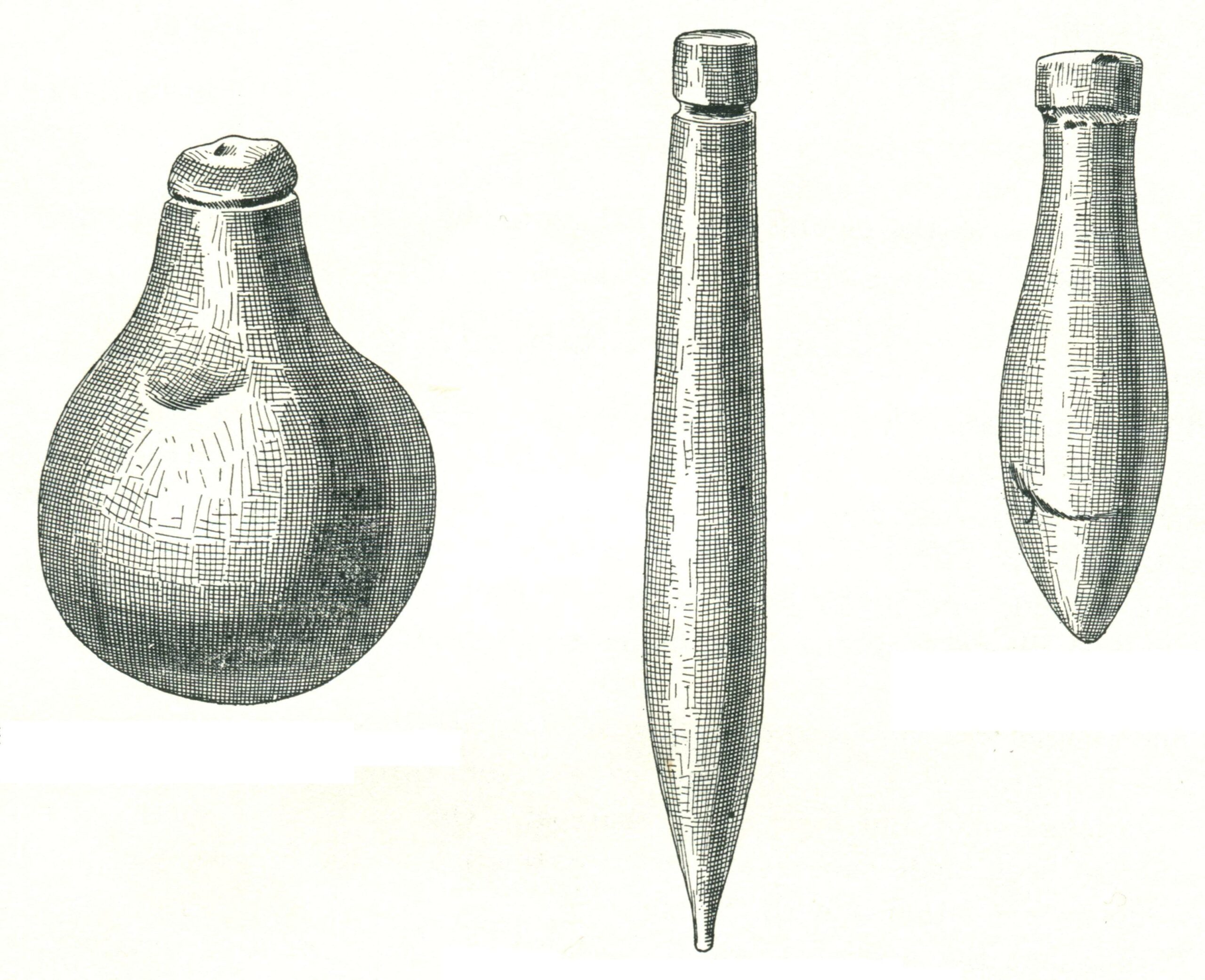

Spanish explorer Panfilo de Narvaez and Hernando DeSoto traded these Nueva Cadiz beads (left) to the Indians of Florida in 1527 and in 1539. The plummets from this Historic period site are shown at the center. The effigy plummet from the Little Manatee Mound is shown at the right. These “plummets” may actually have served as decorative pendants during the Historic period.

The remaining 193 examples come from unidentifiable contexts or are believed to date to the Middle Woodland period given the associated pottery types contained within each site. Associated pottery types included Deptford Check Stamped, Swift Creek Complicated Stamped, St. Johns Pinched, Punctated, Cord Marked and Plain and Dunns Creek Red pottery, Weeden Island, Carrabelle Punctated and Papys Bayou pottery, Markham pottery, Crystal River Incised and Painted, and Franklin Plain pottery, Oklawaha Plain pottery, and Pasco Incised pottery. The Pithlochascootie River Mound in Pasco County contained primarily Middle Woodland period pottery, but also contained a Mississippian period Englewood Incised vessel that was probably an intrusive burial.

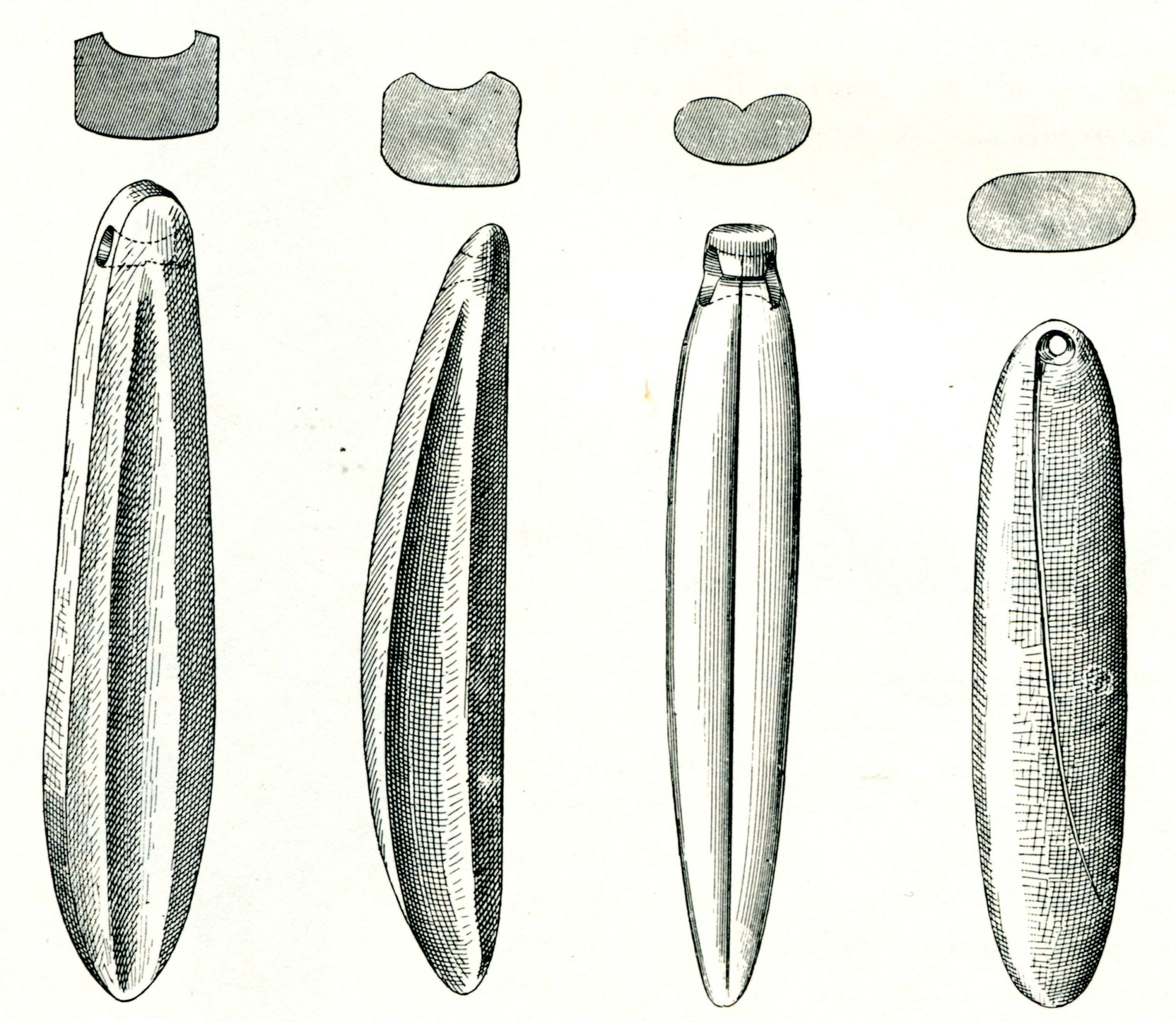

The material from which the plummets were made included a variety of stone, shell, teeth, copper, coral, crystal, bone, and, in one case, pottery. Each type of material generated its own size variation. For the purpose of this discussion, the following description of plummet shapes has been used. More appropriate descriptions may already be in use.

Shell examples averaged a length of 3.2 inches by .7 inches in width with a maximum length of 9.1 inches and a maximum width of 1.8 inches. Plummets of various kinds of stone numbered 101 and averaged 2.9 inches in length and 1 inch in width with a maximum length of 8.9 inches and a maximum width of 1.4 inches. Quartz crystal plummets averaged 3.1 inches in length and 1.1 inches in width with a maximum of 4 inches in length and 1.6 inches in width. The 12 copper plummets from Crystal River averaged 4.5 inches in length and .7 inches in width with a maximum length of 8.25 inches and a maximum width of 1.25 inches.

The explorations of C.B. Moore focused on mound structures. Domestic sites were excluded except for the shell fields at Key Marco, thus the majority of the plummets included in this study were recovered from a mortuary context. The examples used in this study came from 23 sites explored by Moore. Even so, 40.5 percent of the examples were recovered in the mounds at separate locations from the immediate context of human remains and 54 percent were in a burial context with the remaining 4.5 percent of the examples in unknown contexts but within the mounds. What became immediately evident was the presence of shuttle-like, cigar-shaped objects of shell, stone and bone within the mound at Grant Mound, Gamble Mound, Chokoloskee Key, Crystal River, and Key Marco. Many of these were recovered from a context that was separate from human remains, but were recovered from the mound sand.

The four examples on the left, two made of igneous rock and two of sedimentary rock, are from the Tavares Mound in Lake County, Florida that also contained Nueva Cadiz beads and portions of a looking glass, a perforated plummet of igneous rock, a pear shaped plummet of igneous rock, two pear shaped plummets of shell and nine ellipsoidal or spindle shaped plummets of shell. The illustrated pottery from this mound belonged to the Middle Woodland period and consisted of St. Johns and Weeden Island pottery, which may indicate that the Historic period burial containing the beads was a later addition to an existing mound. The pendent on the right, made of an exotic hardstone material, is from the Helena Mound, also located in Lake County. This pendent, like those of the Tavares Mound, were in direct association with human remains and may indicate their use as pendants rather than plummets.

The plummets pictured above are from the Goodland Point Mound in Lee County, Florida. It should be noted that, while not classified as a “plummet,” the doughnut shaped object in the lower right corner of the picture is also a known loom weight form. Also recovered from the site was a 13.25 inch claystone pin that was squared off at each end and may have served as a shuttle (right).

The Goodland Point site also produced the only pottery plummet (left center) recovered by Moore in Florida. The site contained a large number of shell tools and drinking cups as might be expected in southern Florida. One of two plummets recovered by Moore to have a central horizontal groove and another with a central perforation were at this site. The bone shuttle (left) recovered at Goodland gives strong evidence of a weaving industry at this site as well.

One unusual plummet from the Goodland Point site that was illustrated by Moore was incised on all sides.

Ten plummets in all were recovered from the Gamble Mound in Marion County, Florida. The plummets were made from a variety of materials including chert, slate, fossil bone, sedimentary and igneous rock, limestone and quartz. Moore noted that bitumen had been used in the suspension of grooved plummets, but that it had not been necessary with perforated examples.

Bitumen is a black, sticky semisolid substance of a naturally occurring petroleum such as oil sand or tree sap. This substance was often formed into a ball and transported on a stick (note the hole) and could be returned to a softened state by heating the mass.

Pottery types recovered from the mound included Deptford Check Stamped and Plain pottery and several Dunns Creek Red basins that had been “killed” by breaking the bottoms out. One interesting implement recovered from the mound was a 6 inch section of a Florida Lithic Dagger or mortuary blade. Several of these blades were interred with human remains at the Royce Mound and other Deptford period sites in Florida. The finely worked Lithic Dagger from Steamboat Springs in Alachua County (above) is of the type recovered at the Gamble Mound. The largest blade of this type known measured 14.5 inches in length and 4.5 inches in width, but most measured between 6 and 10 inches long.

The Chokoloskee Key site in Monroe County Florida yielded ten plummets made from a bear tooth, a limestone effigy of a bear tooth, coral, limestone, shell, and igneous rock. The site also contained a five inch argillite pin that may have served as a shuttle. A rare, unbroken Markham pottery drinking cup (right) was also recovered from the site. Markham pottery dates between 400 B.C and A.D. 400.

The mound at Gigger Point contained just two plummets, one of which was not illustrated by Moore. With the plummet, however was a 4.75 inch “cigar-shaped” object of shell (far left). Again, these objects I believe are shuttles. The mound also contained an “arrowhead” made of sheet mica. These mica cutouts (right center) are from Georgia’s Etowah site, but illustrate the use of this sought after trade item during the Middle Woodland period. The beautiful Carrabelle Punctated vessel (far right) was also recovered from the Gigger Point mound.

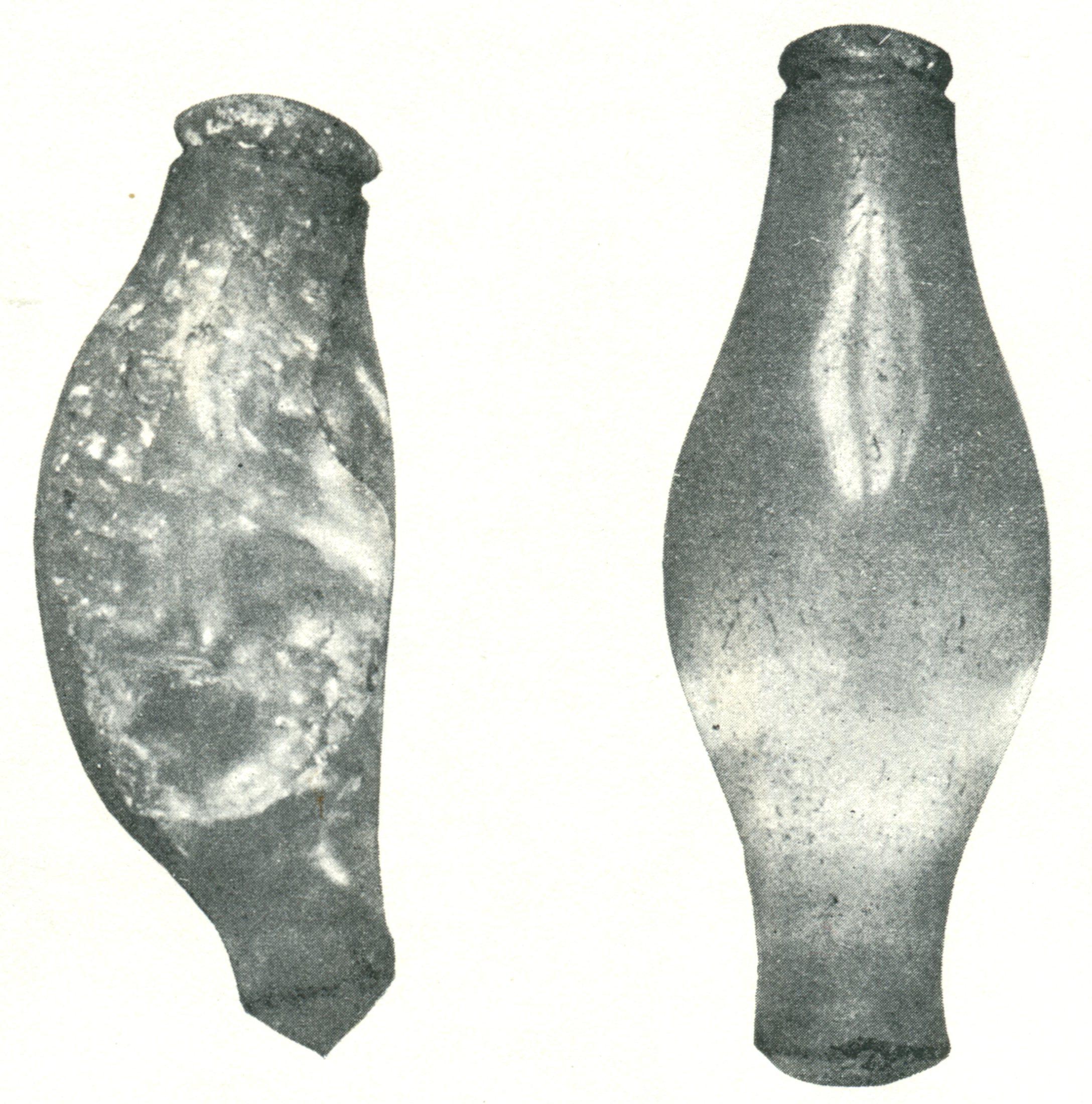

The Crystal River site produced a total of 167 plummets, 100 of which were illustrated by C.B. Moore. The materials in making the plummets included shell (left), various kinds of stone (right), crystal (below) and copper.

The four crystal plummets may in fact have been intended as decorative charms like the beads and pendants above them, but there is little doubt regarding the intended use of the two quartz crystal plummets to the right.

The Crystal River Mounds contained the only copper plummets encountered by Moore in Florida. The plummets measure between 1.3 and 8.25 inches in length and .5 and 1.25 inches in width.

In addition to the ten stone plummets pictured above that were recovered in a single burial is this random collection of forty-five stone plummets from Crystal River.

In this additional grouping of stone plummets above from Crystal River (above left), notice the plummet at the upper left and its similarity to the copper plummet pictured above (top row center). The shuttle-like objects (above right) are also from Crystal River and are perhaps a further indication of the plummet use as loom weights

The Key Marco site yielded an untold number of plummets. Moore noted that Mr. Collier of Key Marco had “several hundred” plummets in his possession from the site. Moore illustrated eleven examples, most of which were made of limestone or shell.

An interestingly designed plummet from Grant Mound in Duval County, Florida and one from the Chassahowitzka River mound in Citrus County. A very similar example came from Tick Island. Similar forms like these may indicate trade and communication links between sites during Florida’s Middle Woodland period.

Moore illustrated only six plummets from the Tick Island site; however, the excavations done by Ripley P. Bullen in 1961 yielded an additional sixty-two examples that were illustrated in the Florida Anthropologist, volume 31, number 4, part 2 in 1978. The Tick Island site in Volusia County, Florida was a key trade site along northeast Florida’s St. Johns region.

Two examples from the Hitchens Creek Mound in Volusia County (left) demonstrate a slightly different hafting technique with a flange replacing the more typical groove in Florida plummets. The Mulberry Creek mound in Orange County contained only one plummet and a familiar form of bone shuttle (center). Surprisingly, the Mt. Royal mound, known for its copper artifacts and its long duration, contained only one plummet (center right) made of quartz. The Pithlochascootie River Mound in Pasco County contained only two plummets as well. These four northeastern and central Florida sites may demonstrate a trend toward the development of weaving centers at places like Tick Island and Crystal River during the Middle Woodland period in peninsular Florida with a dependence on trade in the smaller locations.

The investigations of C.B. Moore into the many Weeden Island and other Middle Woodland sites of northwestern Florida does not seem to have yielded much in the way of plummets or evidence of the presence of weighted looms. The only plummet examples illustrated from this region were from the Green Point mound (top) and the Yent mound (bottom). These were important mound sites, yet the evidence for weaving was scarce. The excavations of Gordon Willey in the Middle Woodland sites of the region were conducted largely in middens and focused on pottery type development and stated little regarding other artifact types contained in the sites. The total absence of the hematite, Poverty Point- type plummets from this region suggests that the trade for this site, at least regarding plummets, was restricted to the Macon Ridge area along the lower Mississippi River basin.

Lipo and Hunt had concluded that there was a surge in the textile weaving industry at the Poverty Point site during the Late Archaic and Woodland periods. It appears that there must have been a similar surge at Key Marco and Crystal River and with other smaller sites across peninsular Florida during the Middle Woodland period. The inclusion of plummets in a burial context during this period may also be an indication of the advent of fixed frame weaving, making the plummets obsolete and thus fitting material for mortuary purposes. C.B. Moore had noted the practice by Native Americans of placing broken, unfinished, or inferior materials in burials across the Southeast and obsolete plummets, many of which were beautifully made, would have fit nicely into this scenario.