No one knows for sure who made the first clay pipes. The idea of smoking tobacco came from the American Indian, who had long fashioned their own clay pipes. These, no doubt served as a model for later pipe development. By 1558 tobacco smoking had been introduced to Europe. There is little doubt that the earliest pipes came from England. The Spanish had observed the Indians off Florida’s coastline smoking cigar-like rolled tobacco leaves in 1493 and had eventually adapted that form of smoking for themselves. The English pipe-making industry grew quickly to satisfy the growing demand of people, including women and children, to take up the art of “tobacco drinking” as it was then called.

Pictured above is a British pipe mold that dates to the early 1600’s. It is a part of the collection of Steve Beasley, who purchased it while in England.

The basic form of the pipe has changed little over the long history of pipe smoking, however there have been notable variations in pipe styles effecting the size of the bowl and the length of the stem. Many of these variations were the result of fashion, but many were the result of the growing skills of pipe makers. The size of the bowl was often effected by the cost and availability of tobacco.

The effects of English pipe manufacture eventually came full circle back to the American Indians through the fur trade sometime early in the 1600’s. Excavations at Fort Union, located along the upper Missouri River (1828-1867), yielded some 10,000 clay pipe fragments. The Indians were egger to trade with whites for the European goods. These trade relationships greatly reduced the Indian’s reliance on their own crafts as clay trade pipes, iron tools, and weapons began to appear in their villages.

1580 – 1610: By 1573 the first written description of clay pipes referred to them as being shaped like a ladell. These early pipes are sometimes referred to as “belly pipes” because of the pot-belly or barrel shape of their bowl. The spur or platform at the bottom of the bowl was hart shape. The stem was fairly short, only measuring 4 to 6 inches. The spur allowed the pipe to rest upright on a table.

1610 – 1640: This period saw the development of a flat base and a true spur upon which to rest the pipe. The diameter of the bowl had increased only about 3/8 inch and there was no noticeable increase in the length of the stem.

1640-1660: The size of the bowl increased slightly during this period and stems increased to between 10 and 14 inches. The spur became rounded, perhaps to allow the bowl to rest on a table top during smoking without marring the finish of the table. A few elaborately decorated pipes appeared during the first half of the century, mostly of Dutch origin. Decorations were stamped, incised by hand, or molded in relief on both bowl and stem. One of the most notable designs was Jonah about to be swallowed by a serpent, perhaps depicting King James I who tried diligently to stamp out smoking.

1660 – 1680: There is a noticeable size increase during this period. After 1640 pipe styles remain basically the same with some regional variations in England. Except for the occasional maker’s mark (the pipe pictured is Dutch-1670-1700), the pipes for the seventeenth century were plain.

1660 – 1680: One such variation was the West Country style pipe that featured a curved bowl that lost much of its “barrel” look. This was the first long-bowl pipe that would gain in popularity through the end of the century.

1680 – 1710: The long-bowl became firmly established during this period. A milled or plain ring at the top of the bowl is present on many pipes from the later half of the century. Towards the end of the seventeenth century the inside diameter of the bowl was about 1/2 inch and the bore diameter of the stem was between 3/32 to 1/8 inch. Generally, the older the pipe, the larger the bore of the stem. Most stems were straight, but some tended to curve either up or down. This was more a result of firing than from design.

For those who enjoy collecting clay trade pipes, we have added additional notes about maker’s marks and stem stamping based on the work of Robert F. Marx at the site of the sunken city of Port Royal, Jamaica in 1968. The study is focused on English made pipes, but provides a system of dating between 1680 and the mid 19th century.

1700 – 1770: One of the most striking features of pipe development during this period is that the top of the bowl became parallel with the stem. During the mid eighteenth century, extra-long pipe stems became fashionable, measuring between 18 and 24 inches in length with a stem bore averaging 3/32 inchs. These were first called aldermen pipes, but later were referred to as straws. This is the first time a style of pipe was actually given a specific name during their period of use. These and some short, plain pipes became the order of the day during the 1700’s. There were some pipes decorated with leaf forms along the seams or a coat of arms of a city, company, or feathers of the Prince of Whales (the above pipe has (PW) stamped on it and the coat of arms) during the early part of the century. The second pictured pipe has leaf forms along the stem. It is unknown if the male figure is that of the Prince of Wales, but the reverse side has a female figure. These had high polish and craftsmanship. By 1750 masonic emblems were added.

1770 – 1820: Pipes were being made with greater accuracy, a smoother finish, and a higher degree of brittleness. The wall of the bowl became thinner and the stem more slender. Early eighteenth century pipes favored a flat spur and some were produced with no spur at all. These were especially popular in North America between 1720 and 1820 and are believed to be distributed by Bristol pipe makers.

1810 – 1840: Pipe bowls continued to be long during this period with rims that are parallel with the stem. Spurs were long and pointed. This change in spur forms was essentially the singular variation during this entire period. The important event during this period was political. In 1830, the Indian Removal Act swept across Georgia, removing Indian populations to the west. Pipes of this period could presumably be the last pipes used by Native Americans in Georgia. Pipes from subsequent periods would relate to white colonial populations.

1850 – 1910: After 1850 the very long “yard of clay” pipes were introduced. As the name implies, these pipes measured about 36 inches long. Their length must have made them fairly impractical and they are viewed as a passing phase. To assist the smoker in handling this long pipe, the stems were either marked with a label or twisted at their balance point. Later in the century these long pipes became more popular and were called churchwardens. Charles Dickens is credited for the name or at least for its perpetuation. Shorter versions, called short churchwardens were eventually marketed.

In Virginia the Pamplin Pipe Factory, located in Pamplin City, Appomattox County, VA. is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Its history dates back to the Appomatucks Indians and their cottage industry of clay pipes. The first major industry in Appomattox was the Pamplin Smoking Pipe Manufacturing Company. Established in 1878, this factory manufactured clay pipes for over 70 years before closing in 1951.

The Akron Smoking Pipe Company operated in Mogadore, Summit County, Ohio from 1885 to 1895. It also had branch factories in Point Pleasant, Ohio and Hampton, Virginia as late as 1908. These are reed stemmed pipes. The maker’s marks for American made pipes of this type are generally in the bottom of the bowl. English made Red Clay pipes that conform more to the white clay pipe styles seem to have most of their markings along the stem. Marx illustrated the English Red Clay styles below with a listing of their maker markings.

The second half of the century saw pipes become a form of advertisement for everything from public houses to sports. These were sold under the category of fancy clays. Most pipes had designs on the sides of the bowls, but some pipes were made in the shape of their subject from the naughty to chamber pots. No less that nine presidential candidates appeared on pipes from George Washington to Zachary Taylor. The scalloped pipe pictured above dates to 1870. Competition from beautifully carved meerschaum pipes and their comfortable amber mouthpieces, brought about change as vulcanite mouthpieces were fitted to stems or the stem was given a sharp bend near the end after molding. Imitations of the calabash and briar pipes were also made near the end of the century. (Pipe form #13 is a Dutch form that was copied by some English pipe makers.)

a. The Angler’s pipe is English b. The horn pipe is also of English origin, both date to the late 1800’s

a. Football pipes were either a foot and ball as the spur or an action scene on the bowl. b. The skull pipe is one of many shapes that carried special themes or advertisements. c. This example may be a football scene or one of the more risque English pipes made between 1690 and 1700 and seems to correspond to the Marx #140 makers mark style (below).

1860 – 1930: The trend of pipe makers to copy the briar pipes continued from the prior period. The spur was lost and the bowl was plain. The common man enjoyed a simple short stemmed pipe, often breaking off the longer stem. Many referred to these shortened versions as “nose warmers.” By 1914 the pipe making industry was all but lost. The pipe pictured above had maintained the spur and represented the RAOB society. It was likely made by the Pollock company of Manchester, England between 1900 and 1920. Many of these pipes had a buffalo head on them. This example had only the horns and hair. The second pipe pictured here conforms more to the type described as the trend. By 1930 pipes were manufactured for children to blow bubbles, only later to be replaced by plastic pipes by the 1950’s.

Clearly, this wooden pipe is not part of the clay pipe history, or is it? It may be the result of the unavailability of a clay pipe that spawned the need to fashion this wooden pipe, using the clay pipe as a model. The form suggests a copy that may belong to the late 1800’s. This one-of-a-kind recovery was made in a back yard in Baldwin County, Georgia.

By Heather Coleman

In the archaeological studies carried out on clay pipes (and believe me there are many!) mathematical formula’s have been applied to explore the possibilities of dating them by the size of the hole in the stem. While these have been proven to work fairly well where large groups (usually dozens-hundreds), it isn’t always true. It is not always possible to date a random piece of broken stem by the size of the hole because there are many other factors that come into play. The thickness of the stem, surface finish and porosity, alignment of sides, tool marks, junction at base of the bowl etc. are just some of these. However, the larger thick more weathered pipe stems that are often found with a bigger hole in the middle tend to be earlier from the 17th-18th Centuries, whereas thinner stems with even sides, smoother surfaces and much smaller holes tend to be from the 19th Century. It is worth mentioning also here that Dutch pipes of the 18th Century have very long narrow stems with smaller holes whereas English pipes of the same period tend to have larger holes so this is another thing to be considered according to where finds are made. During the Victorian period some pipes were made in such a hurry and without thought for the smoker that the hole in the stem was not always practical or even joined with the bowl.

In my experience as a clay pipe maker of replica’s for all periods I sometimes simply take the nearest piece of wire to hand according to the length or style of the pipe I am making. I am sure pipe makers of past times did the same, especially if taking on apprentices. The Manchester firm of Pollocks even used umbrella spokes at one time! Very often smoker’s prefer a hole that allows them to drink or sip tobacco rather than having to suck really hard through a hole that keeps blocking up.

by Robert F. Marx

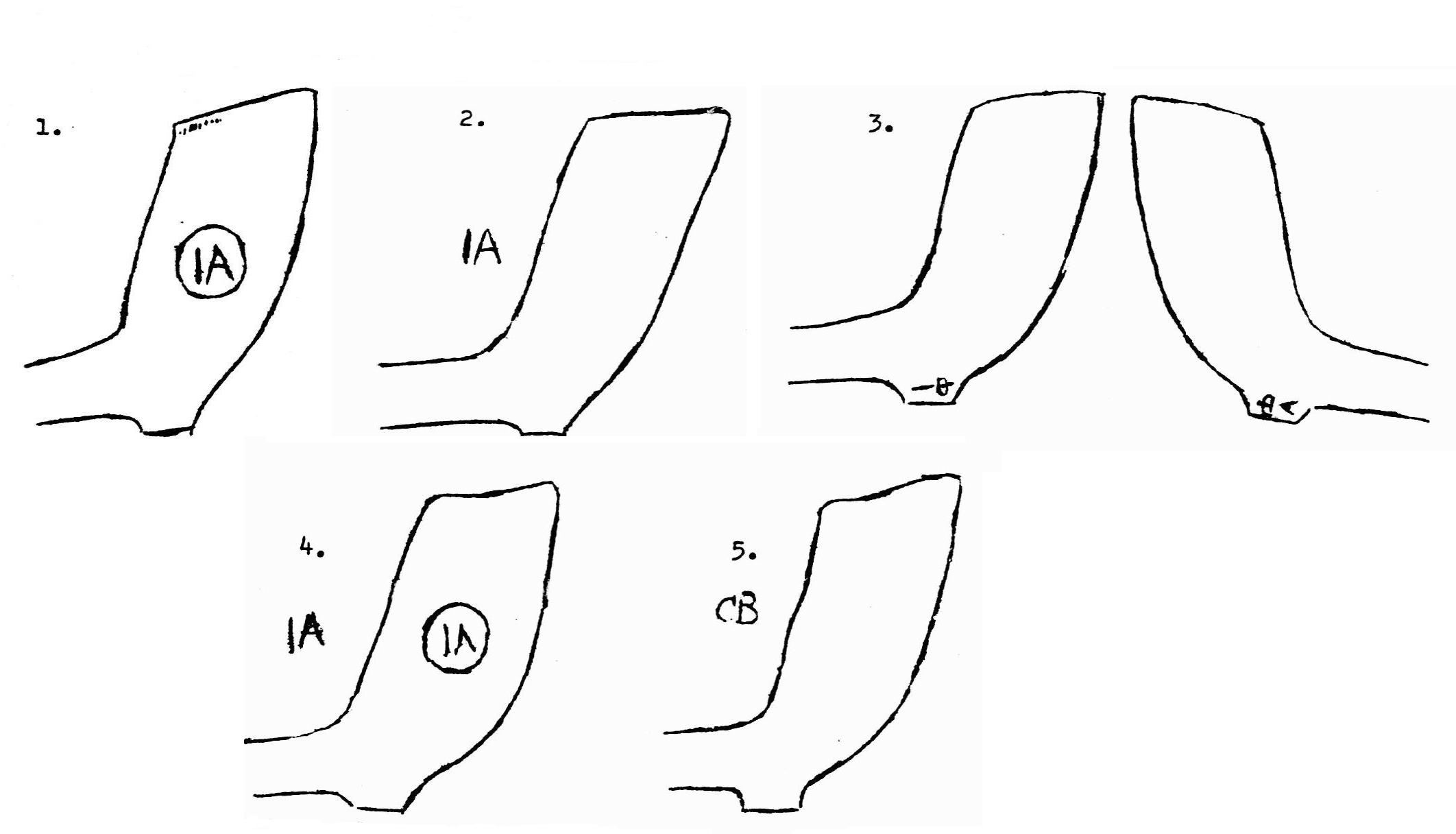

1. IA embossed on right hand side of bowl c.1700-40. Many different possible Bristol makers.

2. IA Incised – center of bowl. c.1700-40. Many different possible Bristol makers.

3. IA embossed on right and left side of heel. c.1700-40. Many different possible Bristol makers.

4. IA Incised on center of bowl. IA Embossed on R.H.S. of bowl. c.1700-40. Many different possible Bristol makers.

5. CB Incised on center of bowl. C. 1680-1730. Charles Buckley, Bristol, Freeman 1713, Polls 1722

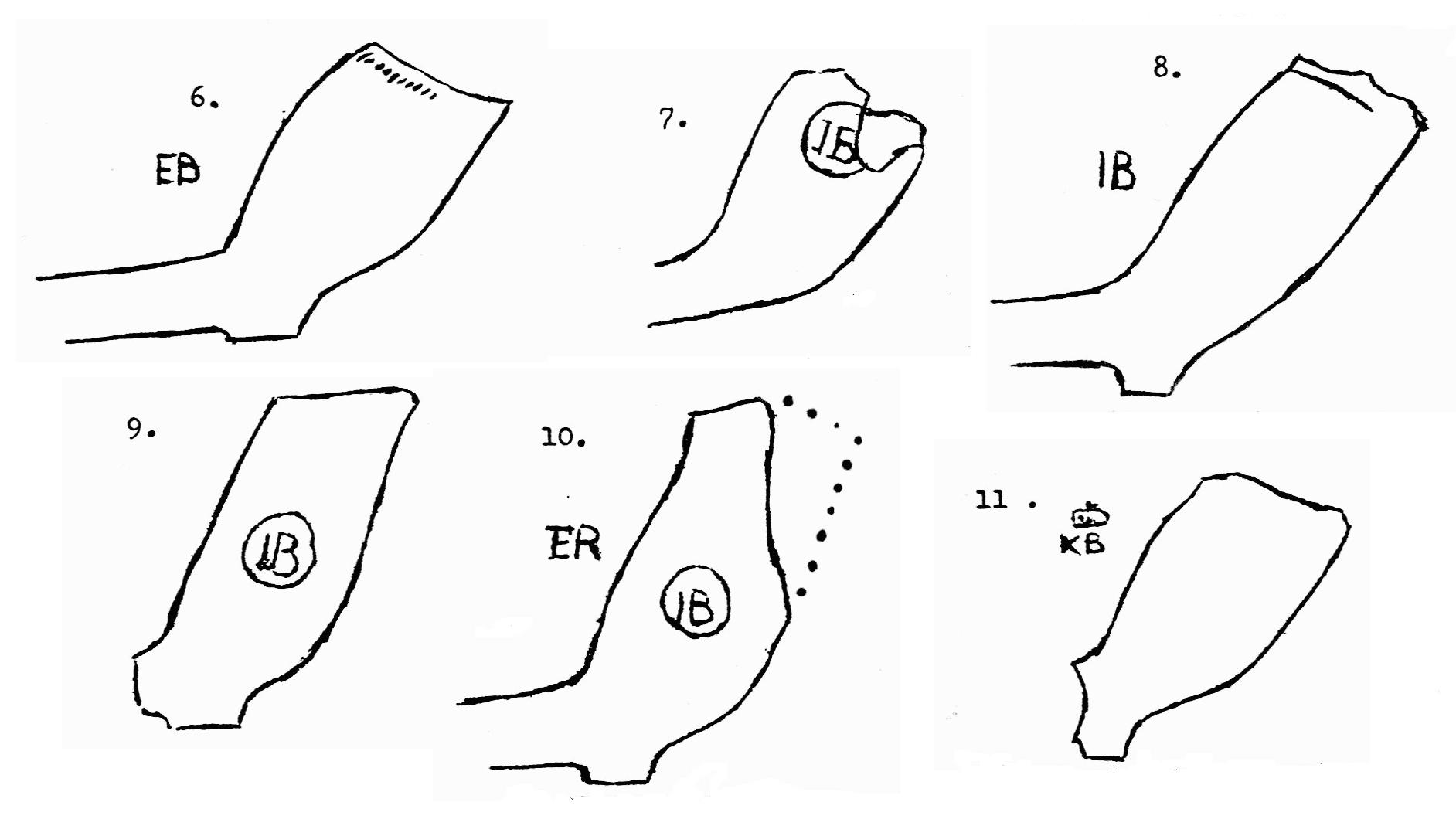

6. EB embossed on base of heel. c.1700. Many different possibilities.

7. IB embossed on right hand side of bowl. c.1690. Many different possible Bristol makers. This shape of pipe very common in America.

8. IB incised on center of bowl. c. 1680-1710. Many different possible Bristol makers.

9. IB embossed on right hand side of bowl. c.1690-1740. Many different possible Bristol makers.

10. IB embossed on right hand side of bowl. Er incised on center of bowl. c.1700-1740. Many different possible Bristol makers.

11. KB embossed on base of heel. c.1680-1720. Maker unknown. Probably Dutch.

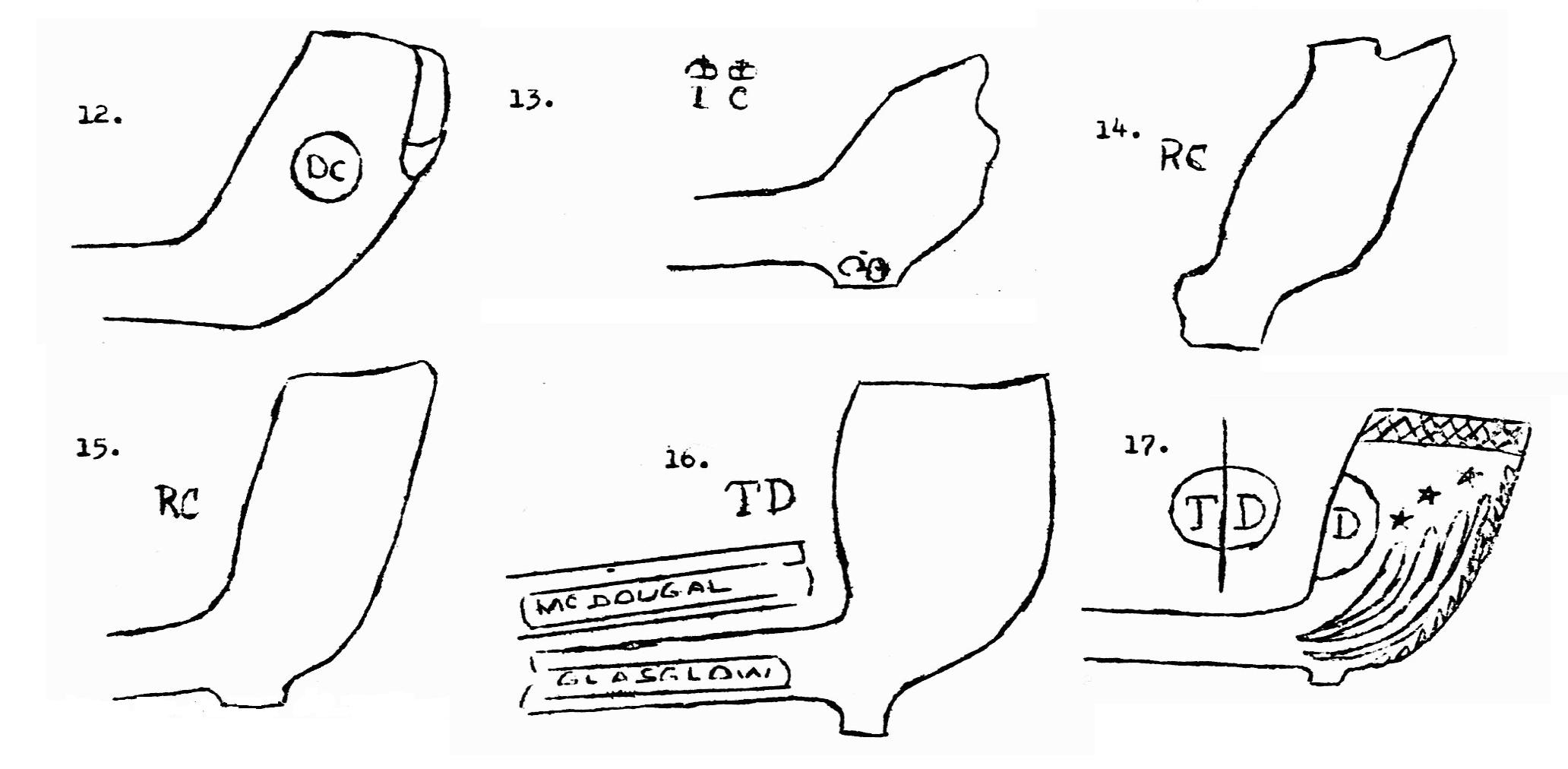

12. DC embossed on right hand side of bowl. c.1700-1730. Daniel Chilton, Bristol, Bolls 1722.

13. I.C. embossed on right and left hand side of heel. c. 1700? Possibly James Chapman, London, Freedom 1682.

14. RC incised on center of bowl. c. 1680-1740. Several different possible Bristol makers.

15. RC incised on center of bowl. c. 1700-1740. Several different possible Bristol makers.

16. TD incised on center of bowl. C. late 19th – early 20th century. McDougalls of Glasglow making TD pipes in 1900. (see Walker, TD pipes, Bulletin of Archaeological Society of Virginia, Vol. 20 No.4)

17. TD embossed in center of bowl. c.Post 1820. (see #16)

18. TD embossed on center of bowl. c.? Possibly Thomas Dennis, Bristol, Freeman 1734

19. TD incised on center of bowl. c.? Possible Thomas Dennis, Bristol, Freeman 1734

20. TD embossed on center of bowl. c. Post 1820. See #16 note.

21. 3ID Mark incised on center of bowl. c.1730-1760. See #16 note.

22. Mark embossed on center of bowl. c.Perhaps 19th century.

23. IE incised on base of heel. c.1690-1730. Either Issac Evans, Bristol, Freeman 1699; or James Edward, Bristol, Freeman 1722

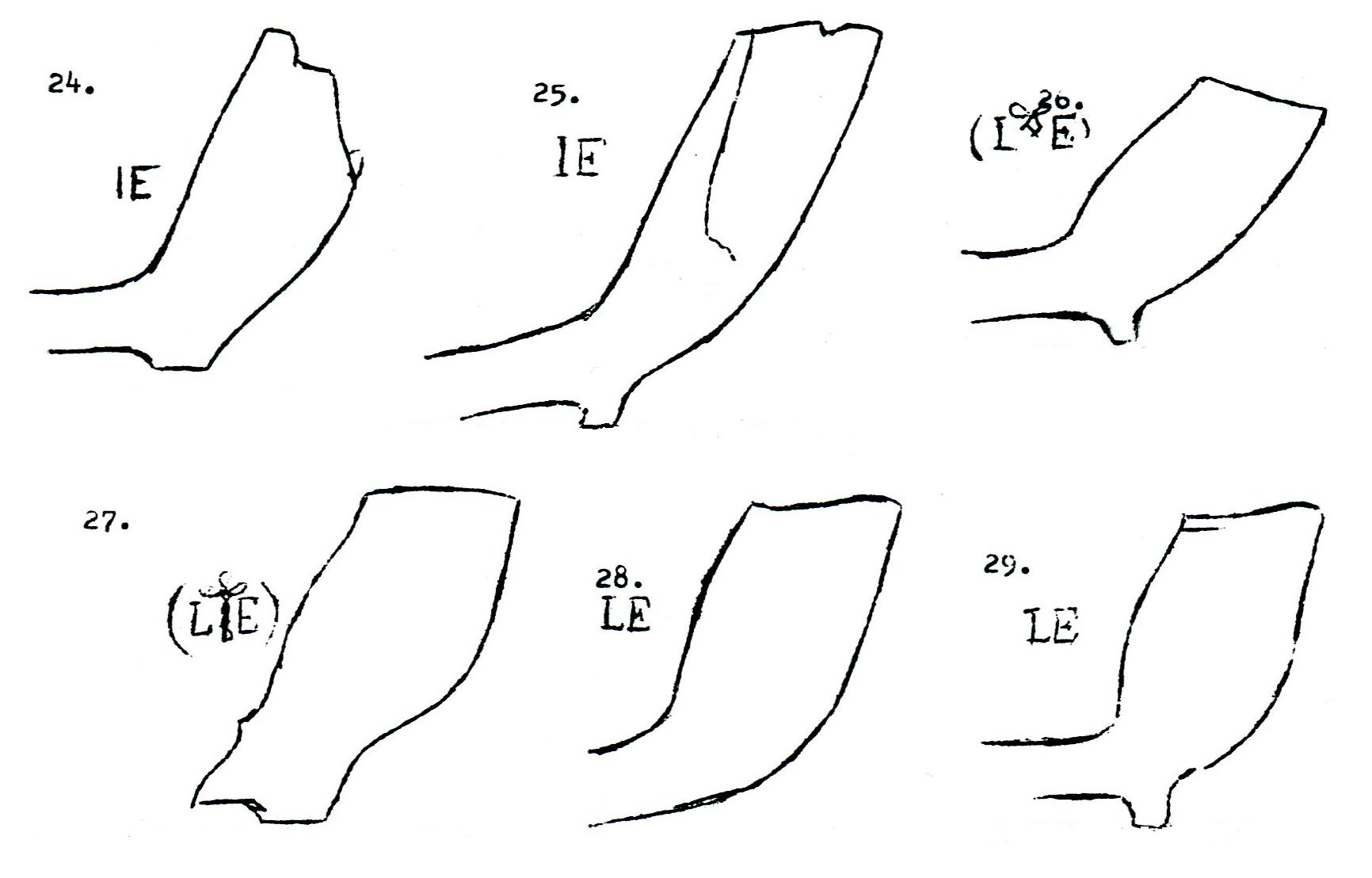

24. IE incised on center of bowl. c. 1690-1740. Probably Issac Evans, Bristol, Freeman 1699

25. IE incised on center of bowl. c. 1680-1710. Probably Issac Evans, Bristol, Freeman 1699

26. LE incised on center of bowl. Pipe made in Hull, probably by William Best who was apprentice to Francis Wood in 1691.

27. LE incised on center of bowl. c. 1690-1700. Lluellin Evans, Bristol, Freeman 1661. He was still known to be making pipes in 1689

28. LE incised on center of bowl. c. 1660-1690. Lluellin Evans, Bristol, Freeman 1661

29. LE incised on center of bowl. c. 1680-1730. Lluellin Evans, Bristol, Freeman 1661.

30. LE incised on center of bowl. c. 1700-1740. Lluellin Evans, Bristol, Freeman 1661.

31. Mark incised on center of bowl. c. 1680-1720. Lluellin Evans, Bristol, Freeman 1661.

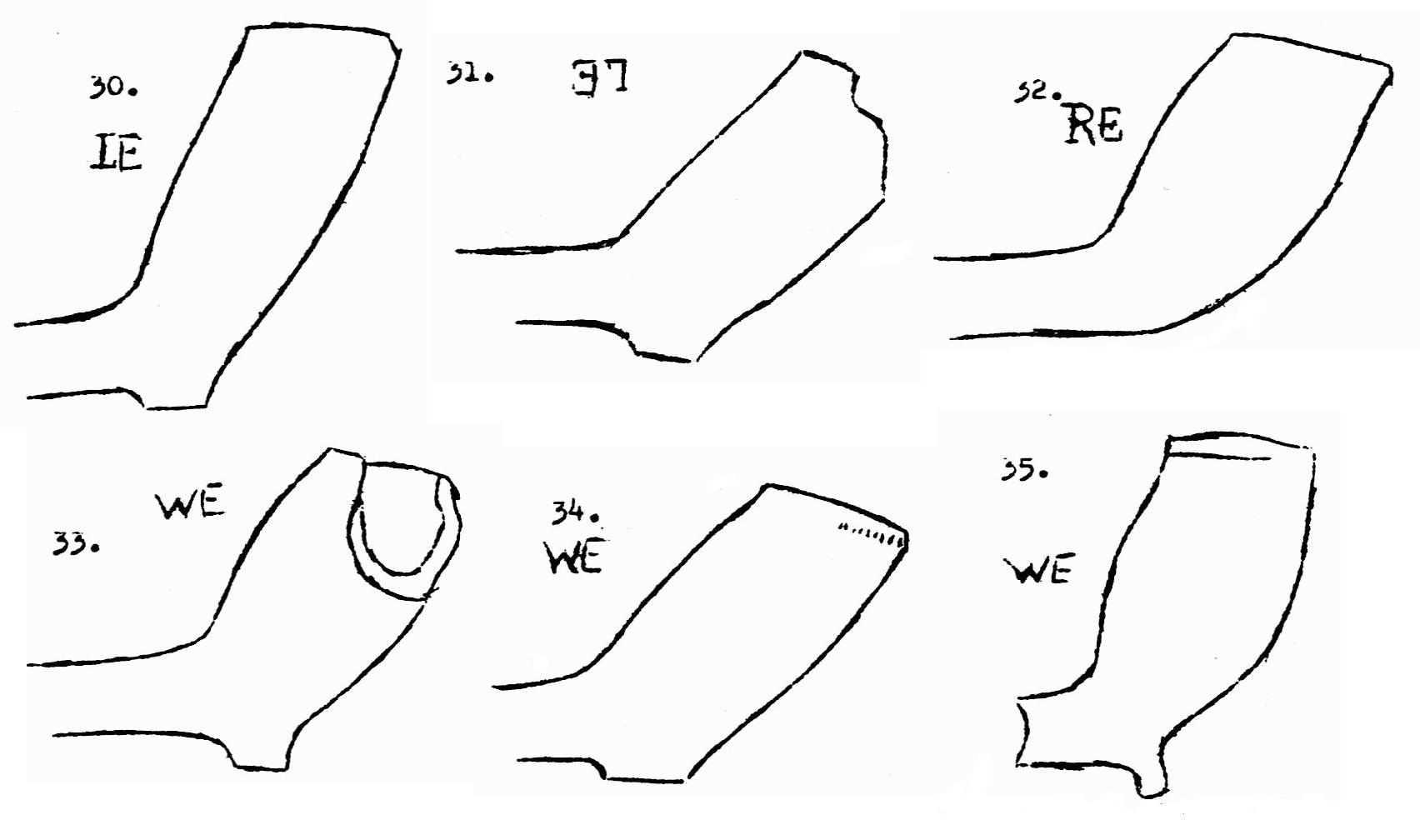

32. RE incised on center of bowl. c. 1700-1730. Edward Randall II, Bristol, Freeman 1661

33. WE incised on center of bowl. c. 1680-1730. Either Walter Evans, Bristol, apprenticed 1661; or William Evans, Bristol, Freeman 1660

34. WE incised on center of bowl. c. 1670-1690. William Evans, Bristol, Freeman 1661

35. WE incised on center of bowl. c. 1680-1730. Either Walter Evans, Bristol, apprenticed 1660; or William Evans, Bristol, Freeman 1660

36.

37.