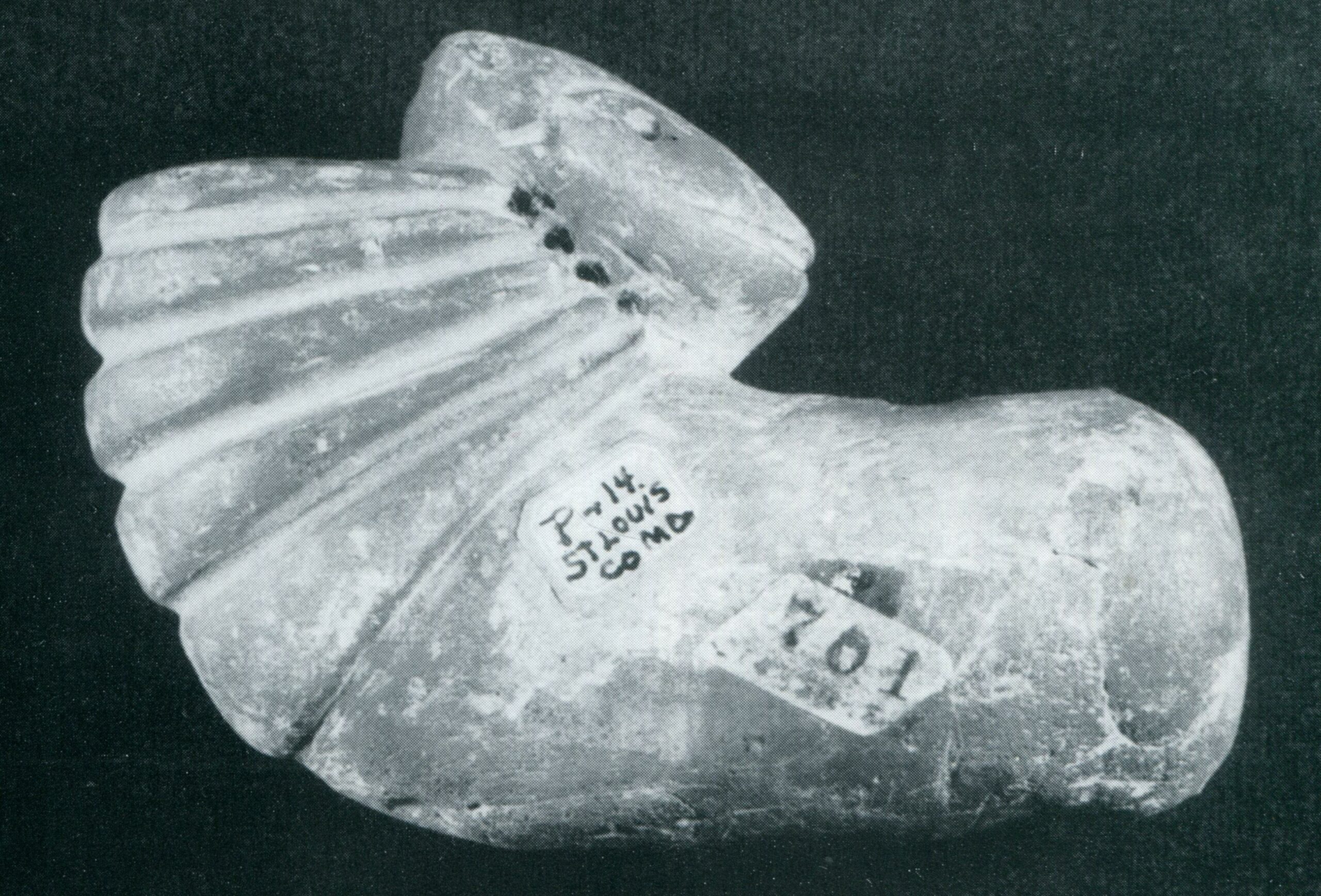

Like all farmers, the Native American knew the woes of pests and the havoc that can be raised by them as they eat away at crops. The effects of the tobacco worm was no less destructive as this pipe suggests.

“Calumet” is a Norman word that was first recorded in David Ferrand’s la Muse normande around 1625–1655. Its first meaning was “sort of reeds used to make pipes”, with a suffix substitution for calumel. It corresponds to the French word chalumeau ‘reeds’, which, in modern French also means ‘straw’ or ‘blowlamp’. Later the word was used by Norman-French settlers in Canada to describe the ceremonial pipes they saw in use among the First Nations people of the region.

“There is in the country an herb which they call tabaco, which is a kind of plant, the stalk of which is as tall as the chest of a man….and they sow this herb and they keep the seed which it produces to sow the next year and they cure it carefully for the purpose of securing predictions.” From The first to mention ‘tobaco’: Oviedo y Valdés on Venezuela

Calumets and other Native American ceremonial pipes have often been given the misnomer “peace pipe”; this is a European construct based on only one type of pipe and one way it was used. Various types of ceremonial pipes have been used by multiple Native American cultures, with the style of pipe, materials smoked, and ceremonies being unique to the distinct religions of those nations. John Walthall notes that pipes are rarely recovered from camp sites, but are almost always carefully placed in burials, indicating their significance in ceremonial life. There were Calumets for everything from war and peace to commerce and trade to social and political decision-making. During his travels down the Mississippi River in 1673 Father Jacques Marquette documented the universal respect that the ceremonial “peace pipe” was shown across all native peoples he encountered, even those at war with each other. He claimed that presenting the pipe during battle would actually halt the fighting. It was for this reason that the Illinois people gave Marquette such a pipe as a gift to assure his safe travel through the interior of the land.

There is little evidence that pre-Columbian Native Americans suffered from addiction to smoking tobacco. Only the medicine-men were daily users of tobacco for healing rituals and for communicating with Spirit. Pipe-keepers were required to be of the highest character and moral standards. Tobacco was smoked during official functions such as tribal councils, and when guests visited the lodge. When hunting parties from neighboring tribes met each other in the field, the pipe was smoked among them to demonstrate peaceful intentions. A warrior seeking vision would pack his bowl with a special smoking mixture supplied by the medicine elder and then carry his pipe into the wilderness to pray for up to four days. During this time he would not drink or eat or smoke but concentrate his full attention on ‘crying-for-a-vision’. Only upon returning to the sweat lodge and relating his experiences to the medicine elder was the pipe smoked in contemplation.

In ceremonial usage, the smoke is believed to carry prayers to the attention of the Creator or other powerful spirits. Lakota tradition has it that White Buffalo Calf Woman, brought the Chanunpa to the people, and instructed them in its symbolism and ceremonies. Most Indian peoples also felt that smoking together helped to create a spirit of congeniality and cooperation. “See our smoke has now filled the room,” said a Delaware Indian from Oklahoma named Jesse Moses to the anthropologist Frank Speck. “First it was in streaks and your smoke and my smoke moved about that way, but now it is all mixed up into one. That is like our minds and spirit too, when we must talk. We are now ready, for we will understand one another better.” The Cherokee consider these offerings to be contracts with the helper spirits that carry our prayers to Creator. Gifting tobacco is a way of showing respect and giving thanks. Above all, tobacco is medicine. It is used in healing ceremonies, teas, poultices, and to pray for good health.

According to oral traditions, and amply illustrated by pre-contact pipes in museums and tribal and private holdings, some ceremonial pipes are adorned with feathers, fur, human or animal hair, beadwork, quills, carvings or other items having significance for the owner. Other pipes are very simple. Many are not kept by an individual, but are instead held collectively by a medicine society or similar ceremonial organization.

The tobacco, or Nicotiana rustica (French), used in Native American pipes was used sparingly and was often mixed with other organic material such as herbs, barks, and plant matter, most often called Kinnikinnick, a Delaware word for the organic mixture. The most popular mixture of this type included tobacco, sumac leaves and dogwood bark. The making of Tobacco is a most sacred aspect of tobacco ceremony. Tobacco leaves are selected, ordered with moisture and cut and blended with herbs to make fragrant smoking mixtures. Each pipe carrier’s mixture is uniquely based on their family’s traditions.

Some northern Sioux people used long, stemmed pipes for ceremonies while others such as the Catawba in the southeast used ceremonial pipes formed as round, footed bowls with a tubular smoke tip projecting from each cardinal direction on the bowl. This is a very rare form of pipe with very few examples in existence.

Some northern Sioux people used long, stemmed pipes for ceremonies while others such as the Catawba in the southeast used ceremonial pipes formed as round, footed bowls with a tubular smoke tip projecting from each cardinal direction on the bowl. This is a very rare form of pipe with very few examples in existence.

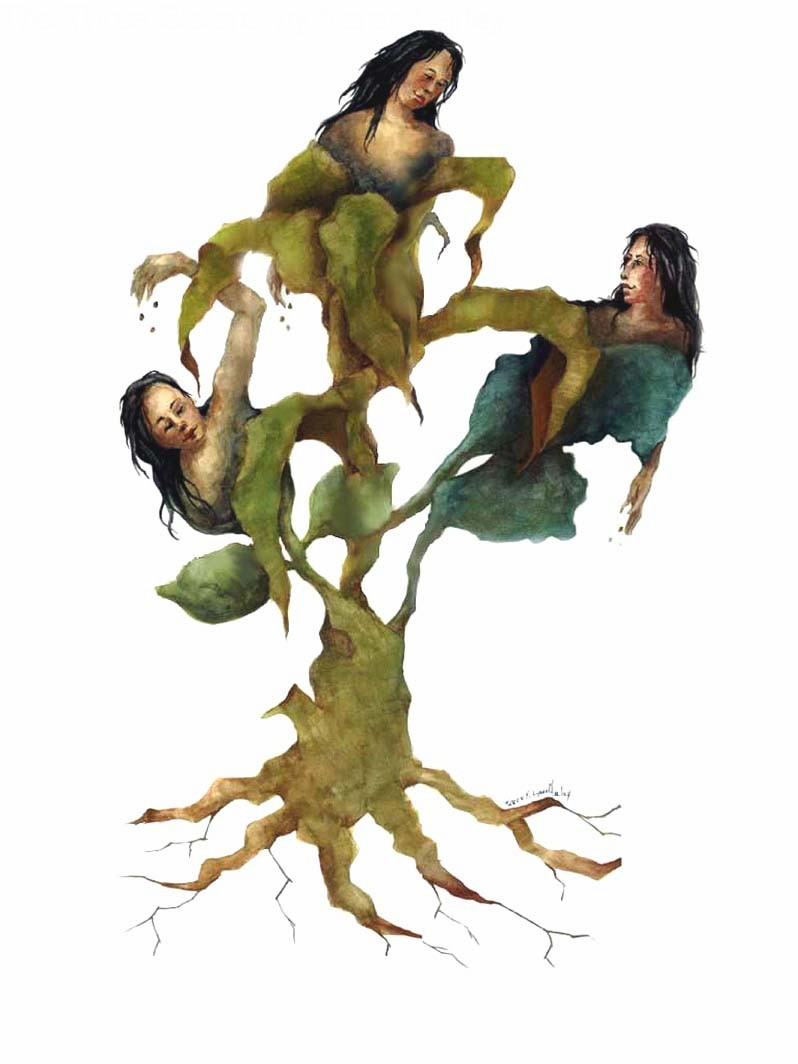

Observing that corn beans and squash grow well together by fertilizing and protecting each other, these diet staples became the ‘Three Sisters’ our Sustainers(pictured right). Buffalo Calf Woman changed herself from a buffalo into a woman and brought the Sacred Pipe Ceremony to the Lakota People. This First Pipe is still kept and revered by the People on Pine Ridge Reservation SD. Through these stories, Native Americans developed a personal relationship with the natural world and better understood its benefits and dangers.

Huron Indian myth has it that in ancient times, when the land was barren and the people were starving, the Great Spirit sent forth a woman to save humanity. As she traveled over the world, everywhere her right hand touched the soil, there grew potatoes. And everywhere her left hand touched the soil, there grew corn. And when the world was rich and fertile, she sat down and rested. When she arose, there grew tobacco.

In 2010, tobacco was found that dates to the Pleistocene Era. Paleontologists from the Meyer-Honninger Paleontology Museum discovered the small block of fossilized tobacco in the Maranon river basin in northeastern Peru. As far as human use of tobacco is concerned, although small amounts of nicotine may be found in some Old World plants, including belladonna and Nicotiana africana, nicotine metabolites have been found in human remains and pipes in the Near East and Africa, but there is no indication of habitual tobacco use in the Ancient world, on any continent before the colonial Americas.

The history of tobacco or “Uppa-woc”, Native America’s most sacred plant begins with its cultivation along with squash and beans around 5000 BC. By 200 BC the Hopewell Mound culture demonstrated a sophisticated ceremonial culture based on the discovery of more than two hundred stone effigy tobacco pipes at the Ohio mound site. Native only to the Americas, tobacco was introduced to European explorers and settlers by the American Indian tribesman who greeted them. Their first gifts to Columbus and later to the settlers at Jamestown included tobacco.

Between 470 and 630 A.D. the Mayas began to scatter, some moving as far as the Mississippi Valley. Two castes of smokers emerged among them. Those in the Court of Montezuma, who mingled tobacco with the resin of other leaves and smoked pipes with great ceremony after their evening meal; and the lesser Indians, who rolled tobacco leaves together to form a crude cigar.

Many pre-Columbian tribes-people were adept agriculturalists. They grew food crops to supplant their diet of wild plants and game and to sustain their People during lean times. Without draft animals or iron plows, Native American farming was very labor intensive. The devotion of limited human resources to growing a crop such as tobacco that has no food or fiber value indicates that it was very precious. Among the Yanomamo of Brazil, the word for being poor, (hori), means literally “without tobacco.”

Like all farmers, the Native American knew the woes of pests and the havoc that can be raised by them as they eat away at crops. The effects of the tobacco worm was no less destructive as this pipe suggests.