The Cherokee are a Native American people historically settled in the Southeastern United States (principally Georgia, the Carolinas and East Tennessee. Linguistically, they are part of the Iroquoian language family. In the 19th century, historians recorded their oral tradition that told of the tribe having migrated south in ancient times from the Great Lakes region, where other Iroquoian-speaking peoples were located. They began to have contact with European traders in the 18th century.

Origin

In the 19th century, white settlers in the United States called the Cherokee one of the “Five Civilized Tribes”, because they had assimilated numerous cultural and technological practices of European American settlers. The Cherokee refer to themselves as Tsalagi or Aniyvwiyai, which means “Principal People.” The Iroquois, who were based in New York, called the Cherokee Oyata’ge’ronoñ (inhabitants of the cave country).

There are two prevailing views about Cherokee origins. One is that the Cherokee, an Iroquoian-speaking people, are relative latecomers to Southern Appalachia, who may have migrated in late prehistoric times from northern areas, the traditional territory of the later Haudenosaunee five nations and other Iroquoian-speaking peoples. Researchers in the 19th century recorded conversations with elders who recounted an oral tradition of the Cherokee people’s migrating south from the Great Lakes region in ancient times. The other theory, which is disputed by academic specialists, is that the Cherokee had been in the Southeast for thousands of years. There is no archeological evidence for this.

Early Culture

Some traditionalists, historians and archaeologists believe that the Cherokee did not come to Appalachia until the 15th century or later. They may have migrated from the north and moved south into Muscogee Creek territory and settled at the sites of mounds built by the Mississippian culture. During early research, archeologists had mistakenly attributed several Mississippian culture sites to the Cherokee, including Moundville and Etowah Mounds. Late 20th-century studies have shown conclusively instead that the weight of archaeological evidence at the sites shows they are unquestionably related to ancestors of Muskogean peoples rather than to the Cherokee.

Pre-contact Cherokee are considered to be part of the later Pisgah Phase of Southern Appalachia, which lasted from circa 1000 to 1500. Despite the consensus among most specialists in Southeast archeology and anthropology, some scholars contend that ancestors of the Cherokee people lived in western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee for a far longer period of time. During the Late Archaic and Woodland periods, Indians in the region began to cultivate plants such as marsh elder, lambsquarters, pigweed, sunflowers and some native squash. People created new art forms such as shell gorgets, adopted new technologies, and followed an elaborate cycle of religious ceremonies. During the Mississippian Culture-period (800 to 1500 CE), local women developed a new variety of maize (corn) called eastern flint. It closely resembled modern corn and produced larger crops. The successful cultivation of corn surpluses allowed the rise of larger, more complex chiefdoms with several villages and concentrated populations during this period. Corn became celebrated among numerous peoples in religious ceremonies, especially the Green Corn Ceremony.

Much of what is known about pre-18th-century Native American cultures has come from records of Spanish expeditions. The earliest records, dating to the mid-16th century, tell of encounters with people of the Mississippian culture. These people were the ancestors to later tribes in the Southeast such as the Creek and Catawba. The Cherokee arrived later, descended from a different people, but they occupied some of the ancient Mississippian sites and were observed by the Spanish.

The American writer John Howard Payne wrote about pre-19th century Cherokee culture and society. The Payne papers describe the account by Cherokee elders of a traditional two-part societal structure. A “white” organization of elders represented the seven clans. As Payne recounted, this group, which was hereditary and priestly, was responsible for religious activities, such as healing, purification, and prayer. A second group of younger men, the “red” organization, was responsible for warfare. The Cherokee considered warfare a polluting activity, and warriors required the purification by the priestly class before participants could reintegrate into normal village life. This hierarchy had disappeared long before the 18th century.

Another major source of early cultural history comes from materials written in the 19th century by the Cherokee medicine men, after Sequoyah’s creation of the Cherokee syllabary in the 1820s. Initially only the medicine men adopted and used such materials, which were considered extremely powerful in a spiritual sense. Later, the syllabary and writings were widely adopted by the Cherokee people.

Unlike most other Indians in the American Southeast at the start of the historic era, the Cherokee spoke an Iroquoian language. Since the Great Lakes region was the core of Iroquoian-language speakers, scholars have theorized that the Cherokee migrated South from that region. This is supported by the Cherokee oral history tradition. According to the scholars’ theory, the Tuscaroa, another Iroquoian-speaking people who inhabited the Southeast in historic times, and the Cherokee broke off from the major group during its northern migration.

Other historians hold that, judging from linguistic and cultural data, the Tuscarora people migrated South from other Iroquoian-speaking people in the Great Lakes region in ancient times. In the 1700s, the Tuscarora left the Southeast and “returned” to the New York area by 1722 because of warfare in the southern region. The Tuscarora were admitted by the Iroquois as the Sixth Nation of their political confederacy.

Linguistic analysis shows a relatively large difference between Cherokee and the northern Iroquoian languages. Scholars posit a split between the groups in the distant past, perhaps 3500–3800 years ago. Glottochronology studies suggest the split occurred between about 1,500 and 1,800 BCE. The Cherokee have claimed the ancient settlement of Kituwa on the Tuckasegee River, formerly next to and now part of Qualla Boundary (the reservation of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians), as the original Cherokee settlement in the Southeast.

History

17th century: English contact

Virginian traders developed a small-scale trading system with the Cherokee before the end of the 17th century; the earliest recorded Virginia trader to visit the Cherokee was a certain Dority, in 1690. The Cherokee sold the traders Indian slaves for use as laborers in Virginia and further north.

An indication of early trade with European settlers, especially to the north, are very early powder horns made from woodland bison. These bison were hunted to extinction by 1700. The horns of the woodland bison were brown in contrast to the black horns of the western bison and were favored for powder horns among the Indians. Native Americans often placed brass tacks within a circle of tacks on the horn’s plug to illustrate the shape of a constellation visible at the time of a special event such as the birth of a child. The French traders were among the earliest settlers to arm the Indians with guns, both for hunting and as allies against the English.

18th century

The Cherokees gave sanctuary to a band of Shawnee in the 1660s, but from 1710 to 1715 the Cherokee and Chickasaw, allied with the British, fought Shawnee, who were allied with the French, and forced them to move northward.

Cherokees fought with the Yamasee, Catawaba, and British in late 1712 and early 1713 against the Tuscarora in the Second Tuscarora War. The Tuscarora War marked the beginning of an English-Cherokee relationship that, despite breaking down on occasion, remained strong for much of the 18th century. With the growth of the deerskin trade, the Cherokee were valuable trading partners, since deer-skins from the cooler country of their mountain hunting-grounds were of a better-quality than those supplied by neighboring tribes.

The Barnett trade gun was among the early trade guns supplied to the Indians. These guns armed the Westo and Creek tribes, making them valuable trade partners, but also making them stronger than their unarmed neighboring Yamasee and Guale neighbors, allowing them to raid, capture, and enslave the unarmed tribes that were reliant on a Spanish mission system that refused to arm them.

In January 1716, Cherokee murdered a delegation of Muscogee Creek leaders at the town of Tugaloo, marking their entry into the Yamasee War. It ended in 1717 with peace treaties between South Carolina and the Creek. Hostility and sporadic raids between the Cherokee and Creek continued for decades.

These raids came to a head at the Battle of Taliwa in 1755, present-day Ball Ground, Georgia, with the defeat of the Muscukee.

Stickball was a popular game among the Cherokee people. The ball had a stone core that was covered with sewn hide.

Some records indicate Ball Ground was originally named Battle Ground on early maps. Two and one-half miles to the east of the town, near the confluence of Long-Swamp Creek and the Etowah River, is the traditional site of the Battle of Taliwa, the most decisive battle of the war between Cherokee and Creek Indians in the 18th century. Cherokee history tells that the conflict over territory was determined by a stickball game here.

In 1721, the Cherokee ceded lands in South Carolina. In 1730, at Nikwasi, a former Mississippian culture site, a Scots adventurer, Sir Alexander Cumming, crowned Moytoy of Tellico as “Emperor” of the Cherokee. Moytoy agreed to recognize King George II of Great Britain as the Cherokee protector. Cumming arranged to take seven prominent Cherokee, including Attakullakulla, to London, England. The Cherokee delegation signed the Treaty of Whitehall with the British. Moytoy’s son, Amo-sgasite(Dreadful Water) attempted to succeed him as “Emperor” in 1741, but the Cherokees elected their own leader, Cunne Shote (Standing Turkey) of Chota.

Political power among the Cherokee remained decentralized and towns acted autonomously. In 1735 the Cherokee were estimated to have sixty-four towns and villages, and 6,000 fighting men.

In 1738 and 1739 smallpox epidemics broke out among the Cherokee, who had no natural immunity. Nearly half their population died within a year. Hundreds of other Cherokee committed suicide due to their losses and disfigurement from the disease.

From 1753 to 1755, battles broke out between the Cherokee and Muscogee over disputed hunting grounds in northern Georgia. The Cherokee were victorious in the Battle of Taliwa.

British soldiers built forts in Cherokee country to defend against the French in the Seven Years War, called the French and Indian War in North America. These included Fort Loudoun near Chota.

In 1756 the Cherokee were allies of the British in the French and Indian War. Serious misunderstandings arose quickly between the two allies, resulting in the 1760 Anglo-Cherokee War.

King George III’s Royal Proclamation of 1763 forbade British settlements west of the Appalachian crest, as his government tried to afford some protection from colonial encroachment to the Cherokee and other tribes. The ruling was difficult to enforce.

In 1771–1772, North Carolinian settlers squatted on Cherokee lands in Tennessee, forming the Watauga Association. Daniel Boone and his party tried to settle in Kentucky, but the Shawnee, Delaware, Mingo, and some Cherokee attacked a scouting and forage party that included Boone’s son. The American Indians used this territory as a hunting ground; it had hardly been inhabited for years. The conflict sparked the beginning of what was known as Dunmore’s War (1773–1774).

In 1776, allied with the Shawnee led by Cornstalk, Cherokee attacked settlers in South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, and North Carolina in the Second Cherokee War. Overhill Cherokee Nancy Ward, Dragging Canoe’s cousin, warned settlers of impending attacks. Provincial militias retaliated, destroying over 50 Cherokee towns. North Carolina militia in 1776 and 1780 invaded and destroyed the Overhill towns. In 1777 surviving Cherokee town leaders signed treaties with the states.

Dragging Canoe and his band moved near present-day Chattanooga, Tennessee, where they established 11 new towns. Chickamauga was his headquarters and his entire band became known as the Chickamauga. From here he fought a guerrilla war against settlers, the Chikamauga Wars (1776-1794). The first Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse, signed November 7, 1794, ended the Chickamauga Wars. In 1805, the Cherokee ceded their lands between the Cumberland and Duck rivers (i.e. the Cumberland Plateau) to Tennessee.

19th century

The Cherokee lands between the Tennessee and Chattahoochee rivers were remote enough from white settlers to remain independent after the Chickamauga Wars.

The deerskin trade was no longer feasible on their greatly reduced lands, and over the next several decades, the people of the fledgling Cherokee Nation began to build a new society modeled on the white Southern United States.

George Washington sought to ‘civilize’ Southeastern American Indians, through programs overseen by the Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins. He encouraged the Cherokee to abandon their communal land-tenure and settle on individual farmsteads, facilitated by the destruction of many American Indian towns during the American Revolutionary War.

The deerskin trade brought white-tailed deer to the brink of extinction, and as pigs and cattle were introduced, they became the principal sources of meat. The government supplied the tribes with spinning wheels and cotton-seed, and men were taught to fence and plow the land, in contrast to their traditional division in which crop cultivation was woman’s labor. Americans instructed the women in weaving. Eventually Hawkins helped them set up blacksmiths, gristmills and cotton plantations.

Boyd Check Stamped pottery is found in northwestern Georgia. The Cherokee were very late moving into norwestern Georgia. It was after 1770, during the American Revolution when their homeland was broken up, particularly northwestern South Carolina and northeastern Georgia. There is similar material found in northeastern Georgia that occurred before the 18th century, but most people have not called this pottery Boyd Check Stamped.

The Cherokee organized a national government under Principal Chiefs Little Turkey (1788–1801), Black Fox (1801–1811), and Pathkiller (1811–1827), all former warriors of Dragging Canoe. The ‘Cherokee triumvirate’ of James Vann and his protégés The Ridge and Charles R. Hicks advocated acculturation, formal education, and modern methods of farming.

Galt Check Stamped and Galt Simple Stamped are both Cherokee pottery types that date to the 18th and 19th centuries.

In 1801 they invited Moravian missionaries from North Carolina to teach Christianity and the ‘arts of civilized life.’ The Moravians and later Congregationalist missionaries ran boarding schools, and a select few students were educated at the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions school in Connecticut.

In 1806 a Federal Road from Savannah, Georgia to Knoxville, Tennessee was built through Cherokee land. Chief James Vann opened a tavern, inn and ferry across the Chattahoochee and built a cotton-plantation on a spur of the road from Athens, Georgia to Nashville. His son ‘Rich Joe’ Vann developed the plantation to 800 acres (3.2 km2), cultivated by 150 slaves. He exported cotton to England, and owned a steamboat on the Tennessee River.

The battle against the Red Stick Creek that lived in Alabama took place at a place called Horsehoe Bend. The area is not a military park.

The Cherokee allied with the U.S. against the nativist and pro-British Red Stick faction of the Upper Creek in the Creek War during the War of 1812, and Cherokee warriors led by Major Ridge played a major role in General Andrew Jackson’s victory at the Battle of Horshoe Bend.

Major Ridge moved his family to Rome, Georgia, where he built a substantial house, developed a large plantation and ran a ferry on the Oostanaula River. Although he never learned English, he educated his son and nephews in New England mission schools.

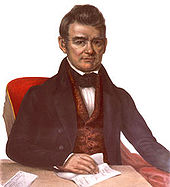

His interpreter and protégé Chief John Ross, the descendant of several generations of Cherokee women and Scots fur-traders, built a plantation and operated a trading firm and a ferry at Ross’ Landing (Chattanooga Tennessee). During this period, divisions arose between the acculturated elite and the great majority of Cherokee, who clung to traditional ways of life.

Built before the start of the 19th century by John McDonald, a Scottish trader of wandering loyalty, the Ross House is the oldest remaining structure in Northwest Georgia. McDonald was one of a group of Scot traders that mingled easily with the Cherokee. At various times he claimed loyalty to France, Spain, England and the United States.

He moved to Cherokee country from Charleston, South Carolina by way of Fort Loudon, near Knoxville, where he met his wife, a mixed blood Cherokee named Anne Shorey. They had one daughter, Mollie. McDonald saved a young man, Daniel Ross, from certain death at the hands of Bloody Fellow, a Chickamauga Cherokee. Within a year Ross married Mollie and moved to Turkeytown where John Ross was born.

McDonald began to build a home on the Cherokee Trading Path near Poplar Spring, probably in 1797. When Mollie Ross died in 1808, her 18 year-old son John Ross moved to the home with his grandfather John McDonald. Ross had received much of his formal education in the home, along with the sons of other Cherokee and countrymen, whites who had been accepted into the Cherokee Nation.

The home served as post office, country store, schoolhouse, and council room during the period that Ross lived in it. Starting in the early 1820’s Ross began to spend more time at Head of Coosa, the Cherokee town at the confluence of the Etowah and Oostanaula Rivers, where Ross owned a ferry and additional property (now Rome, Georgia). In 1827 he sold the home to a relative.

At what point the home became known as the Ross House is unclear, but it probably was shortly after John’s arrival in 1808. Poplar Springs became known as Rossville by 1813 and young John founded the town of Ross’s Landing about that time. Today Ross’s Landing is known as Chattanooga, Tennessee. The Tennessee Aquarium is located near the site of the original landing.

During the battle of Chickamauga the home was headquarters for Gordon Grainger. Designated as reserves, Grainger and his men held a position near the house for most of the day, observing the battle. When he saw Major General George Thomas holding a thin line around Snodgrass Hill, Grainger, on his own initiative, ordered General Steedman’s division to advance, resupplying the desperate Union Army.

Learn more about it:

John Ross

Index of Cherokee-related pages on About North Georgia

Around 1809 Sequoyah began developing a written form of the Cherokee language. He spoke no English, but his experiences, as a silversmith dealing regularly with white settlers and as a warrior at Horseshoe Bend, convinced him the Cherokee needed to develop writing.

In 1821, he introduced Cherokee syllabary, the first written syllabic form of an American Indian language outside of Central America. Initially his innovation was opposed by both Cherokee traditionalists and white missionaries who sought to encourage the use of English. When Sequoyah taught children to read and write with the syllabary, he reached the adults and, by the 1820s, the Cherokee had a higher rate of literacy than the whites around them in Georgia.

In 1819, the Cherokee began holding council meetings at New Town, at the headwaters of the Oostanaula (near present-day Calhoun, Georgia). In November 1825, New Town became the capital of the Cherokee Nation, and was renamed New Echota, after the Overhill Cherokee principal town of Chota. Sequoyah’s syllabary was adopted. They had developed a police force, a judicial system, and a National Committee.

In 1827, the Cherokee Nation drafted a Constitution modeled on the United States, with executive, legislative and judicial branches and a system of checks and balances. The two-tiered legislature was led by Major Ridge and his son John Ridge. Convinced the tribe’s survival required English-speaking leaders who could negotiate with the U.S., the legislature appointed John Ross as Principal Chief. A printing press was established at New Echota by the Vermont missionary Samuel Worcester and Major Ridge’s nephew Elias Boudinot, who had taken the name of his white benefactor, a leader of the Continental Congress and New Jersey Congressman.

They translated the Bible was translated into Cherokee syllabary. Boudinot published the first edition of the bilingual ‘Cherokee Phoenix,’ the first American Indian newspaper, in February 1828.

Removal Era

Before the final removal to present-day Oklahoma, many Cherokees relocated to present-day Arkansas, Missouri and Texas. Between 1775 and 1786 the Cherokee, along with people of other nations such as the Choctaw and Chickasaw, began voluntarily settling along the Arkansas and Red Rivers.

In 1802, the federal government promised to extinguish Indian titles to lands claimed by Georgia in return for Georgia’s cession of the western lands that became Alabama and Mississippi.

To convince the Cherokee to move voluntarily in 1815, the US government established a Cherokee Reservation in Arkansas. The reservation boundaries extended from north of the Arkansas River to the southern bank of the White River. Di’wali (The Bowl), Sequoyah, Spring Frog and Tatsi (Dutch) and their bands settled there. These Cherokees became known as “Old Settlers.”

The Cherokee eventually migrated as far north as the Missouri Bootheel by 1816. They lived interspersed among the Delawares and Shawnees of that area.

The Cherokee in Missouri Territory increased rapidly in population, from 1,000 to 6,000 over the next year (1816–1817), according to reports by Governor William Clark.

Increased conflicts with the Osage Nation led to the Battle of Claremore Mound and the eventual establishment of Fort Smith between Cherokee and Osage communities.

In the Treaty of St. Louis (1825), the Osage were made to “cede and relinquish to the United States, all their right, title, interest, and claim, to lands lying within the State of Missouri and Territory of Arkansas…” to make room for the Cherokee and the Mashcoux, Muscogee Creeks.

As late as the winter of 1838, Cherokee and Creek living in the Missouri and Arkansas areas petitioned the War Department to remove the Osage from the area.

A group of Cherokee traditionalists led by Di’wali moved to Spanish Texas in 1819. Settling near Nacogdches, they were welcomed by Mexican authorities as potential allies against Anglo-American colonists. The Texas Cherokees were mostly neutral during the Texas War of Independence. In 1836, they signed a treaty with Texas President Sam Houston, an adopted member of the Cherokee tribe. His successor Mirabeau Lamar sent militia to evict them in 1839.

Trail of Tears

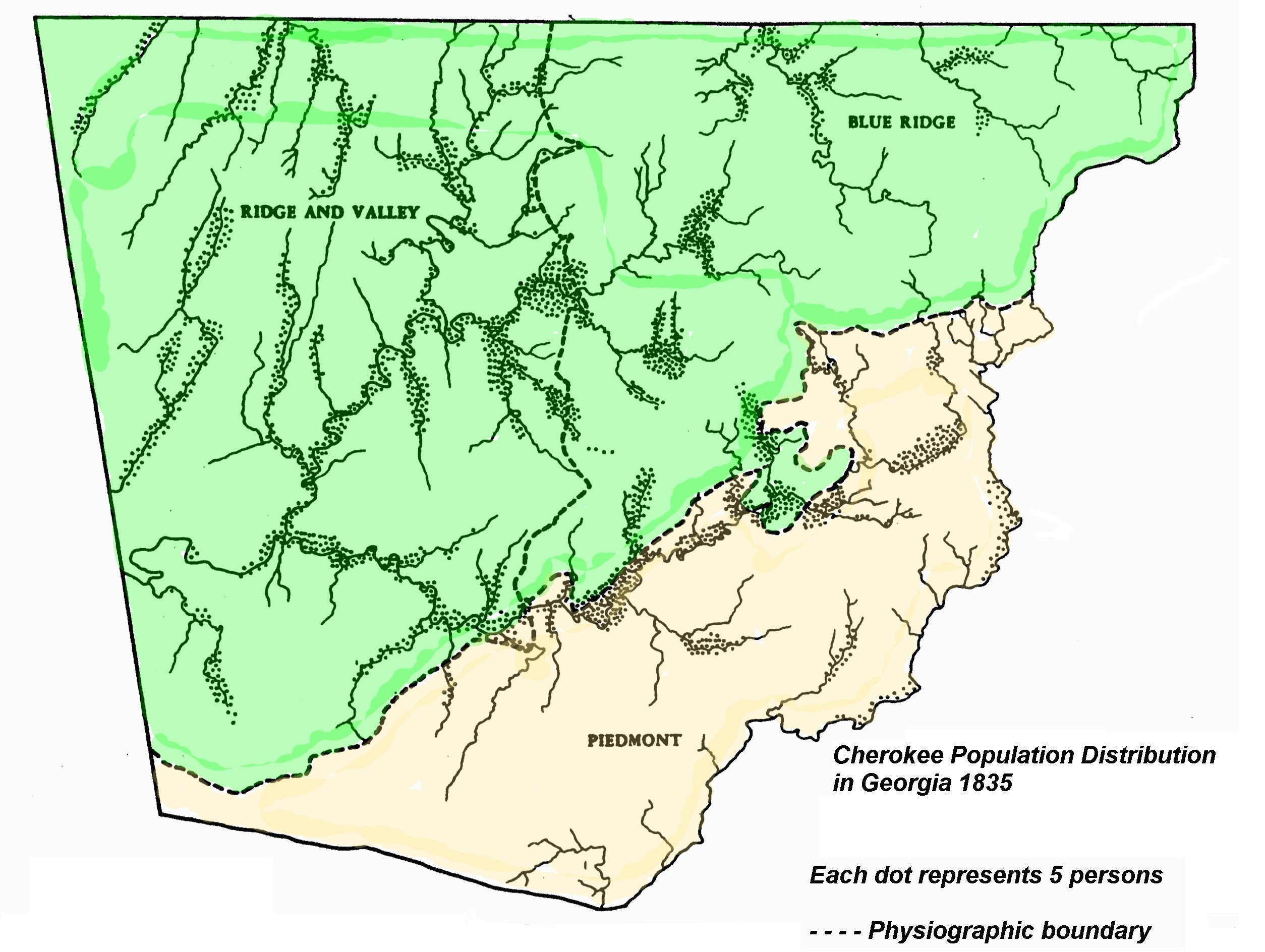

During the first decades of the 19th century, Georgia focused on removing the Cherokee’s neighbors, the Lower Creek. The Georgia Governor George Troup and his cousin William McIntosh, chief of the Lower Creek, signed the Treaty of Indian Springs (1825), ceding the last Muscogee (Creek) lands claimed by Georgia. The state’s northwestern border reached the Chattahoochee, the border of the Cherokee Nation.

In 1829, gold was discovered at Dahlonega, on Cherokee land claimed by Georgia. The Georgia Gold Rosh was the first in U.S. history, and state officials demanded that the federal government expel the Cherokee.

When Andrew Jackson was inaugurated as President in 1829, Georgia gained a strong ally in Washington. In 1830 Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, authorizing the forcible relocation of American Indians east of the Mississippi to a new Indian Territory.

Andrew Jackson said the removal policy was an effort to prevent the Cherokee from facing extinction as a people, which he considered the fate that “the Mohegan, the Narragansett, and the Delaware” had suffered. But, there is ample evidence that the Cherokee were adapting modern farming techniques. A modern analysis shows that the area was in general in a state of economic surplus and could have accommodated both the Cherokee and new settlers.

The Cherokee brought their grievances to a US judicial review that set a precedent in Indian Country. John Ross traveled to Washington, D.C., and won support from National Republican Party leaders Henry Clay and Daniel Webster. Samuel Worcester campaigned on behalf of the Cherokee in New England, where their cause was taken up by Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In June 1830, a delegation led by Chief Ross defended Cherokee rights before the U.S. Supreme Court in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia.

In 1831 Georgia militia arrested Samuel Worcester for residing on Indian lands without a state permit, imprisoning him in Milledgville.

In Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the US Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that American Indian nations were “distinct, independent political communities retaining their original natural rights,” and entitled to federal protection from the actions of state governments that infringed on their soverignty. Worcester v. Georgia is considered one of the most important dicta in law dealing with Native Americans.

Jackson ignored the Supreme Court’s ruling, as he needed to conciliate Southern sectionalism during the era of the Nullification Crisis. His landslide reelection in 1832 emboldened calls for Cherokee removal.

Georgia sold Cherokee lands to its citizens in a Land Lottery, and the state militia occupied New Echota.

The Cherokee National Council, led by John Ross, fled to Red Clay, a remote valley north of Georgia’s land claim. Ross had the support of Cherokee traditionalists, who could not imagine removal from their ancestral lands.

A small group known as the “Ridge Party” or the “Treaty Party” saw relocation as inevitable and believed the Cherokee Nation needed to make the best deal to preserve their rights in Indian Territory. Led by Major Ridge, John Ridge and Elias Boudinot, they represented the Cherokee elite, whose homes, plantations and businesses were confiscated, or under threat of being taken by white squatters with Georgia land-titles. With capital to acquire new lands, they were more inclined to accept relocation.

On December 29, 1835, the “Ridge Party” signed the Treaty of New Echota, stipulating terms and conditions for the removal of the Cherokee Nation. In return for their lands, the Cherokee were promised a large tract in the Indian Territory, $5 million, and $300,000 for improvements on their new lands.

John Ross gathered over 15,000 signatures for a petition to the U.S. Senate, insisting that the treaty was invalid because it did not have the support of the majority of the Cherokee people. The Senate passed the Treaty of New Echota by a one-vote margin. It was enacted into law in May 1836.

Two years later President Martin Van Buren ordered 7,000 Federal troops and state militia under General Winfield Scott into Cherokee lands to evict the tribe. Over 16,000 Cherokee were forcibly relocated westward to Indian Territory in 1838–1839, a migration known as the Trail of Tears or in Cherokee ᏅᎾ ᏓᎤᎳ ᏨᏱ or Nvna Daula Tsvyi (The Trail Where They Cried), although it is described by another word Tlo-va-sa (The Removal). Marched over 800 miles (1,300 km) across Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri and Arkansas, the people suffered from disease, exposure and starvation, and as many as 4,000 died. As some Cherokees were slaveholders, they took enslaved African Americans with them west of the Mississippi. Intermarried European Americans and missionaries also walked the Trail of Tears. Ross preserved a vestige of independence by negotiating for the Cherokee to conduct their own removal under U.S. supervision.

In keeping with the tribe’s “blood law” that prescribed the death penalty for Cherokee who sold lands, Ross’s son arranged the murder of the leaders of the “Treaty Party”. On June 22, 1839, a party of twenty-five Ross supporters assassinated Major Ridge, John Ridge and Elias Boudinot. The party included Daniel Colston, John Vann, Archibald, James and Joseph Spear. Boudinot’s brother Stand Watie fought and survived that day, escaping to Arkansas.

In 1827, Sequoyah had led a delegation of Old Settlers to Washington, D.C. to negotiate for the exchange of Arkansas land for land in Indian Territory. After the Trail of Tears, he helped mediate divisions between the Old Settlers and the rival factions of the more recent arrivals. In 1839, as President of the Western Cherokee, Sequoyah signed an Act of Union with John Ross that reunited the two groups of the Cherokee Nation.