In addition to two groups of Muskhogean people bearing this name1 it should be noticed that it was popularly applied by the whites to a Cherokee town, properly called Ukwû‛nû (or Ukwû‛nĭ),2 but the similarity may be merely a coincidence. Of the two Creek groups mentioned one seems to be associated exclusively with the Florida tribes, while the second, when we first hear of it, was on the Georgia river which still bears its name. The first reference to either appears to be in a report of the Timucua missionary, Fareja, dated 1602. He mentions the “Ocony,” three days’ journey from San Pedro, among a number of tribes among which there were Christians or which desired missionaries.3 In a letter dated April 8, 1608, Ibarra speaks of “the chief of Ocone which marches on the province of Tama.”3 This might apply to either Oconee division. The mission lists of 1655 contain a station called Santiago de Ocone, described as an island and said to be 30 leagues from St. Augustine. As it was certainly not southward of the colonial capital it would seem to have been near the coast to the north, according to the distance given, in the neighborhood of Jekyl Island. At the very same time there was another Oconee mission among the Apalachee called San Francisco de Apalache in the list of 1655; it is given in the list of 1,680 as San Francisco de Oconi.4 This group probably remained with the rest of the Apalachee towns and followed their fortunes.

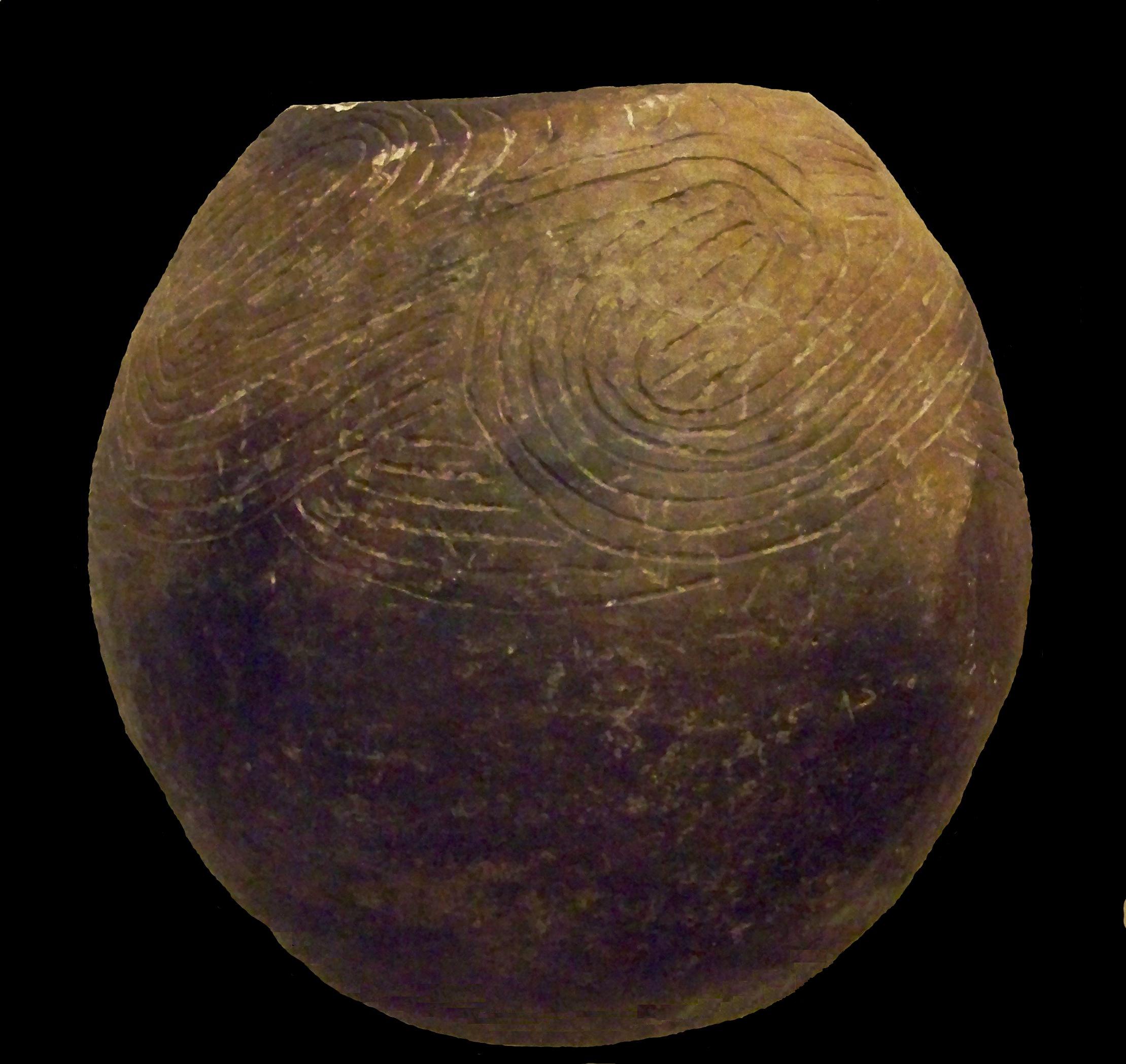

The people of the Oconee River valley made a special kind of incised pottery (Oconee Incised) that was carefully done and some vessels had many different patterns on them.

The main body of the Oconee was located, when first known to Englishmen, on Oconee River, about 4 miles south of the present Milledgeville, Georgia, just below what was called the Rock Landing. In a letter, dated March 11, 1695, Gov. Laureano de Torres Ayala tells of an expedition consisting of 400 Indians and 7 Spaniards sent against the “Cauetta, Oconi, Cassista, and Tiquipache” in retaliation for attacks made upon the Spanish Indians. About 60 persons were captured in one of these towns, but the others were found abandoned.5 On the Lamhatty map they appear immediately west of a river which seems to be the Flint, but the topography of this map is not to be relied on. In the text accompanying, the name is given as “Opponys.”6 Almost all that is known of later Oconee history is contained in the following extract from Bartram:

Our encampment was fixed on the site of the old Ocone town, which, about sixty years ago, was evacuated by the Indians, who, finding their situation disagreeable from its vicinity to the white people, left it, moving upwards into the Nation or Upper Creeks,7 and there built a town; but that situation not suiting their roving disposition, they grew sickly and tired of it, and resolved to seek an habitation more agreeable to their minds. They all arose, directing their migration southeastward towards the seacoast; and in the course of their journey, observing the delightful appearance of the extensive plains of Alachua and the fertile hills environing it, they sat down and built a town on the banks of a spacious and beautiful lake, at a small distance from the plains, naming this new town Cuscowilla; this situation pleased them, the vast deserts, forests, lake, and savannas around affording abundant range of the best hunting ground for bear and deer, their favourite game. But although this situation was healthy and delightful to the utmost degree, affording them variety and plenty of every desirable thing in their estimation, yet troubles and afflictions found them out. This territory, to the promontory of Florida, was then claimed by the Tomocas, Utinas, Caloosas, Yamases, and other remnant tribes of the ancient Floridians, and the more Northern refugees, driven away by the Carolinians, now in alliance and under the protection of the Spaniards, who, assisting them, attacked the new settlement and for many years were very troublesome; but the Alachuas or Ocones being strengthened by other emigrants and fugitive bands from the Upper Creeks [i. e., the Creeks proper], with whom they were confederated, and who gradually established other towns in this low country, stretching a line of settlements across the isthmus, extending from the Alatamaha to the bay of Apalache; these uniting were at length able to face their enemies and even attack them in their own settlements; and in the end, with the assistance of the Upper Creeks, their uncles, vanquished their enemies and destroyed them, and then fell upon the Spanish settlements, which also they entirely broke up.8

We know that the removal of this tribe from the Oconee River took place, like so many other removals in the region, just after the Yamasee outbreak of 1715, and the movement into Florida about 1750.9 Their chief during most of this period was known to the whites as ”The Cowkeeper.” Although Bartram represents the tribe as having gone in a body, we know that part of them remained on the Chattahoochee much later, for they appear in the assignments to traders for 1761,10 and in Hawkins’s Sketch of 1799,11 while Bartram himself includes the town in his list as one of those on the Apalachicola or Chattahoochee River.12 The list of towns given in 1761 includes a big and a little Oconee town, the two having together 50 hunters. Their trader was William Frazer.10 Hawkins describes their town as follows:

“O-co-nee is six miles below Pā-lā-chooc-le, on the left bank of Chat-to-ho-che. It is a small town, the remains of the settlers of O-co-nee; they formerly lived just below the rock landing, and gave name to that river; they are increasing in industry, making fences, attending to stock, and have some level land moderately rich; they have a few hogs, cattle, and horses.“

They are not represented in the census of 1832, so we must suppose either that they had all gone to Florida by that time or that they had united with some other people. Bartram’s narrative gives, not merely the history of the Oconee, but a good account also of the beginnings of the Seminole as distinct from the Creeks. When we come to a discussion of Seminole History we shall find that the Oconee played a most important part in it, in fact that the history of the Seminole is to a considerable extent a continuation of the history of the Oconee.