The main characteristic, besides elaboration of burial practices, that distinguished the Early and Middle Woodland from Late Archaic traditions, was the gradual intensification of local and interregional exchange of exotic materials. For many years archeologists have regarded as “classic” those Middle Woodland sites with elaborate ceremonial earthworks that contained the burial mound graves of elite individuals buried with exotic mortuary gifts obtained through an extensive trade network covering most of the eastern United States. Because of the similarity of earthworks and burial goods found at widely scattered sites in the Southeast and the area north of the Ohio River, it was assumed that a cultural continuity-sometimes referred to as the Hopewellian Interaction Sphere-existed throughout much of the eastern United States.

Within the Ohio River drainage, the Early Woodland Adena culture, with its emphasis on elaborate mortuary customs, laid the foundations for the succeeding Hopewell (or Middle Woodland) culture.

Another way of interpreting the archeological manifestations of Middle Woodland burial mounds and elaborate burial goods obtained from distant sources may be as the result of reciprocal obligations and formal gift-giving between lineages or clans that controlled specific geographical territories. In this scenario, intensive exploitation of food or raw material resources in these areas, begun in the Archaic period, would lead to lineages or clans that controlled access to certain food or raw material resources important to, if indeed not necessary to, the survival of groups outside their territory.

Access to important food or raw material resources outside a clan’s territory would be insured by formalized trade between the leaders of clans of different territories. The role of the clan head in this exchange system would be recognized by the group erecting burial mounds and interring exotic goods obtained through long-distance trade with other clan heads. At the same time, the social identity of these cultural entities would be reinforced by regular burial ceremonies at earthworks where important clan leaders were buried. Such a cultural system would increase social and economic stability between the clans participating in reciprocal trade. It would also reinforce trends toward sedentary living and the promotion of agriculture, which, in turn, would provide a surplus of food and lead to an increase in population.

The Kolomoki Mound complex was the center of Swift Creek occupation during this period. The mounds remained active through its occupation with the Weeden Island culture of north central Florida.

Reciprocal trade, begun in the Early Woodland, would have served as a valuable cultural mechanism to spread the Hopewell (Middle Woodland) physical manifestations of earthworks and specialized burial artifacts throughout much of the eastern United States. As distinct territorial units entered into the trading sphere, their goods would be added to a pool of reciprocal trading items, and they would have access to goods unavailable in their own territory. At least some nonorganic trade items can be identified from the study of the burial mounds of the Middle Woodland. To this trade, the Middle Woodland territories of the Southeast appear to have provided mica, quartz crystals, and chlorite from the Carolinas, and a variety of marine shells, as well as shark and alligator teeth, from the Florida Gulf Coast. In exchange, the Middle Woodland clans of the Southeast received galena from Missouri, flint from Illinois, grizzly bear teeth, obsidian and chalcedony from the Rockies, and copper from the Great Lakes. Standardization of style for the finished artifacts used in this trade may be attributed to a relatively small number of clan leaders controlling the exchange system and developing their own symbolic artifact language of what trade goods constituted a reciprocal exchange between clans.

This winged bannerstone is a type usually found in the Midwestern states. Trade and interaction brought this unusual artifact to the Chattahoochee River area.

Most of the western and central Kentucky and western Tennessee Woodland cultures appear to have participated fully in the Ohio River Valley Early and Middle Woodland trading network. These cultures exhibited common burial practices and earthwork construction from the very start. Excavations in Kentucky have recovered Havana-like or Hopewell-decorated ceramics and Copena and McFarland projectile points. Burial offerings included gorgets, stone or clay tablets, tubular and biconical pipes, galena, mica crescents, copper bracelets, and marginella beads.

In western North Carolina, the early Middle Woodland Pigeon phase (300 B.C. to A.D. 200), noted for it crushed-quartz-tempered ceramics, was replaced by the Connestee phase (A.D. 200 to 600), which produced thin sand-tempered ware. Pigeon and Connestee components are present at Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The Connestee culture apparently was a major source of mica, quartz crystal, steatite, and chlorite schists for the Ohio Hopewell trade network. These were traded out for Tennessee cherts, Appalachian quartz crystals, Flint Ridge chalcedony of Ohio, and Chillico ceramics. Connestee ceramics have been found at Georgia, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee sites.

Prior to about A.D. 1 most of the Deep South continued a Late Archaic style of seasonal rounds of hunting and gathering. This was supplemented by geographic specializations- such as riverine and coastal zone shellfish exploitation-and the planting and harvesting of some native plants. The Early Woodland and early Middle Woodland cultures of the Deep South are differentiated by a variety of regional ceramic styles. There appears to be limited direct contact between these cultures and Hopewell influences to the north. For example, Louisiana appears to have had contact with the Illinois River Hopewell during the Marksville times of the Middle Woodland. At the end of the Late Gulf Formational (500 to 100 b.c.), the interior area of Mississippi and Alabama adopted sand-tempered ceramics (Alexander) introduced from the north. There appeared to be some linkage between Middle Woodland cultures to the north through trade in locally available Tallahatta quartzite and Fort Payne and Camden chert. However, the subsistence activity of this culture was essentially Late Archaic in nature.

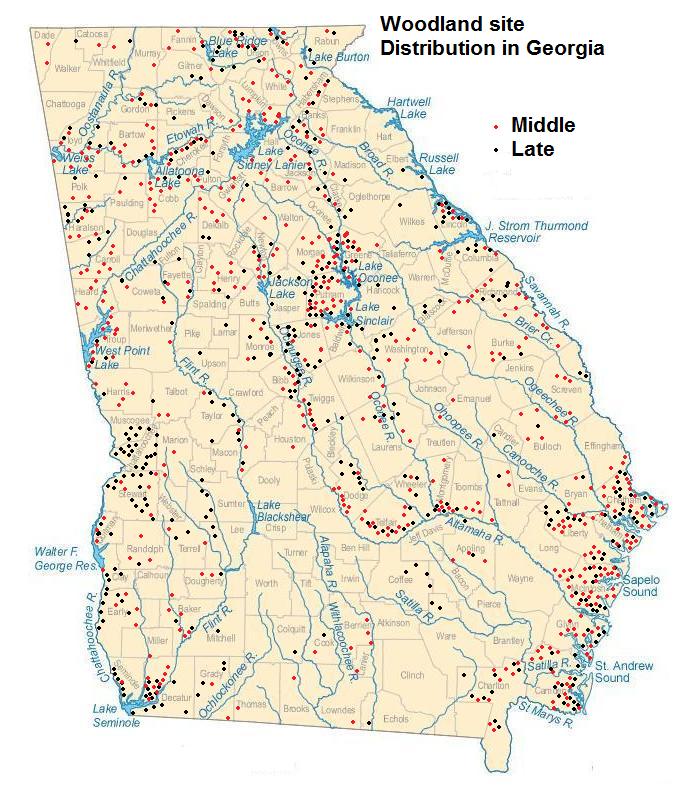

In northern Georgia, the predominant Middle Woodland ceramics are the Cartersville and Swift Creek series after about 300 b.c. The incorporation of western Georgia into the Hopewellian Interaction Sphere of Trade and the appearance of burial mounds only occurred from about A.D. 100 to 450. The exchange of materials associated with Hopewellian ceremonialism was restricted to western Georgia and did not appear to have spread, at this time, into eastern Georgia or South Carolina.

The Florida Lithic Dagger was a mortuary blade often interred after being ceremonially broken. Many of these blades were recovered with Deptford ceramics.

The Middle Woodland accouterments of burial mounds arrived later in the Deep South. In central Mississippi, the Miller culture (100 b.c. to A.D. 650) saw the introduction of burial mound ceremonialism, sand-tempered ceramics, and interregional trade from the Crab Orchard culture of western Kentucky and Tennessee and the Illinois Valley Hopewell. This area also received influence from the Marksville culture of the lower Mississippi River Valley. Some of the larger Miller burial mounds have produced Marksville pottery, galena, and copper earspools. Subsistence was based primarily on intensive seasonal hunting and gathering.

From the Early through the Middle Woodland periods, the extensive, low-lying coastal environment of the South Atlantic coast, stretching from North Carolina to northern Florida, was used by numerous Deptford hunter-gatherer bands who lived seasonally within a variety of ecosystems and took advantage of seasonally available foods.

Along the Gulf Coast, the Deptford culture continued the transhumant (or seasonal) existence throughout the Middle Woodland. Settlements in this geographical area lacked permanence of occupation, although the cultures here participated in the Hopewellian trading network to a limited extent and constructed numerous low sand burial mounds. These sand burial mounds along coastal Georgia and Florida (noted at Canaveral National Seashore and Cumberland Island National Seashore, for instance), as well as in the Carolinas, are believed to represent local lineage burial grounds rather than the resting place of an elite individual.

In northwest Florida, the Early Woodland Deptford culture evolved in place to become the Santa Rosa/Swift Creek culture. Trade items recovered from burial mounds include copper panpipes, ear ornaments, stone plummets, and stone gorgets. These show this area’s incorporation within the Hopewellian Interaction Sphere by about A.D. 100.

The Marksville culture (A.D. 1 to 400) existed throughout the lower Mississippi River Valley and extended eastward along the Gulf Coast to the Mobile Bay area, an area that now incorporates Gulf Islands National Seashore. Marksville culture showed marked similarity with the contemporary Hopewell culture of the Illinois River Valley, particularly in the emphasis on earthworks containing burial mounds and the interring of exotic trade goods with the dead. Among the exotic trade items recovered by excavations in both areas were copper panpipes, earspools, bracelets and beads, stone platform pipes, mica figurines, ceramic figures, galena, marine shells, freshwater pearls, and green stone celts. The quantities of exotic trade material found in Marksville sites, however, indicate only minimal contact between the two areas.

Marksville sites tend to be located on major waterways. Subsistence consisted of intensive hunting and gathering, with some suggestion of maize horticulture. Although the current view is that there was no economically important horticulture during Marksville times, it appears the Marksville culture represents an in-place cultural evolution from the Archaic through the Woodland periods with selective adoption and reinterpretation of Hopewellian ideas.

In the interior of the Deep South during the Middle Woodland period, one sees the permanent occupation of small- or medium-sized villages along major rivers (Ocmulgee National Monument, for example), placing these settlements in the forefront of the expanding Hopewellian trading sphere along water courses. Between A.D. 1 and 450, these interior sites joined the Middle Woodland trading sphere as shown by the construction of hundreds of low oval mounds, many containing traded material from the Ohio Valley or the southeastern seacoast.

The large shell mounds made up of millions of shells and shell tools is a clear indication of the minimal influence the Mississippian period developments had on the St. Johns culture living along the rivers of northeastern Florida.

The rest of the continental southeast was only marginally affiliated with the Hopewellian Interaction Sphere. The St. Johns culture area of east and central Florida developed its own unique culture between 1200 B.C. and A.D. 1565. This was exhibited by a number of sites in Canaveral National Seashore, Castillo De San Marcos National Monument, Fort Matanzas National Monument, and Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve. The St. Johns culture evolved in place from the Late Archaic Orange culture. Subsistence showed little in the way of agriculture, with the majority of food coming from seasonal plant food collecting, hunting, fishing, and shellfish gathering. This basically Archaic subsistence economy was able to support prehistoric Native Americans for 2,000 years until contact with Europeans. The St. Johns culture was largely unaffected by Hopewell influences, although they did construct sand burial mounds, a few containing Hopewellian-like grave goods.

The Manasota culture (500 B.C. to A.D. 800) of the Central Peninsular Gulf Coast of Florida, like the St. Johns culture, subsisted by plant-food collecting, fishing, hunting and shellfish gathering. The Manasota culture appears, as well, to have evolved in place from the local Late Archaic culture. At the beginning of the Manasota culture (500 b.c.), burials were interred in the shell midden of the villages. By 400 b.c., however, sand mounds for the interment of the dead were constructed. Later still (around A.D. 600), elaborate imported burial gifts were interred with the dead. Finally, the Manasota culture began to construct simple burial mounds that contained Weeden Island pottery (A.D. 800).

The Lake Okeechobee/Kissimmee River basin of south central Florida saw the construction of major earthworks between 1000 b.c. and A.D. 200 for horticultural purposes rather than as true burial mounds. By A.D. 200, this area was incorporated in the Glades culture area, which today contains Big Cypress National Preserve, Biscayne National Park, and Everglades National Park.

Matacoombee Incised pottery from south Florida.

Beginning around A.D. 1, the Glades culture of south and southeast Florida represents a transitional culture from the Archaic. By A.D. 800, distinctive Glades pottery, shell tools, and bone tools appeared, remaining essentially un-changed until contact with Europeans in the sixteenth century.

The Middle Woodland of the North Carolina coastal plain is represented by two cultures, the Mount Pleasant culture in the northern part of the state and the Cape Fear culture in the southern part. Both date from about 300 b.c. to A.D. 800. Ceramics for the Mount Pleasant culture are sand and grit tempered with fabric-impressed or cord-marked surface finish. Shell-tempered ceramics from the Mid-Atlantic area also occur.

Although the Cape Fear and Mount Pleasant culture ceramics are similar, the Cape Fear culture exhibits an extensive distribution of low sand burial mounds that represent an influence out of South Carolina. Many burials contain gorgets, arrow points, conch shells, and platform pipes. This area appeared to have had only limited connection with the Hopewell Interaction Sphere. A few Mount Pleasant sherds have been recovered from Fort Raleigh National Historic Site.

Projectile points and blades that dominate Middle Woodland sites include many that were introduced during the Early Woodland as well as Florida’s Ocala, Copena Classic and Triangular points, Florida’s Swift Creek Point (Named at the 8 LE 148 site in Leon County, Florida), Camp Creek, Candy Creek, Yadkin, Tallahassee, Eared Yadkin, Greenville, Broward (that some would argue is a large Baker’s Creek point), and the Gadsden (a form of Broward point along with Florida’s Taylor point).